Medical technology has come a long way over the last few hundred years — doctors no longer perform milk transfusions or inspect a patient’s humors. But “when it comes to labor and birth, it hasn’t really progressed over the last couple of centuries,” Shireen Jaufuraully, an OBGYN and researcher at University College London, tells Inverse.

In fact, if doctors from two hundred years ago time-traveled to the present day, they would likely recognize the metal forceps and speculums that obstetricians currently use.

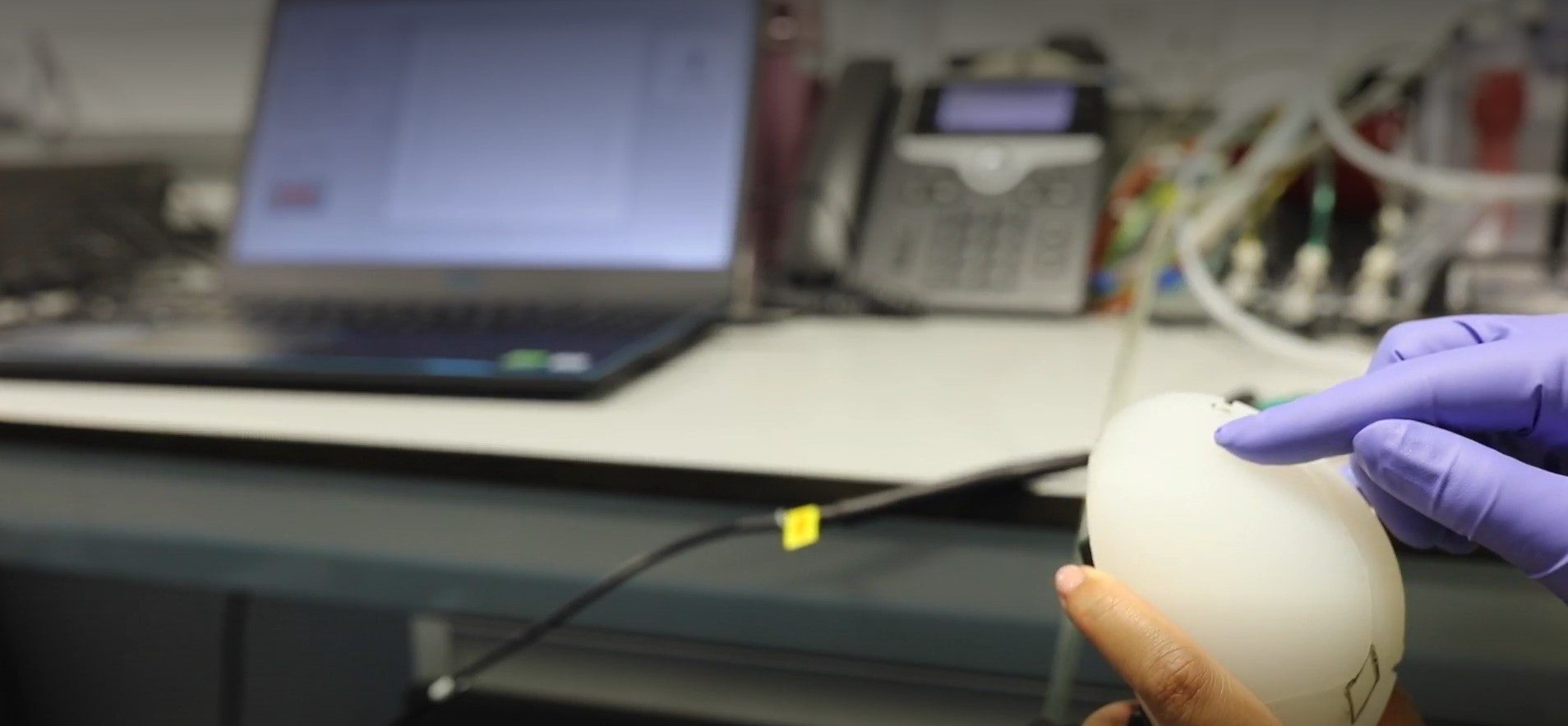

That’s why Jaufuraully and her team want to give obstetrics a 21st-century makeover. They recently published plans for a new sensor printed on a surgical glove that doctors can use to detect a baby’s birth positioning during labor, according to a new paper in the journal Frontiers in Global Women's Health.

This technology could help prevent birth complications associated with dangerous fetal positioning. And at less than $1 a pop, the glove sensor could offer an affordable solution for hospitals located in underserved areas.

Here’s the background — During birth, babies usually exit the birth canal in a specific position — ideally, head down, chin tucked, and back facing up (this is called anterior or cephalic presentation).

Doctors and midwives can deliver babies in other birth positions, such as face up or feet first, but these poses could injure the newborn or parent. So doctors must anticipate which way the baby is facing before delivery.

Why it matters — Healthcare providers typically feel the pregnant person’s abdomen during routine third-trimester checkups. Ultrasounds offer a slightly more high-tech and accurate option, but these tests can be expensive and might not be available for everyone. The UCL scientists hope the new glove sensor can help healthcare providers determine a baby’s position during labor more accurately, easily, and inexpensively.

What’s new — The flexible sensors can be printed onto any type of surface, including standard-issue sterile surgical gloves. They work by harnessing a phenomenon known as the triboelectric effect. “Basically, when they come into contact with a material or are rubbed against the material, they produce a current,” Carmen Salvadores Fernandez, a mechanical engineer at the University College London and co-author of the study, tells Inverse. This is, incidentally, the same process that creates static cling in your laundry.

The strength of this current fluctuates depending on the amount of pressure applied to the sensor, as well as the texture of the surface it comes into contact with. This phenomenon allows medical providers wearing the glove to determine how much force they’re applying to the baby. By inspecting sutures — a peculiar feature of the baby’s skull — they can figure out which way the newborn’s head is facing.

“You can imagine a baby’s head like the Earth’s tectonic plates,” Jaufuraully says. The “plates” in this metaphor: unfused pieces of skull bone, which meet at “seams” called sutures. These sutures can indicate which piece of skull obstetricians are touching, helping them determine whether a baby is facing down, up, or in a tilted configuration.

They can also figure out whether they’re applying the right amount of force, which can be hard to gauge. “We’re basically trying to quantify these things a bit more,” Salvadores Fernandez says.

To pair with the glove, the team developed an app with a simple, user-friendly interface that lets doctors know whether they’re using the correct amount of force — it lights up green for “yes,” red for “no.”

What’s next — The scientists still face a few data-processing hurdles, according to Salvadores Fernandez. For example, the sensor’s triboelectric signal is sensitive to outside “noise” from all the other tissues and fluids in the birth canal. Moving forward, the team will need to fine-tune their app to separate the signal from the noise.

It currently has a major advantage: Sensor production is inexpensive — it costs less than $1 per glove. And, Jaufuraully says, “it has the potential to be so much cheaper” once the manufacturing process is scaled up and streamlined.

So far, Jaufuraully and Salvadores Fernandez have only tested their glove sensor using realistic silicon models of babies and birth canals. But they hope to get approval for human trials and eventually get their gloves into hospitals — especially in rural areas and developing countries, where expensive ultrasound machines might be hard to come by.

In the long run, this simple solution has the potential to save lives, which was the researchers’ ultimate goal. “I do see exciting things in the future,” Salvadores Fernandez says.