If you’re a driver, particularly in the country, you could be forgiven for thinking potholes have become a design feature of Australia’s local roads.

You would certainly know they are in a state of disrepair. And you have every reason to be fed up, because bad roads are dangerous, they increase your travel time, and they force you to spend more on fuel and on car maintenance.

They are getting worse because we’re not spending enough to maintain them.

Three-quarters of our roads are managed by local councils.

Every year, those councils spend A$1 billion less on maintenance than is needed to keep those roads in their current condition – let alone improve them.

The underspend is largest in regional and remote areas.

New Grattan Institute research finds the typical regional area has a funding shortfall of more 40%. In remote areas, it’s more than 75%.

Federal funding is falling behind

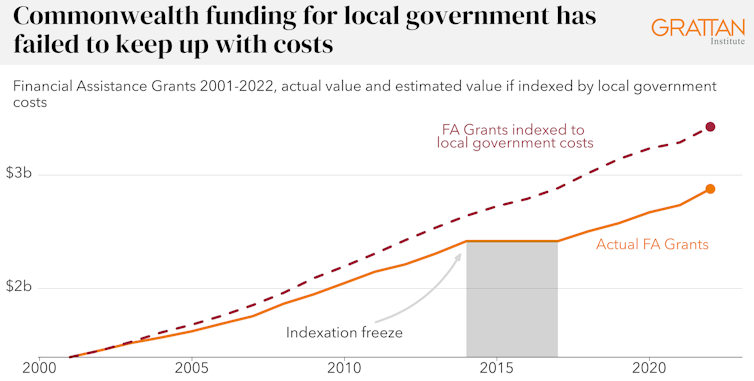

One reason for this underspend is that untied federal government grants to local councils haven’t kept pace with soaring costs.

Councils raise most of their own revenue – 80% on average. But in large parts of the country, there are a lot of roads and not enough ratepayers to pay for them.

Rural and remote councils have limited ability to raise more revenue from ratepayers. Their ratepayers already pay higher rates than those in cities, despite having lower average incomes.

Rate caps in place in New South Wales and Victoria also make it difficult for councils to raise more revenue.

Councils receive top-up grants from the federal and state governments. The primary grants from the federal government, available for councils to spend as they see fit – including on roads – are called Financial Assistance Grants.

These are worth about $3 billion a year.

But their value has not kept pace with rising costs. If they had kept pace, on our estimates they would be 20% higher, at $3.6 billion per year.

Road use is growing, but maintenance isn’t

Another reason for the underspend is that even as funding dries up, we’re using roads more.

A growing population means both more cars on our roads and more trucks needed to keep our shelves stocked.

But despite the extra damage to our roads, spending on maintenance has stalled.

Councils are spending more on other things

Another reason roads are underfunded is that councils are coming under increasing pressure to fund other services.

The legislation governing councils doesn’t clearly define what councils are responsible for, and there is no shortage of services communities want.

Spending on transport has fallen from almost half of local government spending in the 1960s to 21% today.

Environmental protection was only identified as its own area of spending for councils in 2018, but it now makes up 15% of all council spending.

Delaying will cost us more

If we don’t act now and start spending more to fix our roads, the pothole plague is going to spread. Australia is getting hotter, with more rain and floods.

The Local Government Association expects the cost of repairing flood and rain-damaged roads in the eastern states and South Australia to top $3.8 billion.

Tight budgets make it tempting to delay maintenance.

But delaying will only end up costing more in the long run, leaving taxpayers paying more to fix more badly damaged roads.

Finally, a circuit-breaker

Some might argue that now is not the time for more spending on roads, given pressures on the budget. But plenty is being spent on big roads and new roads.

Infrastructure Minister Catherine King’s recent announcement of a funding boost of for local roads is a very welcome circuit-breaker.

She announced the Roads to Recovery program will increase gradually from $500 million to $1 billion per year, the Black Spot program from $110 million to $150 million per year, and funding for an amalgamated Bridges Renewal and Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity program will climb form $150 million to $200 per year.

This decision is important. Not only will councils receive more funding for maintenance, but it will be predictable funding, enabling better stewardship of long-lived assets. The money can’t start flowing soon enough.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute’s board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and Grattan uses the income to pursue its activities. Marion Terrill does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any other company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Natasha Bradshaw does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.