Closing last month, this year WA Museum Boola Bardip in Perth was host to a major exhibition Discovering Ancient Egypt.

The Australian Museum’s “once-in-a-lifetime” Ramses & The Gold of the Pharaohs exhibition featuring 181 objects from ancient Egypt opened last week in Sydney.

Just four weeks after that exhibition shuts, the 2024 “winter masterpieces” exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne will be Pharaoh, featuring 500 objects in the largest international loan ever from the British Museum.

Why is there such an intense fascination with a civilisation so far removed from our time and place?

Centuries of Egyptomania

Few historical cultures seem to have such a hold over the minds of the general public.

Awe-inspiring temples, elaborate mummification rituals, beliefs in afterlife, and contributions to science, technology, engineering and medicine left an indelible mark on the course of human progress.

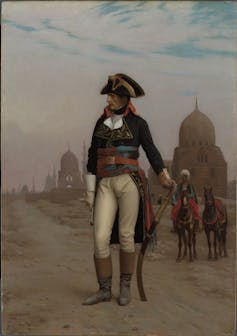

“Egyptomania”, a term coined to describe the West’s fascination with Egypt, can be traced back to Napoleon’s expedition in the late 18th century. Scientific discoveries and illustrations from that expedition fuelled worldwide curiosity about the secrets of this ancient land.

A key figure of the Egyptomania was Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1823), an Italian explorer and strongman (and con-man) whose daring adventures and discoveries – including removal of colossal Egyptian statues – added fuel to the fire.

This cultural phenomenon influenced fashion and design. Egyptian motifs, such as lotus flowers, scarabs and sphinxes became popular decorative elements in clothing, jewellery and home decor during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Agatha Christie (who was married to archaeologist Max Mallowan and spent many years working on excavations in the Middle East) sent her famous detective Hercule Poirot into the world of mummies and pharaohs in Death on the Nile and set Death Comes as the End on the Western Bank of Thebes.

Ancient Egypt’s grip on our collective consciousness manifests throughout popular culture. Films such as The Mummy and Cleopatra, games such as Assassin’s Creed Origins and popular cartoon TV series Tutenstein blend historical facts with creative storytelling, perpetuating the mystique and wonder of this lost civilisation.

Ancient Egypt is a staple in schools. For many Australians, their first introduction to a world beyond their immediate surroundings often comes in the form of ancient Egyptian history in the national curriculum for year 7.

This portal to history and foreign cultures opened in childhood often results in lifelong fascination. You might ask: how much Egypt can Australians take? It seems the answer is “a lot”.

Read more: More than a story of treasures: revisiting Tutankhamun's tomb 100 years after its discovery

A long line of exhibitions

These latest exhibitions follow a long, near continuous, list of Egyptian exhibitions in Australia.

In 2007, the National Gallery of Australia showcased Egyptian Antiquities from the Louvre: Journey to the Afterlife.

Tutankhamen And The Golden Age Of The Pharaohs was at the Melbourne Museum in 2011. The Western Australian Museum hosted Secrets of the Afterlife: Magic, Mummies and Immortality in Ancient Egypt in 2013. Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives was at Sydney’s Powerhouse in 2016.

In 2012, the Queensland Museum hosted items from the British Museum in Mummy: Secrets of the Tomb. The same museum hosted British Museum artefacts again in 2018 in Egyptian Mummies: Exploring Ancient Lives. In between, the Queensland University Museum hosted Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs from 2016–18.

From an impressive gallery in Chau Chak Wing Museum in Sydney to the small – and in need of a serious update – gallery in the South Australian Museum, each state also proudly displays its own permanent collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts.

Despite this extensive exhibition history, Australia’s interest in ancient Egypt seems to show no signs of waning.

Shifting Egyptology

The new exhibition in Sydney gives a window into the life and accomplishments of Ramses II who ruled Egypt for 67 years.

The National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition will aim to deepen visitors’ understanding of ancient Egyptian culture, allowing them to see beyond the opulence.

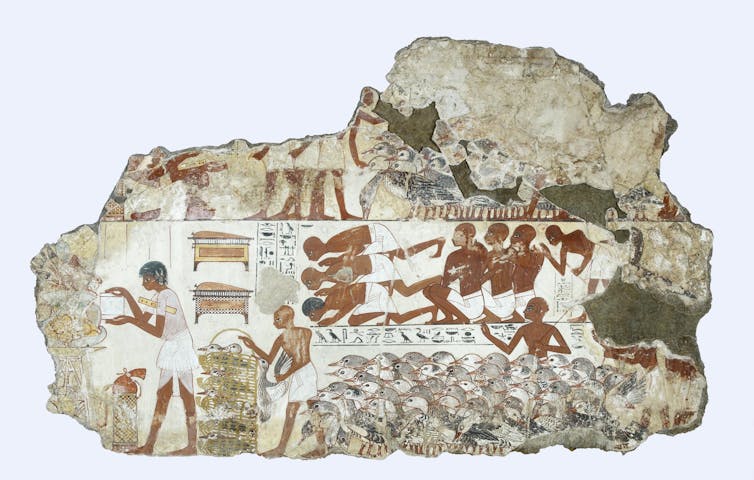

This is part of a broader shift in Egyptology, archaeology and history towards emphasising understanding of the lives of everyday people.

For a long time, Egyptology was centred on grand monuments, temples, tombs, pharaohs and the elite. We now recognise that to understand a civilisation we need to also explore the lives, activities and contributions of ordinary people.

But these major exhibitions coincide with rising debates about the provenance and repatriation of artefacts. A Tutankhamen exhibition which toured the world just before the COVID pandemic and which was scheduled to appear in Sydney has, amid some controversy, finally settled back at home, in the Grand Museum in Cairo, Egypt, where it will – hopefully – remain forever.

Repatriation of artefacts is a sensitive issue that has been gaining momentum in recent years and questions are being raised, even more loudly now, whether institutions such as the British Museum should even possess such artefacts.

Zahi Hawass, former minister of antiquities for Egypt, has called for repatriation of stolen heritage and accused western museums of continuing imperialistic practice by purchasing new artefacts and refusing to return them to their country of origin. Some large travelling exhibitions are already moving away from displaying these artefacts towards immersive digital experiences with great examples in Lisbon, Vienna and Cairo.

For now in Australia, though, it is not just artefacts and treasures that will be on display. It is a celebration of human spirit, ingenuity and quest for knowledge. The sands of time have failed to bury our fascination in ancient Egypt.

Anna M. Kotarba-Morley receives funding from Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.