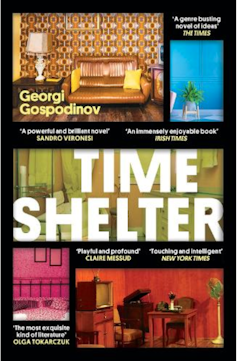

A philosophical exploration of memory and nostalgia, about forgetting and trying to hold on to our past and make sense of our present and future, Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter is a worthy winner of this year’s International Booker prize.

If ours is an age of privation, this expansive novel symbolises opulence: of ideas, meanings, utopian aspirations and the bizarre brilliance of the human mind. The author convenes memory, nostalgia and history together with the individual and the nation, to chart a narrative arc over the territories of remembrance and oblivion. Above all, it is a book about time, in its fragments and in its perpetuity.

As with so many prize-winning novels, Time Shelter conjures up episodes of human history to make us ponder what we have gone through and what we are living with. It is a book that forces the reader to go slow, given the sheer amount of stimulation for the senses and ideas that it has to offer.

The author’s use of history is masterful and central to the narrative. The novel is a great experiment in terms of narrative style, structure and ideas, and can only come from a literary culture that is not bogged down by canons and rules.

Gospodinov is an acclaimed poet, playwright and writer both in Bulgaria and in Europe, and is the recipient of several national and international literary prizes. The work is beautifully translated by Angela Rodel, who shares in the prize.

Judges’ chair Leila Slimani called Time Shelter – the first Bulgarian work to win the prize – a “brilliant novel” describing it:

A profound work that deals with a very contemporary question: what happens to us when our memories disappear? … Time Shelter is a great novel about Europe, a continent in need of a future, where the past is reinvented and nostalgia is a poison.

The land of Time Shelter is inhabited by just two main characters: the unnamed narrator and their friend Gaustine, a geriatric time-travelling psychiatrist who darts in and out of the narrative, at times claiming his space with profound quotes and observations.

In an interview, Gospodinov said that he, the narrator and Gaustine flow into one another, making him feel like he is being invented by his character Gaustine. With such unstable narrative entities, what readers are left with are voices that merge and lapse, but endure.

The structure of the novel itself gives the feeling of slowly losing one’s grip over time and narrative as the story becomes increasingly fragmented. The author clarifies that since it is a novel about Alzheimer’s, the collapsing narrative gives the idea of the characters and the narrator losing their memory, and the fading effect is transmitted to the reader.

The past is contagious

The narrator and Gaustine create what they call a “clinic for the past” that offers a hopeful treatment for people with Alzheimer’s. Each floor carefully recreates a period from the patient’s past, transporting them back to a more comforting time when life was good.

The “discreet monster of the past” is brought back with a “therapeutic aim” in these rooms. The nostalgia rooms become more and more important and effective in providing the patients with a slice of familiarity and memory.

Gospodinov explores the different aspects of remembering. While preserved memories can bring solace for some, there are characters like Mrs Sh., whose shower phobia is traced back to her experiences of the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Memories that she has forcefully repressed surface overwhelmingly in the phase of dementia and become a part of her “inescapable reality”. Some memories of inhumanity simply do not fade away but lurk in a corner ready to pounce in a moment of weakness.

In this onslaught of memories, nostalgia is inescapable. And it is in nostalgia that the personal and the historical, the individual and the nation, find refuge.

What starts with Alzheimer’s patients recreating their “happy times”, re-enacting their histories and escaping into the past begins to gain momentum. As the solace provided by these rooms becomes apparent, healthy people without memory loss are increasingly drawn to the clinic as a way of escaping the troubled present.

The unsustainability of nostalgia

In Time Shelter’s world, each European country holds a referendum about recreating history and slipping back into better times, transforming themselves into nostalgia nations with temporal borders. With tongue-in-cheek humour, the UK does not take part due to Brexit.

This is a modern-day utopia and dystopia rolled into one. Anarchy creeps in even amid the contentment of collective nostalgia, and “the world has become a chaotic open-air clinic of the past, as if the walls had fallen away”.

Gospodinov reveals the unsustainability of nostalgia, even though it can be a source of comfort, and the danger of dwelling on our histories. What starts off as therapeutic ultimately brings chaos and fragmentation.

The art of good storytelling demands fresh perspectives, reinvention, and yet a close tie to one’s narrative heritage. Time Shelter is all of that and much more. Gospodinov’s deft brewing of European history, utopian ideals and the devastating reality of neurological disorders will continue the conversation on human fragility well beyond the pages of this book.

Sukla Chatterjee does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.