If we ever make contact with aliens, our best bet might be to say as little as possible.

A recent study, which uses game theory to simulate the outcomes of different strategies for communicating with aliens, suggests that the less we tell them, the better, at least at first. That’s because the less they know about us, the more likely they are to assume we think like them and have similar goals, and thus the more likely they are to cooperate instead of destroying us. University of Haifa psychologists Ilan Fischer and Shacked Avrashi published their work in the International Journal of Astrobiology.

“Humans benefit from extraterrestrials making choices while assuming humans are strategically similar to them,” Fischer tells Inverse.

Prisoner’s Dilemma…But In Space

To simulate how our first contact with aliens might play out, Fisher and Avrashi had a computer play about 100,000 rounds of a very simple game: Two players must each choose to either cooperate with or confront their opponent. If both players choose to confront each other, they lose points. If each player picks a different option, the confrontational player gets a small reward. And if both players cooperate, they both get a larger reward. (This game might sound familiar; one version of it is called the Prisoner’s Dilemma.)

"Both cooperation and confrontation are driven purely by a computational rationale," says Fischer. In other words, smart players don't choose to cooperate because they like being nice or confront because they’re annoyed, "but simply because it provides higher expected payoffs" says Fischer. So we don't have to assume aliens are friendly, just that they're strategically savvy.

The game is all about predicting what the other person will do and responding accordingly — and winning it requires you to be good not only at predicting what the other person will do, but at signaling your own intentions. And that, according to Fischer and Avrashi, is something humanity needs to keep in mind when we’re trying to make contact with intelligent aliens (if they exist). Players are more likely to cooperate if they think other players will make the same choice, so the best way to win at the cooperate-or-confront game is to convince your opponent that you think like they do and want the same things and will choose the same strategy to get them.

Playing Our Cards Close to the Vest

If you’re talking to another human, one you know something about, convincing them that you have common ground is (in theory) relatively easy. Just talk about having similar goals, values, experiences, or beliefs. But if you’re a SETI researcher trying to compose a message to an alien intelligence that you know nothing about, your best bet may be to say as little as possible, because any detail you share about humanity could let slip that we’re different from the aliens.

Imagine you’re playing a few rounds of Prisoner’s Dilemma with somebody you can’t see. How similar to yours would you expect their strategy to be if you learn that they are several decades older or younger, or from a different country? What if that “different country” is actually Enceladus, and they’re really a sentient octopus-like creature? How does a being like that even think? You have no way to predict what it might choose to do, and that means neither party can rely on the other to cooperate, so confrontation starts to look like the smart choice. If the stakes are potential alien invasion, the odds of everyone dying horribly just dramatically increased.

Fischer and Avrashi suggest three simple rules for communicating with a newly-discovered alien culture. First, don’t reveal anything about our goals or intentions. Second, don’t reveal anything about humanity, our biology, our technology, or our culture. And third, keep the message neutral and focus on similarity.

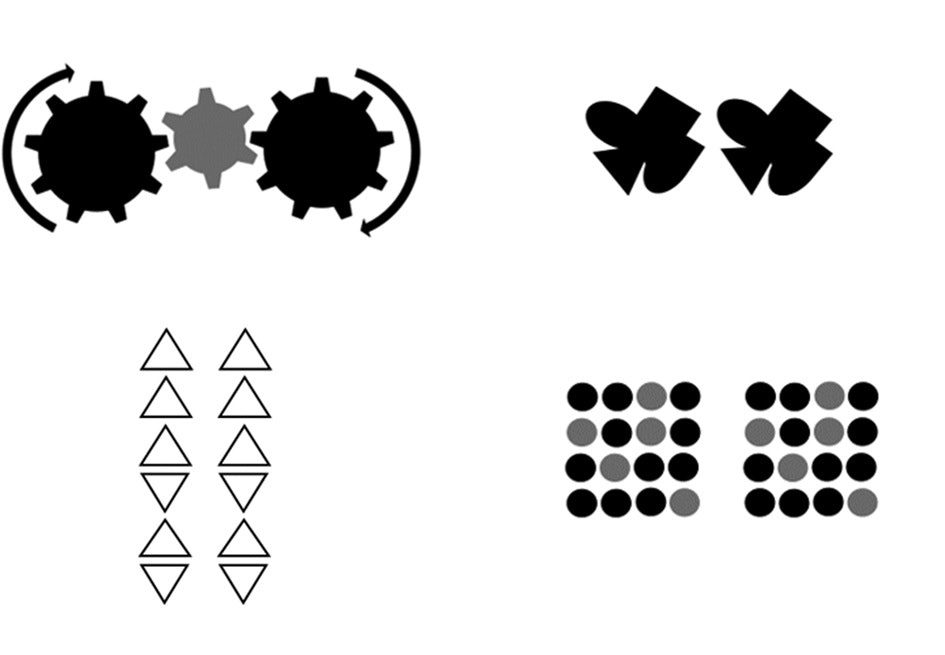

“The goal is not to convey information (since we can't predict how it might be interpreted), except for the concept of complete similarity,” says Fischer. “In fact, using multiple unrelated stimuli is suggested to prompt extraterrestrials to reject any specific interpretation tied to individual stimuli, leaving only the singular meaning of complete similarity.”

Fischer and Avrashi even provided some handily vague geometric symbols to help with that part.

The Next Steps Are More Complicated

Of course, eventually the conversation has to move beyond reassuring each other that we’re just so similar, we’re practically twins. And that’s where we have to step beyond the comfortably computational confines of game theory.

“It will make sense to slowly raise the stakes, that is, make relatively small trust building choices, taking relatively small risks, and slowly progress to more meaningful interactions with higher risks,” says Fischer. “It will likely require skills that extend well beyond game theory. Handling such communications will demand the best of humanity’s social, strategic, and cognitive abilities.”