Midwinter. War in the Middle East. Energy crisis. Rising prices borne disproportionately by low-wage workers, particularly in a public sector squeezed by a “Tories in turmoil” UK government.

Not December 2023, in fact, but December 1973, as Britain prepared for the three-day working week that commenced on January 1. It arose after the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), with 250,000-plus members, interrupted the usual supply of coal to power stations with an overtime ban. The union was pushing for an improved pay offer from the miners’ employer, the state-owned National Coal Board (NCB).

Edward Heath’s Conservative government was determined to resist the miners’ claim. Factories, offices and shops deemed non-essential, because they were not providing food, medicines or other everyday vitals, received a government directive to operate either from Monday to Wednesday or Thursday to Saturday. Domestic power was rationed too. Household demand for candles, gas and paraffin heaters, and cooking implements soared. There was also petrol rationing and a road speed-limit of 50mph.

The situation was unprecedented in peacetime Britain. Andy Beckett, in his excellent 2009 book When the Lights Went Out, notes that economic output fell by 20%, while 1 million workers were made temporarily unemployed.

Despite the disruption, the miners enjoyed public support. This became evident when Heath called a general election, held on February 28 1974, seeking a fresh mandate for keeping public pay awards below the rate of inflation. A tight contest ensued, from which a Labour government emerged led by Harold Wilson. His first actions included resolving the coal dispute on terms closer to the NUM’s claim than the NCB’s final offer, and ending the three-day week.

What caused the crisis

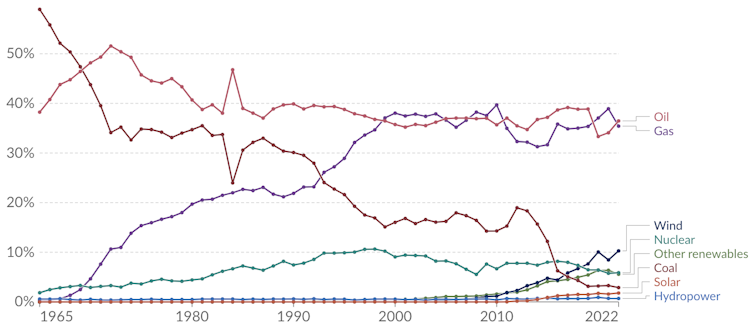

The crisis had been caused by the big switch in Britain’s energy market from coal to oil. Coal had been king as late as 1957, responsible for 80% of energy consumed in Britain. The situation began shifting, however, with an increase in imported oil from the Middle East.

Oil was cheap, and its energy share shot up to overtake coal in 1970. Accompanied by the rise of natural gas and introduction of nuclear energy, the coal miners felt this transition was unjust. Employment in the mines had halved in the 1960s. Job alternatives in engineering and manufacturing were not growing quickly enough to absorb further redundancies.

UK energy consumption, 1965-2022

A new generation of leaders including Michael McGahey, president of the Scottish NUM and vice-president at UK level, resolved to resist further contraction of coal while fighting for improved wages. This appealed to young miners, who were conscious of their vital social role in powering Britain’s homes and workplaces. Their sense of injustice was piqued by friends and relatives earning more in easier factory jobs, assembling cars and consumer goods.

They first mobilised for a national strike in 1972, the first since 1926. Remembered most for the mass blockade of Saltley fuel depot in Birmingham, this won the miners a big pay increase. By the autumn of 1973, however, with inflation running at 10%, most of this raise had been eroded.

The NUM’s overtime ban and the government’s radical reaction had an important additional trigger: the Yom Kippur war between Israel and various Arab states and combatants in October 1973. The oil producers’ cartel, Opec, which mainly comprised Middle Eastern countries, sought to pressurise Israel and its allies in western Europe and North America by instigating production controls. This accelerated a major price-surge in oil, from US$2 (£1.59) a barrel at the start of 1972 to US$11 (£8.74) two years later.

The 1950s and ’60s had seen the construction of dual-fuel power stations capable of running on coal and oil. Thanks to the surge in oil prices, they began running on coal only. This gave coal a sudden and unexpected advantage which the NUM exploited. Unsatisfied by wage negotiations and undeterred by the three-day week, the union stuck to its overtime ban. At the end of January 1974, members voted overwhelmingly for a continuous strike, starting on February 9. This was what prompted Heath to call the general election.

The present day

What is the significance of the three-day week today? Beckett argued that it made visible two important elements of the future of work. One was extended working time, with non-essential factories and offices running 12-hour shifts on their permitted days. This anticipated the intensified work that many employees experience today.

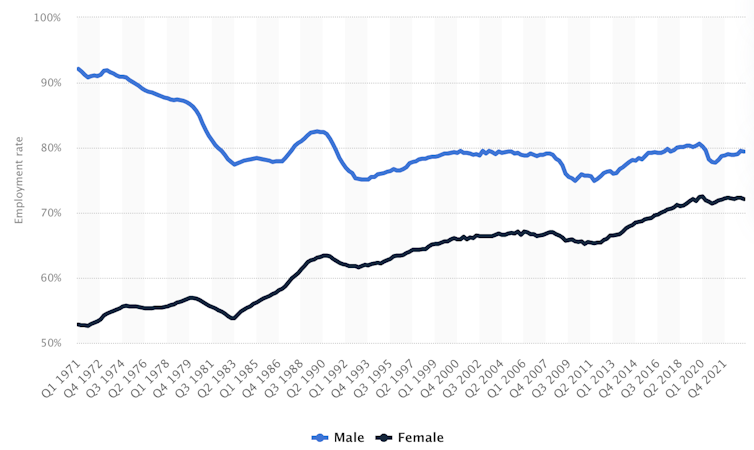

Changes in the gender profile of the workforce were also prefigured. At the time, women workers were disproportionately concentrated in essential services and retail. This meant they were employed normally during the three-day week, whereas there was enforced idleness among the greater clustering of men in non-essential industrial occupations. This trend increased as deindustrialisation gathered pace in the 1980s.

UK employment rate by gender, 1971-2021

Two further observations can be made, reflecting back on the three-day week being related to energy and the insecurity of essential workers. First, the energy supply remains insecure. The 1973 drama, while driven by the coal dispute, was aggravated by the external shock of Opec production controls and the five-fold oil price increase.

Our difficulties in 2023 are similarly multi-causal, but inflation and economic insecurity have been amplified, as in 1973, by oil and gas price hikes. This is partly because of embargoed imports arising from Russia’s war on Ukraine, but also the result of prices imposed on domestic and business users by private-sector energy providers in the UK.

Second, workers in healthcare, transport and other public services in the early 2020s have emulated the miners in disrupting everyday economic and social life through strikes. Just as in 1973-74, this action has carried public support because it targets the manifest injustice of low and falling levels of real pay among essential workers.

If the polls are accurate and Labour wins the next general election, likely to be held in 2024, popular unrest arising from wage and fuel insecurity will again have helped to defeat a Conservative government.

Jim Phillips has received funding from the Leverhulme Trust..

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.