We don’t see Crockett and Tubbs in the immersive, neon-soaked HBO Max series “Tokyo Vice,” but the pilot episode is directed by the great Michael Mann, who created “Miami Vice” and has helmed such classic thrillers as “Thief,” “Collateral” and “Heat.” It’s one of the best hours of television so far this year—and the good news is “Tokyo Vice” retains that high level of quality, at least through the five episodes of the series made available for review.

With Ansel Elgort delivering a performance that ranks with “Baby Driver” as his career best, playing an American investigative journalist who takes a deep and dangerous dive into the world of the Yakuza organized crime syndicate, and a brilliant supporting cast including the legendary Ken Watanabe, Rinko Kikuchi, Sho Kasamatsu and Rachel Keller, “Tokyo Vice” is an electric and pulse-pounding series. Each taut, kinetic, beautifully photographed episode is filled with indelible images and scenes from the Tokyo of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when various factions of the Japanese mob operated with near impunity from law enforcement, raking in protection fees from small businesses, running nightclubs, loan sharking and even carrying out executions without fear of exposure from the media or criminal prosecution.

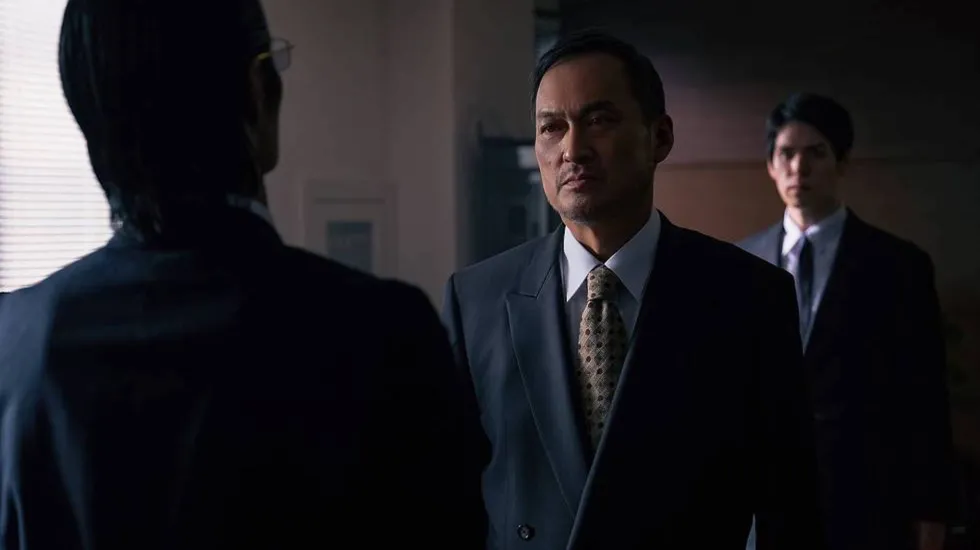

As outlined in “Tokyo Vice,” which is inspired by Jake Adelstein’s memoir of the same name, there’s a serious disruption to the status quo when Adelstein (Elgort) teams up with the incorruptible police detective Hiroto Katagiri (Watanabe) to shine a harsh spotlight on the nefarious practices of the Yakuza. We’ve seen this type of crusader-vs.-criminals story play out in countless TV productions and in dozens of movies, but it feels fresh and cutting-edge here.

Premieres with three episodes Thursday on HBO Max, followed by two new episodes each Thursday through April 28.

“Tokyo Vice” employs the familiar technique of starting near the end with a tense confrontation and then taking us back to the beginning of the story. In the opening scene, Jake and Katagiri meet with some high-ranking members of the Yakuza in a private lounge at a Tokyo nightclub, where Jake is told, “We know what you’re investigating. We want you to stop. … Publish it [and] there’s nowhere you can hide. We’ll ‘visit’ your whole family.”

Bone-chilling stuff—and then we’re plunged back two years, to 1999, with Jake as the classic Fish Out of Water, i.e., he’s an American from Missouri who is absorbing the Japanese culture, including taking Aikido classes and studying the language to the point where he’s fluent, all in the service of trying to become the first foreigner to work for the largest newspaper not only in Japan but in all the world, with a circulation of some 12 million. (At his interview, Jake is told, “You’re Jewish … many here believe Jews control the world economy.” His response: “If we did, do you think I’d be happy with what you’d pay me?”)

As the dialogue toggles between English and Japanese, we can see how Jake reaches a certain level of acceptance in the newsroom and on the streets—but is often reminded he’ll always be considered an outsider on some level. (Elgort reportedly took an intense crash course in Japanese and seems to hold his own.)

Jake is cocky and sets out to make an immediate splash, but when he bungles his first few stories, his tough but fair senior reporter and supervisor, Eimi Maruyama (Rinko Kikuchi in a resonant performance), busts him down to the scrapbooking beat (cutting and pasting clippings) and tells him he’ll be out of a job if he doesn’t come up with something substantial soon. Through a combination of tireless work and being in the right place at the right time, Jake gradually gains the trust of Katagiri as he investigates a series of suicides in Tokyo, all committed by individuals who are in deep debt to Yakuza-controlled loan sharks and have been pressured to kill themselves. (The loan papers signed by these victims were actually life insurance policies—with the mob as the beneficiaries.)

A number of intriguing subplots are expertly woven into the fabric of that main storyline. The first time we see Rachel Keller’s Samantha, a hostess at a club in the red-light Kabukichō District, she’s singing karaoke in English and Japanese to “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” and we can immediately see why she’s a captivating presence who catches the attention of Jake as well as Sho Kasamatsu’s Sato, a young and rising presence in the Chihara-kai organized crime outfit. The dynamic between Jake and Sato is fascinating; they kinda like and respect each other but definitely don’t trust one another. (As for Samantha: At first her storyline isn’t nearly as compelling as the investigative journalism and police work thread, but when we learn more about her back story, we’re equally invested in her story.)

Filmed on location in Tokyo, this series captures the corrupt underbelly of the city, from the glitzy, mob-run nightclubs to the strict rituals of the warring factions of the Yakuza to some heart-stopping moments of violence and tragedy, e.g., when a man soaks himself with gasoline and sets himself on fire in front of a horrified crowd. Early on in the story, Jake tells Katagiri, “I want to learn how this city … beneath the surface, how it really works.” Thanks to the crisp writing, powerful acting and gorgeously haunting visuals, “Tokyo Vice” always has us feeling as if we’re on a ride-along with Jake through the entire harrowing and sometimes exhilarating adventure.