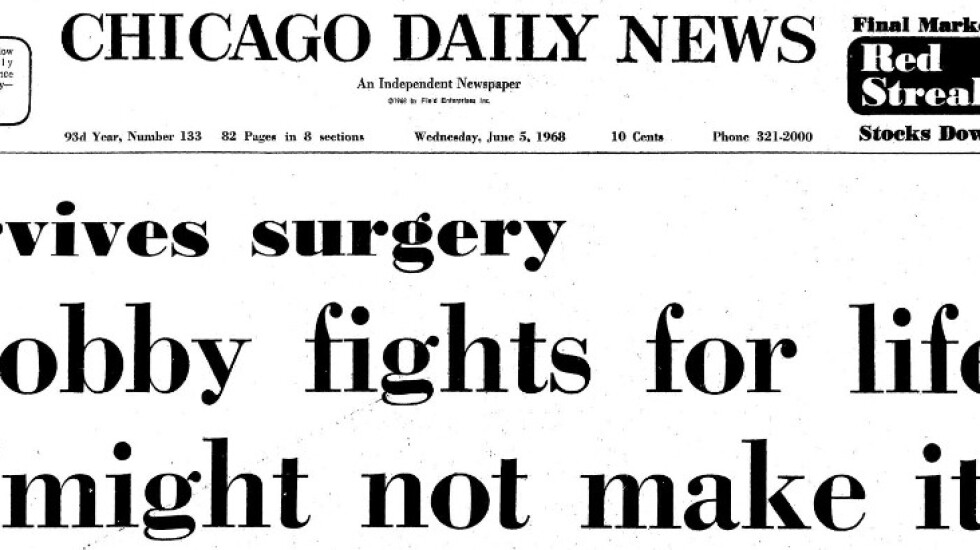

As published in the Chicago Daily News, sister publication of the Chicago Sun-Times:

Since its inception, the Chicago Daily News published every afternoon, Monday through Saturday. When it dropped on June 5, 1968, it’s likely that newspapers flew off shelves as Chicagoans clamored for any news on Robert F. Kennedy.

Just after midnight on that day, the senator and presidential candidate was shot while he was leaving through a hotel kitchen in Los Angeles. Kennedy had just won the state’s Democratic primary and seemed to have a clear shot at the nomination and the White House. The assassination happened at about 2 a.m. CT, so the Chicago Sun-Times had no coverage of the shooting that morning. It would’ve been up to the Daily News to provide some of the most updated coverage at that time.

After performing surgery on Kennedy, doctors gave him “a 1-in-10 chance for survival,” according to Daily News science editor Arthur J. Snider. He had resumed breathing on his own, and medical experts told Snider that if Kennedy survived, he would recover without any impairments, as the bullet had not hit the part of his brain tasked with “thought, cerebration, speech, sight and motor ability.”

“But the rest of the picture is grave,” the reporter wrote, “because the injury has involved the brain stem, the area that controls the heartbeat as well as the breathing rate.” And the bullet’s trajectory had greatly diminished the amount of blood flowing to the brain.

“The open question,” neurologist Dr. Eric Oldberg at the University of Illinois Medical School explained, “is whether there will be enough blood coming in to keep the vital centers going.”

Even if Kennedy did survive, politicos almost universally agreed he’d be dropping out of the race. And so between the shooting and the ending of a bright candidate’s career, Chicagoans woke up to a whole new reality.

The paper sent reporters Barry Felcher and John Gallagher out into city streets to collect local reactions to the shooting. At a tavern in Old Town in the early morning hours, 30-year-old Richard Cohn “catapulted out of his chair and ran toward the bar when he heard of the shooting.” He wondered aloud, “how much this poor family has to give.” In the same pub, housewife Wana Brandstetter cried, “What have we come to?”

As the Loop came to life and people rushed to work, Philip Samson, 42, told the reporters at State and Madison, “These gun laws aren’t worth a damn and this proves it.” He used to work at a firm on the West Side until the building was burned out in the riots after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination barely two months earlier. “They ought to stop worrying about places like Vietnam and start trying to figure out what’s wrong over here,” he added.

Outside the Wrigley Building, a Black ad executive who asked to remain anonymous said, “I cried this morning for the first time in a long while. America is in jeopardy; that’s all there is to it. It is not a question of race anymore. America is going to have to start to work together, and forget about ethnic groups.”

A chauffeur on Michigan Avenue wondered if this tragedy could have been prevented if national gun laws had been enacted in 1948 as troops returned home from the war. A secretarial student proclaimed the shooting “really is a disgrace to our country,” and a job-hunting man from Indiana called it “another sign of our social decline.”

The reporters then crossed paths with Rev. Thomas Sullivan, associate superintendent of Chicago Catholic schools, who told them, “The world seems to be coming apart at the seams.”

Then he added, almost prophetically given the events yet to happen in the city, “I wonder if this sort of thing might not lead to excessive law enforcement, though. They really may try to lay the law on heavy now, and that would be a mistake, too, I think.”

The next day, Bobby Kennedy died. He left behind a loving family and a country in for several rough years ahead.