One of the most iconic figures of the grunge era, Alice In Chains singer Layne Staley had stepped back from the limelight long before his drug-related death in 2002. Seven years later, in 2009, the band returned with new singer William Duvall, and as Metal Hammer found out, an album that turned tragedy into triumph.

“So, are we done here? OK yeah, thanks, have a good one…”

A smirking Sean Kinney’s just broken an awkward silence brought on by the ominous red light of a dictaphone. Jerry Cantrell shakes his head and laughs at the snickering drummer like a teacher does an unruly pupil, while bassist Mike Inez and new member William DuVall make a calming gesture at him with their hands. They’re all laughing – it’s a welcome ice-breaker on the cusp of what, clearly, is not an easy task. Alice In Chains’ history is nothing if not riddled with pain and twisted by speculation. Where to begin?

“Just pull it up on Wikipedia,” he continues with a grin. “If I want to know anything I just go on the internet and believe anything…”

That is not recommended. We’re saddled around a table in a dive bar tucked away amid the sun-baked grot of downtown LA. You have to marvel at the sheer unlikelihood of the occasion that brings us here. After all, the last time AIC sat down as a unit to talk about a new release was on the back of their self-titled third album in 1995. At some point in the geologic age that’s elapsed since then they not only dissolved but, in a move that would have seemed unfathomable just a few short years ago, regrouped with a new member, singer William DuVall, toured the world, and – this is the bit where you’ll want to ring Satan to double-check the weather in hell – written a new album. It wouldn’t have seemed so impossible were it not the for the tragic death of singer Layne Staley in 2002, whose loss casts an inky shadow over today’s proceedings despite a relaxed, even jovial atmosphere around the table.

To really understand just how unlikely today’s story is, you have to look back to what happened with Layne’s death, an event that seemed to seal the fate of the band whose crushingly heavy 1990 Facelift debut stormed the airwaves and spearheaded a so-called ‘Seattle sound’ that would soon rattle the globe. After all, when Layne passed away Alice In Chains hadn’t toured in six years. Not with a bang but a whimper, they’d played a mere handful of dates opening for Kiss in 1996 and, quietly, unofficially, disbanded, that year’s MTV Unplugged performance being not only their last, but a final testament to the group’s utterly colossal heaviness, even on an acoustic guitar.

You’d imagine that living off the trappings that come with having two number one records and – with only three studio albums – a staggering eight platinum certifications and six Grammy nominations would be easy. But with success comes excess and, as they’ll reveal today, ending the adventure that began when Layne Staley and Jerry Cantrell met in 1986 was about escaping the talons of substance abuse and their own demons. Sadly, the man responsible for bringing an abysmal depth to lyrics so heavy so as to seem encased in lead didn’t make it. In

The troubled died on April 5, 2002 at just 34 years of age. Horrifically, his body wouldn’t be discovered for another two weeks when police kicked in the door of his Seattle apartment to discover drug paraphernalia strewn about the place and an answering machine that no longer worked because its two-hour tape was full of messages that hadn’t been listened to.

You’ll only need to listen to Black Gives Way To Blue to comprehend just how loudly the immensity of that loss still echoes today. As Alice In Chains will explain, the mournful cadence of their fourth studio album begins in the aftermath of that cold day in April 2002 when Layne’s banshee-like wail was finally silenced, but – as they’ll explain in different ways – Black Gives Way To Blue isn’t simply about their friend’s death. It’s about what you do when your pain reaches a threshold and you agonisingly decide that it’s time to move on.

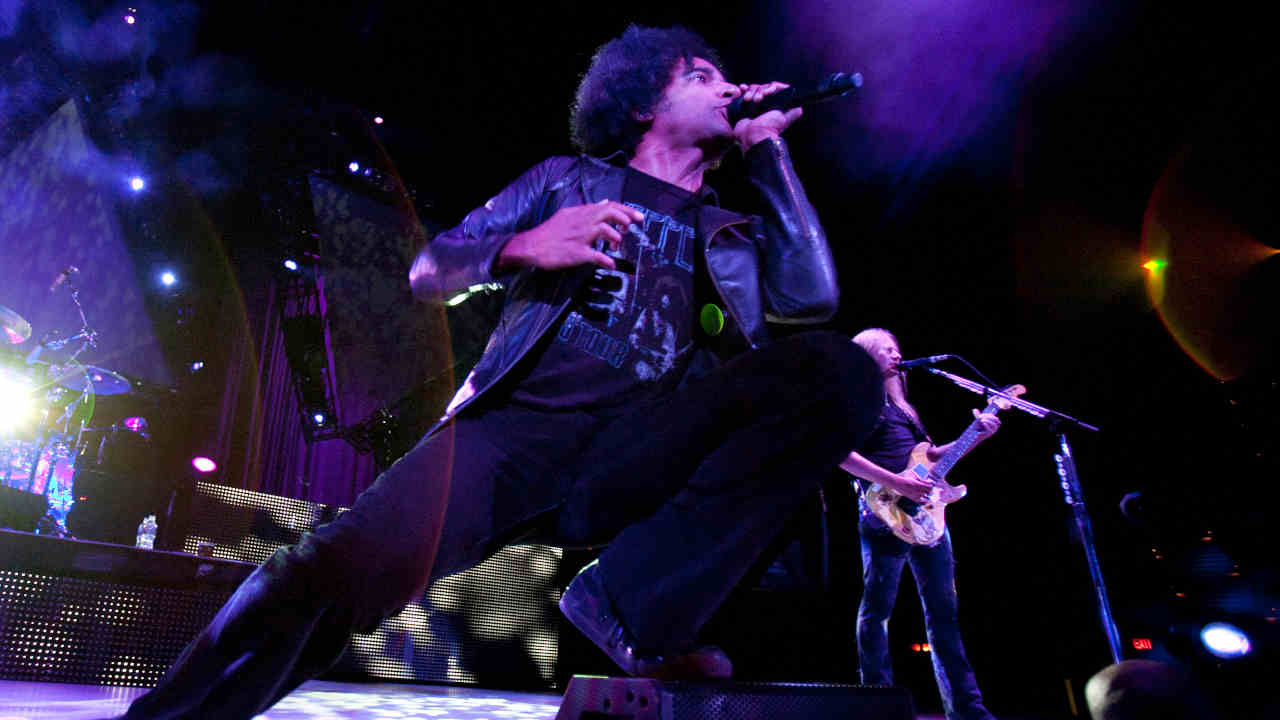

The next chapter began in 2005 when a stir-crazy Sean Kinney organised his surviving bandmates to play a tsunami benefit concert with Damageplan vocalist Pat Lachman and other guests like Tool’s Maynard James Keenan, Puddle Of Mudd’s Wes Scantlin, and Heart’s Ann Wilson. A world tour followed with William on the mic, but while the rapturous response to those 86 sold-out shows was undeniable, the band seemed reticent to answer questions about whether this was anything more than a trip down memory lane. They went quiet, but as Jerry says, there was much afoot, though there was no immediate decision to reform and write. He’s gruff but candid, punctuating his speech with a deep- throated cackle that betrays years of smoking and experiences that can make even laughter sound forlorn.

“We started writing in November 2007,” he says. “We went on a couple of tours first before that, but was more a celebration of the music, and we felt right about doing it. It’s like we were thanking our fans, but if you get together for any length of time, and there’s a drum set, somebody’s always rocking on something, if it’s good, you record it, and after two years you get a lot of good shit. By March we were talking about starting to mould this shit.”

The band would soon do so at Studio 606 in LA, owned by longtime band-friend Dave Grohl. A hesitating affair, even the act of recording didn’t mean the decision had been made to release an album. First, they had to ascertain where their hearts were at.

“There was no master plan, despite what people think,” he continues. “This felt right, so we did the next thing, and then the next thing… It’s more than just making music and it always has been. We’ve been friends a long time. We’re not doing this to please anybody. It had to be OK from here,” he says, pointing to his chest.

As it happens, it was, but when news first surfaced in 2008 that the group had entered the studio, it was met with a coarse reaction by some fans who seemed to see the move as a betrayal of Layne’s memory.

“To continue that legacy, for us it’s a big move to fucking stand up and move on,” says Sean, sounding indignant at the reminder. “The music connected so strongly with some people. It’s amazing that they have such a connection but they seem to act like it happened to them. But this happened to us and Layne’s family, not them. This is actually our lives, so we appreciate that but it’s irrelevant. If we can be OK with it why can’t you? This happened to us, this didn’t happen to you. You listened to our records and now you’re bummed out? Imagine how it is for us! If we’re proving that we can move on and fucking continue to live and set some example, then people should too. The point of this record is so personal to us, but it’s a bigger universal point. We’re all going to fucking die, we’re all going to lose somebody, and it fucking hurts. How do you move on? We stopped playing when we lost hope, we quit talking to people like you when we lost hope. If we’d rode it out we’d all be dead now. It was always a survival thing. This record is us moving on, and hurting. That to me is a victory. I already feel like I won…”

“It’s harder for us,” says Mike, finally. “Layne is irreplaceable, he’s gone, and that takes a lot of adjustment. We did a whole world tour just to be sitting here talking to you about a record. This is hard for us. We had to bury our brother.”

The statement hangs in the air. The band nod in agreement and for the first time their sense of grief is palpable. They may have healed, but scars remain.

“Lost a brother, gained a brother!” blurts William. Laughter all around.

Of course, there’s more to this than the tour. The positive response to their live shows with William fuelled the decision, but then William – a veteran frontman of Atlanta-based heavy rockers Comes With The Fall – was no stranger to the band and its creative core Jerry Cantrell; their almost fraternal bond is deep-rooted. Softspoken, thoughtful, and almost infuriatingly polite, he quickly dispels the myth that he’s a hired gun. He’s known Alice In Chains for years, including Layne.

“I moved here with Comes With The Fall in 2000 and Jerry was really into us,” he explains. “From there we sparked a friend- ship and a mutual admiration and then in 2001 he was finishing up his Degradation Trip album and he needed a band to help him out on the road, so for all of 2001 my band opened the show and did double duty backing him on his own material, and that was solid touring. When I say 2001 and 2002, I mean all of it, and you get to know somebody. It’s not like this thing was glued together, we met on a street three years ago. There’s a long story to get to this point. I’ve known these guys almost 10 years. As step by step as this has gone, as manic as it has been over the last three years, seven years prior to that lives converged and now here we are. We were friends when Layne was living, he passed while we were on the road.”

Still, the thought of taking the place of one of the 90s’ greatest icons – someone whose voice isn’t just synonymous with Alice In Chains’ unparalleled ability to summon despair and melancholy and expel it through an amp is a major proposition. Big shoes to fill? On that, William is circumspect.

“No one wants to sully any legacy or disrespect Layne,” he says. “I love Layne, I love his work. The only way to honour the past and the present is to do your thing but also do it in a way that hopefully is a bit more life-affirming instead of revisiting the death-trip. It’s about redemption and rebirth. It’s about owning it in my own way, or it would be a disservice to me, the people who care about this band, and to Layne.”

“And the truth is we’re making it up as we go on…” adds Jerry, picking up where William trails off. As it happens, Black Gives Way To Blue was finished before Alice In Chains had worked out the particulars of how it was going to be distributed, and they bankrolled the endeavour themselves, seemingly to hedge their bets in case it didn’t work out – a self-imposed get-out clause. It wasn’t cheap.

“It’s a hell of a risk because it’s all on your ass,” Jerry continues. “But that’s kind of a lesson that comes up again and again. We’ve put our asses on the line before and it has paid off. When it started we just wanted to put a gig together, we were like, ‘Fuck yeah let’s do it.’ That turned into jamming stuff and the next thing you know we’re on the road somehow. It’s been a natural thing. You start making progress and you get positive reinforcement that you’re doing something good. You take on some challenges – we’ve played some great fucking shows, to amazing crowds, and that helps. Guys that you admire, seeing them, the community of our friends is so fucking supportive. And there’s a whole generation of people that won’t see us because they weren’t born.”

Still, that’s a potentially calamitous step back into the fray. Given that the band’s various experiences with substance abuse – remember that 1992’s Dirt album is overridingly an album about their experiences – to return to the environment that lead to their ruination and ultimately Layne’s death is no small risk.

“Well hopefully we’re a little fucking smarter!” chuckles Jerry. “It wasn’t just Layne, we were all fucked up. Young kids, lots of success, you throw down and have fun and then you make some money and you do well – you’re kind of expected to be a fuck-up. All that shit your folks told you? Turns out it’s true. We weren’t like, ‘Yeah, woooo, heroin!’” he says. “Yeah, it was dark, man, that was our life. With Layne, it’s so easy to go ‘Junkie, dead!’” he says, pounding the table and startling all present. “He was a hell of a lot more than that and we were lucky enough to know the rest of him too.”

If Alice In Chains’ tour was a means of coming to terms with life after death, then Black Gives Way To Blue is the last stage of catharsis, a triumphant exit from the darkness; a monumentally heavy, dirge-laden slab of riffs and the signature wail of distortion and poignancy that’s given the best of their music its crushing gravitas and timelessness. Check My Brain is made to dominate airwaves, A Looking In View a collapsing wall of growling leads and choruses that seem to float in and out like an ebbing tide. It isn’t merely that, sonically at least, it has total continuity with their back catalogue. Their trademark, stark confessionals – autobiographical but universal enough to connect with anyone who’s endured pain, are there too. It’s more than a band resurrecting itself. It’s the sound of victory. And, for Sean and Jerry, it was an opportunity to heal.

“From the first moment we started doing this stuff and it started becoming real to me, how important it was to really move on – I was still fucked up,” Sean admits. “I was still partying, and drinking and did a lot of drugs and it got to a point where I was just about dead in a hotel room – music’s the one thing that saved my life all along. I can’t do this and be genuine about it and be fucked up. After all that’s happened I was like, ‘I’m dying in my room – I can’t tell people it’s OK to move on with your life when the end result is that you’re also fucked up.’ I had to make a choice and do something as pure and as genuine as fucking possible.”

Listen closely to the final, title track of the album and you’ll hear a masterwork of acoustic balladry, a sad hymn written by Jerry from Layne’s perspective. Jerry reveals that once it had been written he knew an album was on its way, that Alice In Chains could ride again. And, more importantly, it allowed him to come to terms with the emotions that come with confronting loss and liberating oneself to live again. ‘I don’t want to feel no more, it’s easier to keep falling’ read the lyrics.

“Well, that,” says Jerry, taking in a deep breath. “Yeah. It’s a heavy tune man, I’m really addressing it in that frank a way – it’s cool now but it wasn’t cool then. When we recorded it it was hard to fucking sing that shit and hold it together. I think there was a real chunk of undigested grief and luckily everybody reacted to it that way too and really deal with it in a beautiful way for our fucking friend. I couldn’t leave my house for three weeks, I had mystery migraines, I was in so much pain, I was getting cat scans, I thought I had meningitis. I thought I was going to fucking die, I thought I had a brain tumour. It took a couple of months to get better. It was all still locked inside. I played it to Sean and he was like, ‘We never pulled any punches so don’t do it now.’”

“Jerry did that and we had the discussion where we were like, ‘If we’re gonna do this let’s fucking do this’,” continues Sean. “From the first thing said on that record to the last it’s pretty heavy. There’s no other reason to do this shit, Will came in and manned up, we bit the bullet and did the shit we needed to. The chemistry just worked. It wasn’t us trying to fuck it up. We were doing everything we could to enjoy life and fuck things up for ourselves but this was a tremendous undertaking. It’s another one of the best parts of my life. It’s going to be interesting to see where it goes because our last trip was one hell of a ride. I hope this one has a happier ending.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer 199