A colossal ancient species of whale that lived 39 million years ago was a true heavyweight, weighing more than double a blue whale and likely earning itself the title as the heaviest known animal to have ever lived.

The newly described basilosaurid (a family of extinct cetaceans), called Perucetus colossus, eclipsed blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) in sheer weight with an estimated body mass of between 187,000 to 750,000 pounds (85,000 to 340,000 kilograms). It had an estimated body length of about 66 feet (20 meters) — longer than a lane at a bowling alley, according to a new study published Wednesday (Aug. 2) in the journal Nature.

Paleontologists discovered the partial skeletal remains of the monstrous marine mammal 30 years ago in what is now Ica Province in southern Peru. Since then, they've unearthed 13 vertebrae, four ribs and a hip bone, according to a statement.

"[One of my co-authors] was looking for fossils in the desert in Peru and saw an outcropping of bones," lead author Eli Amson, a paleontologist and curator of fossil mammals at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History in Germany, told Live Science. "Digging out the fossils took a lot of time because of their sheer size. Each vertebra alone weighs 150 kilos [330 pounds]."

Related: 'Truly gigantic' Jurassic sea monster remains discovered by chance in museum

Researchers can only estimate how enormous P. colossus was using the limited number of bones they unearthed, as much of the animal's remains have decayed over time — including all of its soft tissues.

However, the bones they did recover were very dense, meaning they weighed a lot. To compensate for this heavy skeleton, the team believes the whale's soft tissues were likely lighter in weight than the bones, offsetting its heavy skeleton and helping it become more buoyant, according to the study.

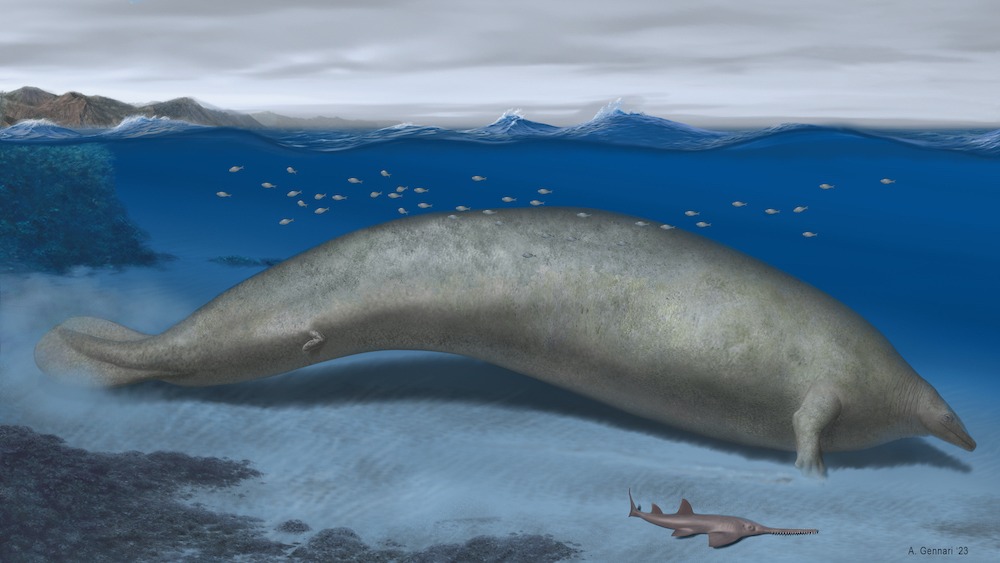

As a result, P. colossus likely had a very weird appearance. The team likened it to a modern manatee, but with a tiny head, an enormous body and little arms and legs. "It might have looked much weirder than we think," Amson said.

"In terms of weight, P. colossus was definitely bulkier than a blue whale. But the overall body length was shorter than the blue whale [and measured] 20 meters (66 feet). It's hard to estimate exactly how much blubber and soft tissues surrounded its skeleton, and so we went with a rather conservative approach with our size estimates," Amson said.

But that weird appearance may have helped it to remain buoyant and enabled it to glide slowly through the water, similar to manatees (genus Trichechus), the researchers wrote in the study.

Not only does P. colossus shatter our perceptions of what the world's heaviest animal might have looked like, it also challenges what we know about the evolution of cetaceans. This discovery means they reached their peak body mass 30 million years earlier than originally thought.

"P. colossus completely changes our understanding of evolution and extreme gigantism in cetaceans," Amson said. "It was most likely a slow traveler and a shallow diver. We're not sure what it ate since its head and teeth didn't survive. It's only speculative, but we think it spent most of its time at the bottom of the ocean not burning a lot of energy to get its sources of food."

Jeremy Goldbogen, an associate professor of oceans with the Hopkins Marine Station at Stanford University in California, who was not affiliated with the paper, said that studying P. colossus can offer new insights into the evolution of marine giants.

"The described species, Perucetus colossus, was clearly a large animal, and it had a heavy skeleton," he told Live Science in an email. "Was it bigger than a blue whale? Maybe it was and maybe it wasn't. I would argue that [the] more important questions relate to the evolution of entire groups of related species and the biology underlying when and why they got big."

The specimen is currently being housed at the Natural History Museum in Lima.