Skating rinks, funfairs and booths serving hot food and drink spring up across many cities in December. But these festivities aren’t a modern phenomenon – they’re rooted in the frost fairs of our past, held on London’s River Thames from the 1600s until 1814.

Frost fairs are associated with the “little ice age” – the long periods of bitter European winters between the 14th and 19th centuries. Although climatic conditions enabled the ice to freeze in a certain way, they weren’t the only part of the story.

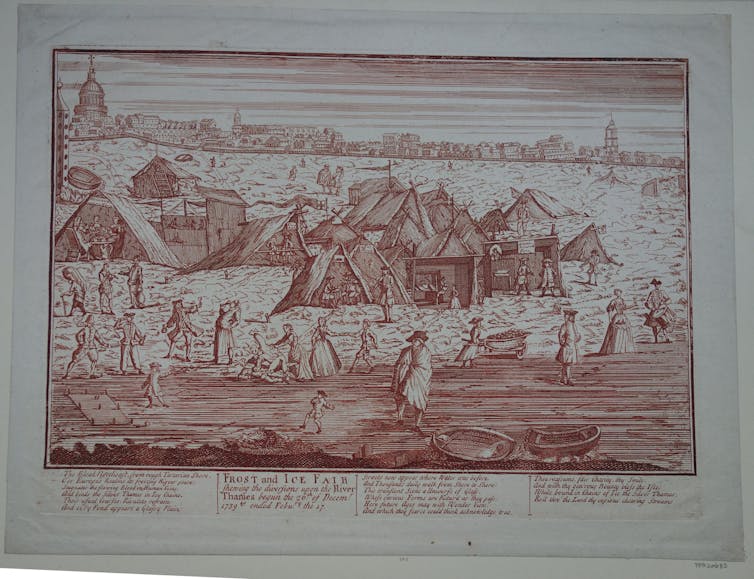

Frost fairs presented economic opportunities during times of hardship. Tented encampments sprung up across the River Thames to house the city’s imperative – trade.

A printed description of the fair of 1683 noted that visitors could sit by a charcoal fire with “a dish of Coffee, Chocalet, or Tea”, suggesting that they enjoyed these hot beverages just as much as we do today.

Makers and sellers of all manner of goods set up stall on the ice, including weavers with their looms and sellers of lottery tickets and toys.

Toy sellers’ goods were not meant for children – they sold luxurious miniature objects to be enjoyed by adults. One such is a tiny glass mug less than six centimetres tall which is now displayed at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. This is a souvenir not only of drinking ale in a tavern on the ice, but also celebrating the recently established Southwark glass industry. The industry’s smoking chimneys were Thames-side landmarks.

Entertainment worthy of royalty

Royal endorsement was important for the frost fairs’ success.

The names of Charles II and the royal family were recorded on a souvenir card printed during the final days of the 1683 fair. The list of names includes Hans in Kelder (Jack-in-the-Box) – the unborn child of the pregnant princess (later Queen) Anne.

However, the fairs were not just about royal visitors. Everyone and anyone seemed to want to link their name to the ice.

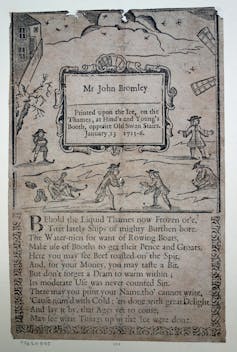

In an era before the selfie, printers’ booths produced cards with a person’s name, sometimes attached to a view of the fair or a portrait of a well known figure.

The crucial function of this card was verifying the location. They featured messages such as “Printed upon the ice on the Thames”, followed by the day, month and year.

Picturing the icebound river

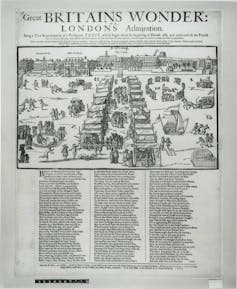

Painters and printers produced views of the fairs, often taken from the bank or from a midway point in the river looking towards Old London Bridge.

Print titles such as Great Britain’s Wonder reflected contemporary fascination with the transformation of the river.

Some activities, such as bear baiting, are repugnant to us today. Others have endured, including football – which was popular, even though players risked “broken shins”.

Some sports specific to the ice likely originated elsewhere, reflecting London’s diverse population. These included skating, which was associated with “Dutch-men” who “in their skates did swiftly slide”.

Prints also showed sledges loaded with wood, corn and coal being hauled across the ice – supplies which hugely increased in price during frost fairs.

What these artworks rarely show are the dangers of the ice and the economic hardship it brought, particularly to those who could not afford the inflated prices of food and fuel as a result of the freeze.

Danger on the ice

Frost Fairs also created opportunities for unregulated behaviour.

One print of the 1739 fair warned that it was frequented by “Gamesters, and Thieves” while another showed a young woman trying to break up a fight between two men.

In 1684 a ballad was written about the “merry Pranks plaid on the River Thames during the great Frost”. It warned of being there under “moonshine”, when “slippery things have bin done on the ice”.

This is likely a reference to unregulated sexual behaviour and the presence of pickpockets.

The evolution of the frost fair

It wasn’t just warmer winters that brought an end to the fairs. The demolition and rebuilding of London Bridge meant the River Thames no longer trapped the ice and tide.

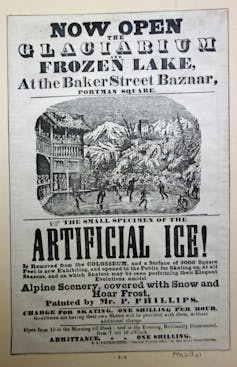

By the 1840s, new technologies were producing artificial ice. A “glaciarium” opened in London in 1843 and was pictured as an altogether more refined event, with a viewing gallery and Alpine inspired scenery around the rink.

Winter wonderlands are nothing new. Today’s cities are adapting the frost fairs of old to recreate the experience of being in a frozen environment in winter – a reality which is becoming increasingly rare.

Clare Taylor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.