Immediately after executing a cracking shot through the covers, earlier this week Australian batsman Steve Smith famously declared "I'm back, baby". After being hopelessly out of form for several years, middling the ball on one of his favourite shots, Smith immediately knew he was back in the groove. Commentators were quick to note, "It's an ominous sign for opposition teams this summer."

Closer to home, if bogong moths could talk, this week, they'd also be proudly announcing "I'm back, baby". Not just back from a run of outs, but back from the brink of extinction.

Once so common as to be a nuisance to many on their annual migration from their breeding grounds in western NSW and Queensland to aestivate (a state of dormancy similar to hibernation but which takes place in summer rather than winter) in granite caves in the high country, in recent years the much-maligned moth has been alarmingly missing in action.

In fact, in 2019, after decades of gradual decline in the population, scientists reported a catastrophic drop in numbers. Mountain caves that in previous years were packed with as many as 17,000 moths per square metre contained merely a handful, or worse still, none.

As a critical part of the high country ecosystem (the critically endangered mountain pygmy-possums rely on them as a food source), this decline has been of significant concern. Indeed, just last year they were added to the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

It is generally agreed among the handful of scientists studying the moth that changing farm practices drove some of the decline in moth numbers observed between 1980 and 2016, and that the sudden crash in numbers from 2017 was most likely due to severe drought and extreme heat in its breeding grounds.

Given this bleak outlook, imagine my excitement when earlier this week an email lobbed into my inbox from Myffy Rae in Kingston saying she'd spotted a lone bogong moth on her third-floor balcony. Having not seen one at the Yowie bunker for several years, my heart raced. Could they be back?

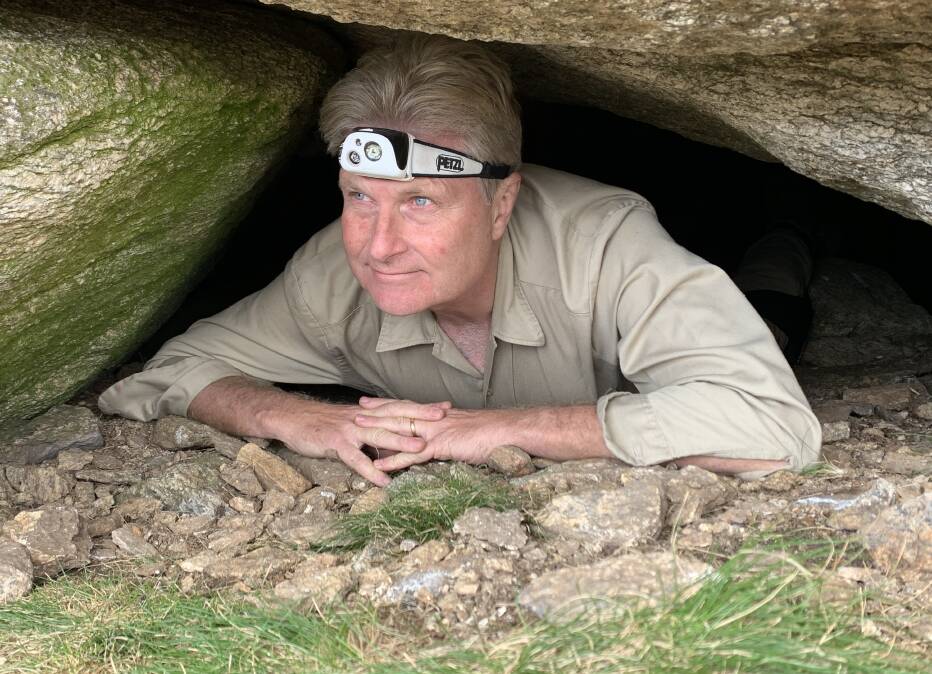

I quickly contacted Dr Eric Warrant, an Australian biology professor at Sweden's University of Lund, who has previously taken me on field trips into the mountains in search of bogong moths (Secrets of the Bogong, March 8, 2020). "Yes, we are really encouraged by the large numbers of migrating bogong moths now flying into the northern Kosciuszko National Park," says Warrant. "From our observation post at Mount Selwyn, we have recorded countless thousands of moths on their way to higher elevations on the Main Range." Great news.

Dr Peter Caley, a senior research scientist at CSIRO who has been researching the moths in the Brindabellas for nearly a decade, and who has just returned from a field trip to Mt Gingera on the ACT/NSW border, has even better news. "They are back this year in numbers pretty close to pre-drought," he says. You little ripper.

This is particularly encouraging news, especially as in 2019, at the height of the last drought, Caley observed "a 50-fold reduction in moths at Mt Gingera". Last year, the observations were even more depressing with not a single moth observed aestivating at Mt Gingera, nor at their other regular summer hangouts in Namadgi National Park, including Mt Gudgenby.

To give the moths an extra helping hand in their recovery in the Brindabellas, last week park rangers installed a special metal gate at the entrance to one of the moth's aestivation sites on Mt Gingera.

The "moth gate" is designed to prevent feral animals such as pigs, which Caley's infra-red cameras have in previous years captured venturing inside the cave to feast on the moths, while at the same time allowing the moths to fly in and out. Ingenious but simple.

A spokesperson for NSW National Parks Service says protecting the bogong moth's habitat "is part of a wider effort to conserve threatened species, including feral fox and pig control".

Professor Ken Green, an alpine ecologist at the ANU who has been documenting the bogong moth's annual aestivation on the main range in Kosciuszko National Park for more than 40 years, is encouraged by the news that the moths are returning this year, but he's not yet popping the champagne corks.

"If the numbers were as low this year as last year, then we would have been looking at the distinct possibility of bogong moths becoming extinct but thankfully the signs this year are so far looking good.

"Although there are reports that many are on their way, they haven't yet reached the caves on the Main Range in great numbers, so let's wait and see how the migration pans out over coming weeks before getting too excited," he cautions.

I can hardly wait - I've just bought a bottle of the best sparkling wine I can find and put it on ice.

Earlier this week, while watching an in-form Steve Smith belt the hapless English bowlers around the SCG, two wayward bogong moths landed on my TV screen, the first I've seen at the Yowie bunker in years - now that's my idea of a perfect start to summer.

Have you noticed a return of the bogong moths this year? Let us know in the comments below, or email Tim: tym@iinet.net.au

Did You Know?

Although the aestivating moths lay dormant during daylight hours, at dusk, sometimes significant numbers leave the caves en masse, returning to their caves later in the night. Ken Green believes it's likely connected to the moth's need for moisture. "Especially during a hot summer, I've seen them fly out of caves early in the evening to drink at nearby waterholes, before returning to the caves."

Apart from foxes and pigs, Peter Caley's cave cameras in the Brindabellas have also recorded ravens, currawongs, cats, mice, antechinus, lyrebirds, microbats, and even inquisitive humans.

Five things you didn't know about bogong moths

Timeless treasure: Among the highly productive pastures of the 1200-hectare Uriarra Station just to Canberra's west is an area of exposed granite about 30 metres long by 10 metres wide. This fenced-off area is known as the "Uriarra moth stone", a significant site where Indigenous people historically feasted on bogong moths, a delicacy they would travel from far afield to collect. Women would heat up the stone while the men trekked high into the hills each summer to collect the moths.

Archaeological find: In February 2021, cooked bogong remains were found on 2000-year-old grinding stones in Cloggs Cave, near Buchan in the southern foothills of the Australian Alps. These are regarded as the oldest archaeological evidence on the planet of humans eating insects as a food source.

Political pundits: A 2005 report by the Parliamentary Library confirmed Capital Hill formed a "giant light trap" for bogong moths. This was realised in 2013, when in September of that year unsuspecting staff at Parliament House found bogongs in coffee mugs, desk drawers and even in their hair and clothing. As a result, two-thirds of outside lights were turned off at night, and exhaust and air-conditioning vents were secured to thwart the moths.

Prolific breeders: Each female bogong moth can lay up to 2000 eggs.

Moth tracker: Zoo Victoria has developed a website where anyone along the bogong moth migration route, including in Canberra and surrounds, can help scientists track them by logging their sightings. See swifft.net.au/mothtracker/

WHERE IN CANBERRA?

Rating: Hard

Clue: For the "live ones"

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and address to tym@iinet.net.au. The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday November 26, wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

Last week: Congratulations to Anthea Bollard of Hughes who was first to recognise last week's photo as the entrance to the crypt at St John's Church in Reid. Anthea just beat many other readers to the prize, including Harold Koch of Reid, Gail Robertson of Queanbeyan, and Len Goodman of Belconnen. Meanwhile, Bente Pedersen of Campbell reports, "My husband and I often walk around the church and find the outside beautiful, just like the many birds that we see there."

The clue relating to the flood referred to the church's first Reverend, George Gregory, who drowned in the flooded Molonglo River in the flood of 1851. According to Anne Claoue-Long in Rural Graves in the ACT: A historical context and interpretation (October 2006), "On 20 August 1851, when on a return journey to his home in Canberry after visiting parishioners in the mountainous regions across the Murrumbidgee, he could not be dissuaded from trying to cross the flooded Molonglo River." Apparently, Gregory was anxious to return to study for his final exams and had already been delayed a week by heavy snow and rain. Although a strong swimmer, the cold water and strong current was too much for the 25-year-old and he was only a few metres from the north bank of the river when he threw up his arms and sank. His body was recovered three days later, and he was buried at St John's on August 29. His grave, within the Campbell family vault, was originally near the east wall of St John's but when the church was enlarged in 1872, the extension covered the vault, thereby creating a crypt.

Special note to eagle-eyed Jessica Kirsopp who noticed I'd inadvertently referred to 1852 in the clue. Poor Reverend Gregory actually drowned in the flood of 1851. In 1852 another disastrous flood struck the region and the swollen Murrumbidgee River raced through the ACT and onto Gundagai where on the night of June 24, a "wall of water" killed 89 people, making it Australia's deadliest flood.

CONTACT TIM: Email: tym@iinet.net.au or Twitter: @TimYowie or write c/- The Canberra Times, GPO Box 606, Civic, ACT, 2601

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.