Tiny photosynthetic microbes could be secretly thriving on Mars — hiding inside small bubbles of liquid water in the thin layers of dusty ice that litter the Red Planet's surface, a new NASA-led study reveals.

Researchers believe the icy patches could be among the most promising targets in the hunt for extraterrestrial life within our solar system — and plan to recreate them in the laboratory on Earth to test the predictions.

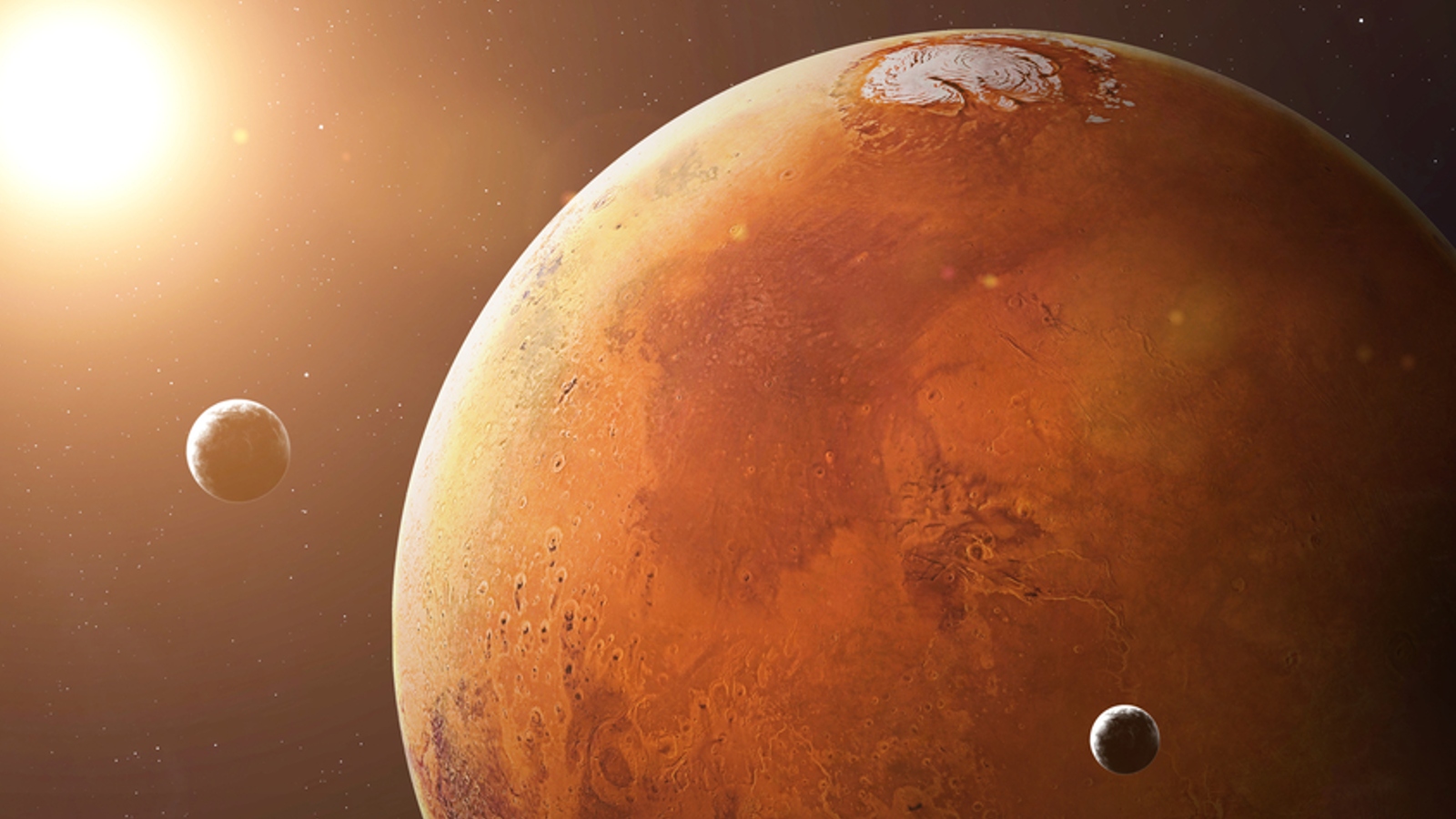

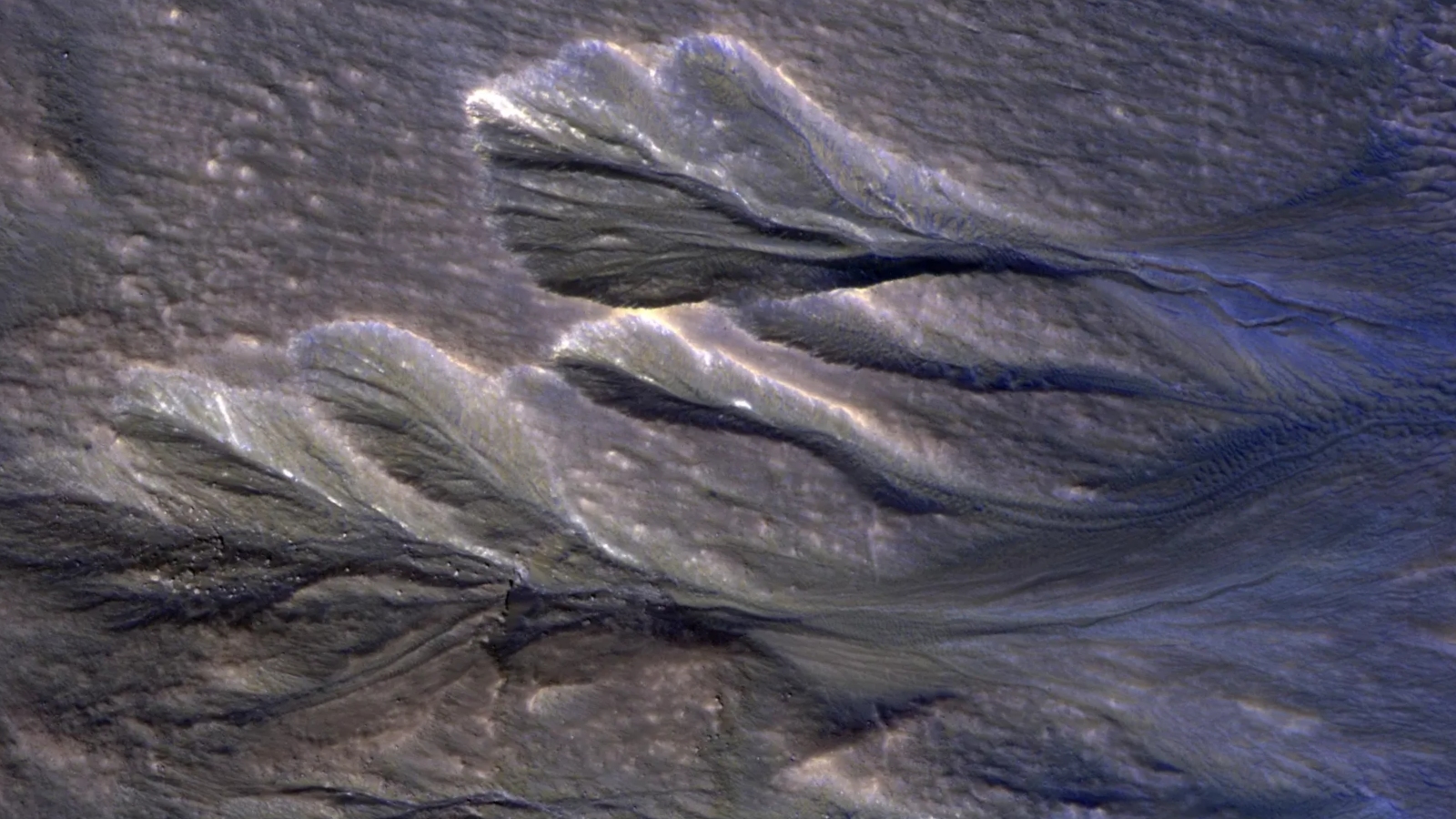

Mars is a surprisingly icy world: The planet has frozen sand dunes covering its north pole, giant slabs of carbon dioxide ice above its south pole and massive chunks of frozen water buried near its equator. However, it also has smaller sub-zero features, including patches of dusty water ice left behind by ancient snow drifts that clung to specific spots on the planet's surface, such as the bottoms of gullies and ravines.

In a new study, published Oct. 17 in the journal Communications Earth and Environment, researchers created computer models to simulate the conditions within this dusty surface ice and found that it could contain tiny bubbles of meltwater, which can act as miniature "habitable zones" for microbial life left over from Mars' watery past.

The researchers proposed that the hidden cavities could provide single-celled organisms with three key requirements for photosynthesis: liquid water, carbon dioxide gas from Mars' wispy atmosphere and sunlight, which shines through the thin ice above. The ice could also theoretically shelter microbes from potentially deadly solar radiation and cosmic rays, which bombard Mars' surface because of the planet's lack of magnetic shielding.

Related: NASA may have unknowingly found and killed alien life on Mars 50 years ago, scientist claims

It would be easy for future astronauts and colonists to reach the dusty ice and find these bubbles, which makes them an even more appealing place to look for extraterrestrial life, the researchers wrote. "If we're trying to find life anywhere in the universe today, Martian ice exposures are probably one of the most accessible places we should be looking," study lead author Aditya Khuller, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement.

According to the researchers, grains of dark-colored dust buried beneath thin layers of surface ice can be heated by sunlight shining through the ice, creating pockets of space that fill up with melting water. This is perhaps one of the only places where liquid water could readily form on Mars because ice normally sublimates — or turns directly into gas — when it gets heated, the researchers wrote.

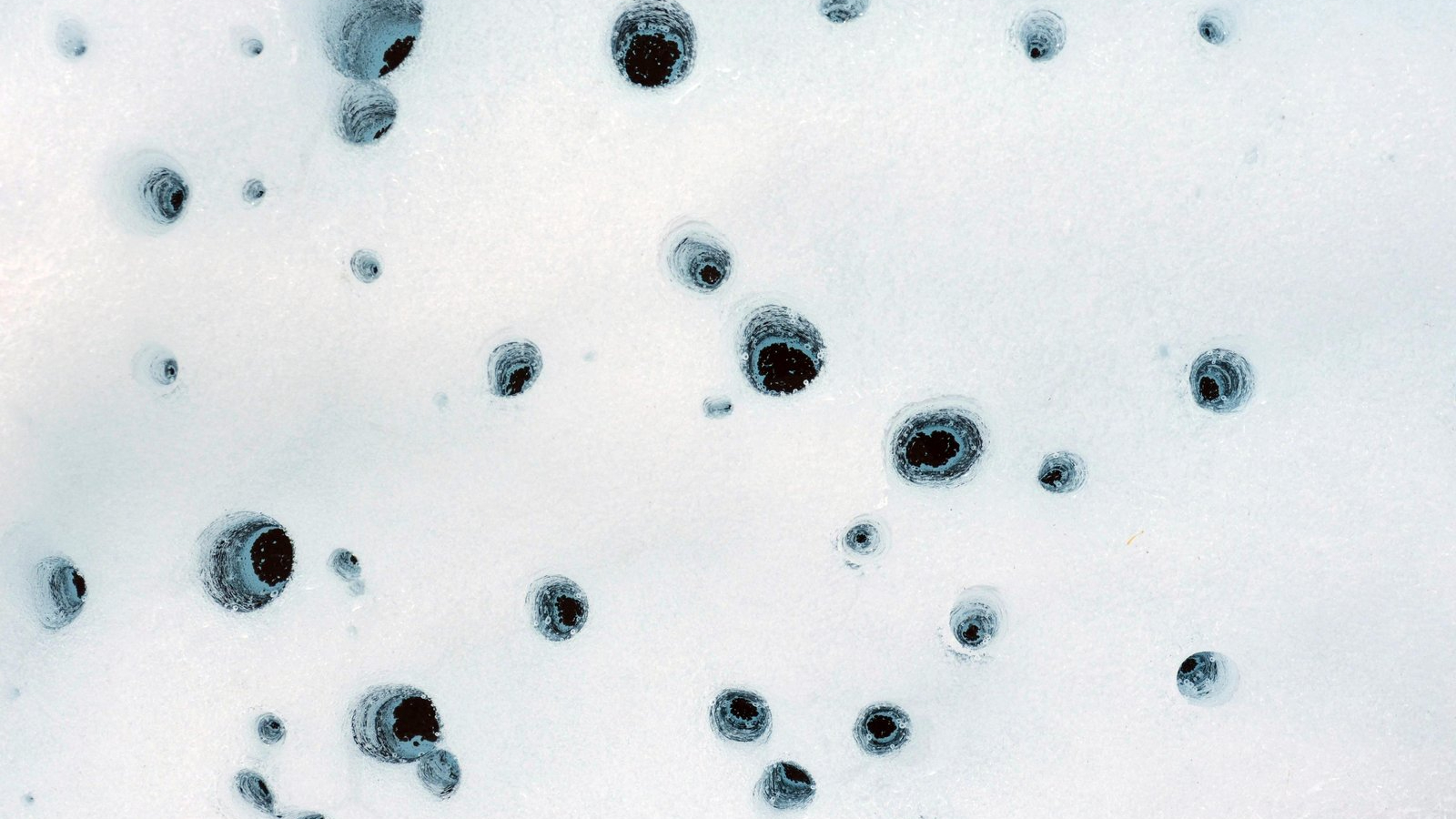

A similar process happens on our planet: When dust gets trapped within snow, glaciers and ice sheets, it creates spaces known as cryoconite holes, which often contain liquid water — and sometimes life.

"This is a common phenomenon on Earth," study co-author Phil Christensen, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University, said in the statement. "Dense snow and ice can melt from the inside out, letting in sunlight that warms it like a greenhouse, rather than melting from the top down."

A wide variety of photosynthetic organisms live in cryoconite holes, such as algae, fungi and cyanobacteria. During winter, when temperatures drop and the holes refreeze, these lifeforms enter into a hibernation-like stasis where they effectively pause all key functions until the holes reform in summer, the researchers wrote. Any potential Martian microbes may do something similar, they added.

Based on the new computer models, researchers think that the meltwater bubbles could form in ice up to 9 feet (3 meters) deep, as long as the dust content is low (less than 1%). However, this is only likely to happen at latitudes between 30 degrees and 60 degrees. Any closer to the planet's poles, and the ice will likely be too cold for bubbles to form.

The team plans to continue studying this proposed phenomenon, using additional computer models and Earth-based experiments to learn more about how and where it might happen.

"I am working with a team of scientists to develop improved simulations of if, where, and when dusty ice could be melting on Mars today," Khuller told Live Science's sister site Space.com. "Additionally, we are recreating some of these dusty ice scenarios in a lab setting to examine them in more detail."