As published in the Chicago Daily News, sister publication of the Chicago Sun-Times:

It’s safe to say that the Watergate scandal has touched nearly every aspect of American culture, so much so that it’s common to see the suffix “-gate” added to other words to denote a serious scandal — Gamergate, Nipplegate and Beachgate, to name a few.

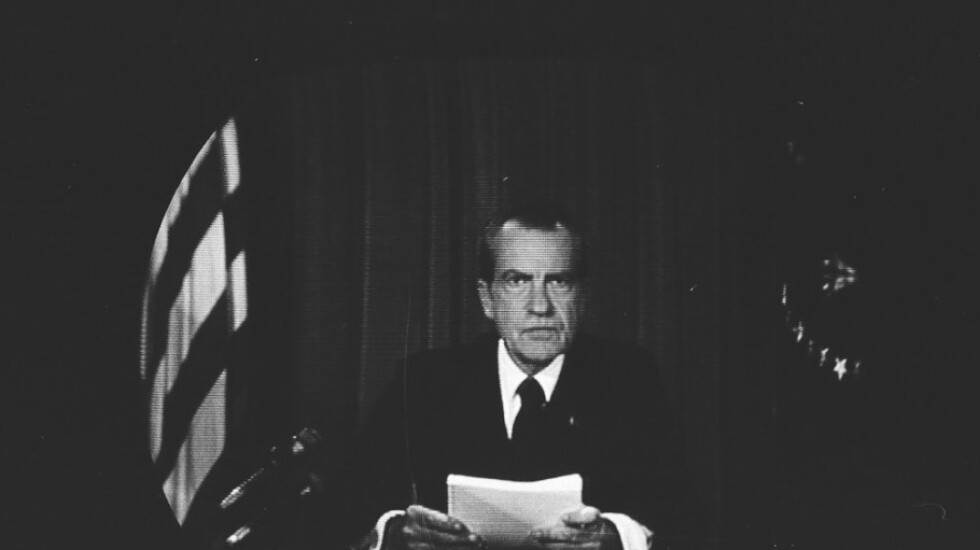

The original “-gate” scandal, in which President Richard Nixon and his associates attempted to cover up their involvement in the June 17, 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in a Washington, D.C., hotel, eventually resulted in Nixon’s resignation in 1974. The early reports that appeared in the Chicago Daily News show how the break-in investigation unfolded.

The first mention of the Watergate break-in appeared just two days after the incident.

“Democratic National Chairman Lawrence F. O’Brien wants a thorough government probe of an apparent attempt to bug his office that resulted in the arrest of a salaried employee or [sic] President Nixon’s re-election campaign committee,” a United Press International report read.

Already Nixon’s name was tied to the burglary attempt, and investigators already had a handle on the most basic facts. The break-in happened at about 2:30 a.m. on June 17, the UPI report said. Five men, including former CIA employee James W. McCord, had been arrested and charged with second-degree burglary.

The report said that McCord’s arrest was particularly noteworthy because he served as security coordinated for the Nixon re-election committee with a “take-home-salary” of $1,209 per month. Interestingly, Bob Dole, then serving as the Republication National Chairman, added that McCord also “holds a contract to provide security services for the GOP national committee.”

Metropolitan police investigating the crime told UPI that the men wore surgical gloves and carried extensive photographic equipment and electronic surveillance devices. “They said the instruments were capable of intercepting both telephone communications and regular conversations.” The FBI had opened its own investigation into the burglary.

The next day, O’Brien filed a $1 million damage suit against the Committee for the Re-Election of the President and the five “bungling burglars,” Washington bureau reporter William J. Eaton wrote. He painted the act as “very, very serious political espionage.” The reporter also noted that McCord lost his job.

It would take almost a full year for the court of public opinion to turn against Nixon. He was even re-elected in November 1972, winning 60% of the popular vote and every state except Massachusetts.

But even in the week following the Watergate burglary, Daily News columnist Joseph Kraft posited that if Nixon and his cronies were involved, then it shouldn’t surprise anyone.

“The central fact is that the President and his campaign manager have set a tone that positively encourages dirty work by low-level operators,” he wrote on June 26.

Kraft didn’t go so far as to declare Nixon guilty. In fact, he found it difficult to believe that there was anything in the headquarters worth running “the risk of being caught in the act of breaking and entering.”

The columnist did have one telling prediction:

“Unless the President and Mitchell clean up their own operations, they are going to pay a price,” he wrote. “They will find that they cannot get away with keeping the President above the battle.”