Does the discovery of a Ming Dynasty Buddha sculpture found near Shark Bay in remote Western Australia “rewrite history” and suggest the Chinese first visited Australia 600 years ago?

Probably not. The fleets of Ming admiral Zheng He are said to have had the engineering strength to navigate treacherous seas, but no solid archaeological evidence can confirm they ever visited Australia.

But even without this evidence, there is a long history of Chinese people in WA that may explain the presence of the Buddha.

Ian MacLeod of the Western Australian Museum identified that the Buddha was buried between 100 and 150 years ago.

Indeed, there was a large Chinese community living in Shark Bay in the late 1800s.

Asians in Australia

Asian boats visited Australia’s north and northwest coasts long before the first European settlements popped up in WA in the late 1820s.

From as early as the 1500s to 1906, hundreds of fisherpeople from Makassar on Sulawesi and other islands in today’s Indonesia made annual voyages to northern Australia, especially the Kimberley region and Arnhem Land. Some Makassans married Aboriginal Australians.

These fisherpeople were professional collectors and traders of trepangs, or sea cucumbers, highly prized in China.

Makassans bridged trade between Australia and China, and they may have brought Chinese traders – in Makassar at least since 1656 – to Australia in the 17th century or earlier.

However, no current archaeological evidence can support this.

Chinese Western Australians before 1901

The first documented Chinese Western Australian, Moon Chow (周满), arrived in 1830. A skilful carpenter in the newly established Swan River Colony, Moon Chow married, had kids and lived in Fremantle until he passed away in 1877.

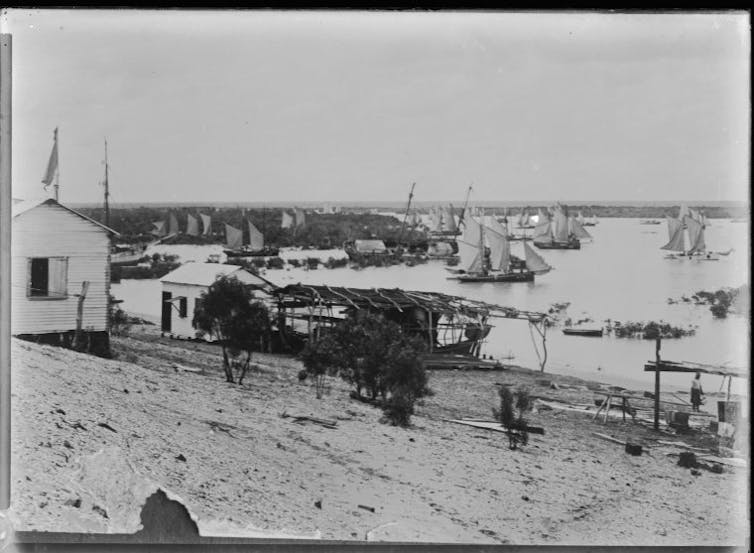

In the early 1870s, a bustling pearling camp emerged at Notch Point on Dirk Hartog Island, Shark Bay, featuring a Chinese settlement called the “Canton”.

Historian Anne Atkinson gathered the stories of some of these migrants in her book Asian Immigrants to Western Australia. We have recently digitised the Atkinson Collection and have analysed the information on people of Chinese heritage present in Shark Bay before 1900.

Most of these individuals were involved in the pearling industry, owning boats and gear or working for local pearlers. One local, Ah Wee, owned two pearling boats, pearling gear, two dinghies, two iron houses and livestock worth a total of £117 in 1886.

His family, and a number of others, were more than affluent enough to have owned the Buddha sculpture.

Other members of the community were employed in diverse roles such as cooks, sandalwood workers, station hands and general servants. Many are recorded as owning houses made from canvas or hessian. A few who were more affluent owned corrugated iron houses.

Life in Shark Bay was challenging for many Chinese Western Australians in the 1800s. The Atkinson records reveal the prevalence of violence, including murders, suicides and suspicious deaths.

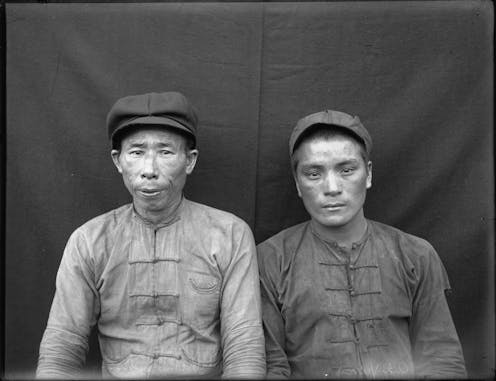

Chou Jum (Jim) Chu, Lo Yu Kwong and U.A. Tong were sandalwood workers employed by Leopold von Bibra at Wooramel, Shark Bay in the early 1880s. Jim Chu died in 1884 while working. His two Chinese friends testified he had been murdered by von Bibra.

The court case provides glimpses into the complexities of Chinese life in Shark Bay: unequal pay, difficult work conditions, systemic racism and regular disputes with employers over working conditions.

As with so many similar cases where abuse of Chinese labourers was alleged, von Bibra was found not guilty.

The Canton continued to be home to a large number of Chinese pearlers until the local European pearlers in Shark Bay established the “European Association” in 1886 and pressured the government to exclude Chinese and Malays from the local pearling industry.

Their lobbying paid off, leading to a violent and brutal closure of the Canton, home to 102 Chinese and 68 Malays at the time. Some left Australia; many moved down to Perth and became market gardeners; others went to work on cattle stations as labourers or cooks.

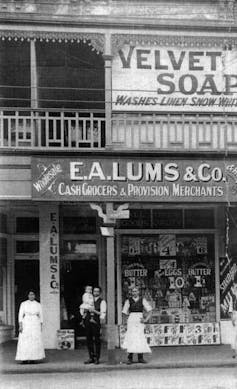

Hae Sam was a fisherman in Shark Bay from 1873 to 1876. He then became a market gardener in Cannington and then Maylands in the 1880s, before owning a fruit and vegetable shop in Fremantle in 1890.

His descendants still live in WA.

Continuing connections

The White Australia policy, enshrined in law shortly after the Commonwealth of Australia’s inauguration in 1901, overshadowed the diverse interactions between Australia and Asia in previous centuries.

At the time of federation, 1,459 male and 16 female WA residents were identified as born in China.

During the initial period of the White Australia policy, due to a desire to alleviate labour shortages, WA offered a relatively welcoming atmosphere for Chinese workers, compared with the eastern states.

As a result, the first commonwealth census in 1911 revealed a small but growing China-born population in the state, with 1,601 males and 20 females.

As the White Australia policy persisted, the China-born population in WA experienced a sharp decline from the 1920s onwards, dropping to just 227 males and 86 females in 1961, when the population reached its lowest point.

Although the White Australia policy ended in 1966, it was not until the 1991 census that the number of China-born WA residents surpassed the figure reported in the 1911 census.

In the 2021 census there were 28,415 China-born WA residents, among whom 36.7% were Australian citizens.

Regardless of when and how the Buddha sculpture arrived in Shark Bay, it reminds us of the long and changing history of Australia-Asia connections.

Benjamin Smith received funding for the Digitisation Centre of Western Australia as Lead CI on the ARC LIEF Grant LE200100123.

Yu Tao does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.