This post on the Tibetan Uprising is the second in a series. It describes the Chinese invasion of 1949-50, including the Tibetan government's failure to fight when it could have won. Later, when the communists announced gun registration, the Tibetans knew that confiscation and subjugation were next. So they revolted.

Previous Post 1 covers Tibet before the 1949 Chinese invasion, including the Tibetan government's refusal to heed the 1932 warning of the Dalai Lama to strengthen national defense against the "'Red' ideology".

These posts are excerpted from my coauthored law school textbook and treatise Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights, and Policy (3d ed. 2021, Aspen Publishers). Eight of the book's 23 chapters are available for free on the worldwide web, including Chapter 19, Comparative Law, where Tibet is pages 1885-1916. In this post, I provide citations for direct quotes. Other citations are available in the online book chapter.

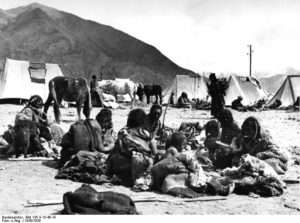

The Communist Occupation of Eastern Tibet

In February 1949, when the communists were well on their way to winning the Chinese civil war, Mao explained his Tibet policy to a leading Soviet Union official. Tibet, said Mao, would be easy to solve, but could not be rushed. "First transportation is poor in the region, making it difficult to move in large numbers of troops and keep them supplied. Second, it takes longer to solve the ethnic questions in regions where religion holds sway. . . ." Jianglin Li, Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959 at 23 (2016).

One reason Tibet did not have much of a road network was that the government opposed the use of motor vehicles, which were seen "as modern and anti-Tibetan." Kenneth Knaus, Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival 10 (1999). The traditional lack of good roads ultimately helped the resistance. If Tibetans had grown accustomed to motor transport, they would have been reliant on imported fuel, and the Chinese could easily have cut off resistance access to fueling stations. Because the Tibetan resistance used horses rather than motor vehicles, their transport has ready access to local fuel derived from solar power—namely grass.

In the summer of 1949, the communist army advanced into northeastern Tibet (Amdo province). "Tibetan resistance was immediately aroused." Warren W. Smith, "The Nationalities Policy of the Chinese Communist Party and the Socialist Transformation of Tibet," in Resistance and Reform in Tibet 63 (Robert Barnett & Shirin Akiner eds. 1994).

Likewise in Tibet's far southeast—the town of Gyalthang in Kham province—the people initially drove back the communist army.

The early instances of resistance were exceptional. Most of Kham and Amdo initially accepted the arrival of the Chinese communist "People's Liberation Army" (PLA).

By 1950, PLA reinforcements had overwhelmed the rebels, so the survivors left home to pursue guerilla warfare from the mountains. Most of those in Amdo were wiped out by more reinforcements in 1953.

The PLA had first entered Tibet in 1949 and then much larger numbers came in March 1950. The communist soldiers claimed that they were just there temporarily to help the Tibetans and would leave thereafter. The troops were very polite, friendly, and helpful, and spent generously to boost local economies. They also worked on building roads. Not trusting communist promises, "Many people were buying British-made rifles from Datsedo [in Amdo] for their protection; in the Lithang area [far southeastern Kham] alone, about 1,500 were purchased." Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, Four Rivers, Six Ranges: Reminisces of the Resistance Movement in Tibet 11-12 (1973).

Invasion of Central Tibet

Having peacefully built a road network in Eastern Tibet, the Chinese communists used it to invade Central Tibet in October 1950. The Tibetan defending commander had previously torn down defensive positions. He fecklessly forced the Tibetan army and the Kham militia into a chaotic retreat. Soon he deserted, after giving orders that an ammunition depot be destroyed, thereby crippling the fighters he left behind. He later became a public traitor, and perhaps was treasonous from the beginning.

Three radio reports about the invasion were sent to Tibet's capital, Lhasa; but the central government did not respond, being busy with a five-day festival and picnic. The war was over in 11 days, with barely any resistance. The Chinese army was now across Yangtze River, inside Central Tibet, in a Kham ethnic area known as Chamdo. (Khampas live in both Eastern and Central Tibet.)

A better-prepared Tibet might have been able to turn back the 1950 invasion. The mountainous terrain and thin oxygen greatly favored the defenders. The Tibetans had very high motivation, especially compared to the PLA, many of whom were reluctant conscripts. Tibetans were much better fighters, and far superior with firearms and swords. By blocking the Chinese at the mountain passes from Eastern Tibet to Central Tibet, the Tibetan government might have repulsed the invasion.

Instead, the Lhasa government fielded a mere nine regiments led by a knave. Since 1933, a torpid and corrupt regency had been ruling Tibet, raking in the profits while the nation waited for the new Dalai Lama to come of age.

At the urging of the people and an oracle, the fourteenth Dalai Lama ended his regency in November 1950 and reluctantly took the reins of state. He was fifteen years old. While he had an excellent religious education, he had been taught little about worldly affairs. He was the head of state, but he did not control the kashag, the governing council. Nor did he control the big three monasteries of Lhasa, who dominated the government.

With Chamdo taken, the way to Lhasa was open for the PLA, but winter was coming. So the PLA concentrated on more roadbuilding. According to Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, who later led a unified resistance, if the Khampas and Amdowas had united in 1950 and been supported from outside, they could have prevented the completion of the PLA's road network into Central Tibet.

But as usual, the government in Lhasa failed to take measures for national defense, for fear of provoking the Chinese.

The Seventeen Point Agreement

The realities on the ground having changed, the Chinese coerced the Tibetan government into accepting a dictated "Seventeen Point Agreement," which the Tibetan National Assembly ratified in October 1951.

The agreement did nothing to protect Eastern Tibet (Kham and Amdo).

As for Central Tibet (U-Tsang), the agreement promised "no compulsion" in changing the social, religious, or economic systems. On paper, this was solid protection against the communists' "democratic reforms." What the communists meant by "democratic reforms" for Tibet was the same as for China: confiscating all the land, crops, and livestock, and forcing everyone into slave labor for the government. Whatever the laborers produced belonged to the government, which would return some to the producers. Often, so little was given back that people starved. Civil society and religion would be eliminated.

For Central Tibet, the Seventeen Point Agreement promised no "democratic reform" without democratic consent. In return, Central Tibet acknowledged Chinese sovereignty. Many in the Lhasa government favored rejection of the Seventeen Point Agreement, even though it would mean fighting sooner rather than later. As they knew, communist promises of fair dealing were expedient lies—like "honey spread on a sharp knife," as a Tibetan saying put it.

The main proponents of ratifying the agreement were the aristocrats and the most powerful monasteries, because of communist promises that they could keep their property and privileges. As they later found out, their reprieve would only be temporary.

To this day, the Chinese communists describe their invasion of Tibet as a "liberation" of serfs and peasants; to the contrary, the invasion was accomplished by communist collaboration with the most reactionary and selfish elements in Tibet. In both Eastern and Central Tibet, the Chinese quickly put many Tibetans on the Chinese payroll and enriched others with trade, forming a class of local collaborators and spies.

Under the Seventeen Point Agreement, the PLA established a large army garrison right outside Lhasa. Loudspeakers were set up all over, so that in Lhasa, as everywhere else in Mao's domains, there was a relentless blare of communist propaganda. Notwithstanding what the Seventeen Point Agreement promised, the Tibetan government was gradually rendered impotent, with only the Dalai Lama retaining some independence.

Initially, the Chinese did govern U-Tsang, and especially Lhasa, with a relatively light hand. The PLA recognized that its long-term occupation would require a strong logistical network. So while the communists rapidly built roads, they did not press their full program on Central Tibet.

Kham and Amdo, meanwhile, felt the entire weight of communism: the same famines, totalitarianism, forced labor, and destruction of civil society that characterized communist rule in China. For Tibetans, the oppression was aggravated by the Chinese communists' sense of racial superiority.

Resistance in 1954-55

Next to the Khampas and Amdowas, the largest tribe in Eastern Tibet was the nomadic and fearless Goloks, based in southeast Amdo. Their name means "backwards head," "rebel," or "bellicosity." Over the centuries, the Goloks had defeated Tibetan, Mongol, or Chinese governments that tried to tell them what to do. After the PLA burned some Golok monasteries in 1954, the Goloks declared guerilla war, which they waged from the mountains, with substantial support from the monasteries. "They waited until the PLA was drawn deep into their traps and then they slaughtered the godless enemy to a man." The PLA sent Amdowa emissaries to try to convince the Goloks to give up their guns, but the Goloks "would die before they would submit to disarmament." Mikel Dunham, Buddha's Warriors: The Story of the CIA-Backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet 142-43 (2004).

In the spring of 1955, the Chinese completed their roads deep into Central Tibet, all the way to Lhasa, the capital. With a foundation of physical control established, the communists were ready for the next step.

The communist occupation army in Kham ordered all weapons to be registered.

This was the last straw. No Khampa believed it would stop there. Overnight, guns were squirreled away. A Khampa's gun was the quintessential component of his worth as a protector of his family, home, and religion—no possession was more jealously guarded. If the Chinese wanted the Khampas' guns, they would have to fight for them. And that was exactly what many Khampas were in the mood for. No action so unified the Tibetans as the threat of disarmament. Tibetans who had seldom, if ever, joined forces with neighboring tribes, now met secretly to find ways to face the Chinese with a united front.

Dunham at 14. Many monks who had taken vows of nonviolence went through the ceremony to be released from those vows, so they could join the resistance.

The communist PLA showed up at Lithang Monastery, the biggest in Kham. The communists ordered that the monastery's large arsenal be surrendered. When the lamas refused, they were dragged to the courtyard before the townspeople, who had been forced to watch at PLA gunpoint. The Chinese yelled that they had been trying to civilize the Tibetans for five years, but the Tibetans still acted like animals.

So now the choice: White Road or Black Road. The former was peaceful surrender of arms. The latter road would be fighting the PLA and losing.

An elder lama stepped forward:

What is there to decide? Our own families will not give up what is theirs and has always been theirs. You Chinese did not give us our property. Our forefathers gave us our property. Why should we suddenly have to hand it over to you, as if it were yours in the first place?

Dunham at 150. For the time being, the Chinese backed off, preparing to send reinforcements in 1956.

The post Tibet's Armed Resistance to Chinese Invasion appeared first on Reason.com.