These candidates are back in the ring to prove that 2018 wasn’t a singular “year of the woman.”

by Megan Kimble

September 2, 2019

Early on November 7, 2018, Gina Ortiz Jones drove home after conceding to U.S. Representative Will Hurd, a Republican from Texas’ 23rd Congressional District. A first-time candidate, Jones had outraised the sitting congressman by more than $1 million, but it hadn’t been enough to sway the swing district, which sprawls from San Antonio to El Paso along 820 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border. At 2 a.m., she got a call from her campaign manager—maybe she hadn’t lost. With all precincts reporting, Jones was up by nearly 300 votes. Although Hurd declared victory the next morning, she withdrew her concession and went about making sure that every provisional, military, and mail-in ballot was counted.

Nearly two weeks later, down by 926 votes, Jones conceded again.

All our investigations in one place. Sign up for our longform email:

“Nine hundred and twenty-six votes. I got the tattoo right here,” she says, joking, when we meet for coffee at El Rodeo de Jalisco, a colorful taqueria on San Antonio’s far West Side. A first-generation American, Jones was raised in this neighborhood by a single mom, attended public school down the street, and went to Boston University on an ROTC scholarship, eventually serving in Iraq with an Air Force intelligence unit.

“As a product of this neighborhood, I’ve been able to serve my country and get a great education only because my community and the country invested in me,” she says. In January, she told supporters she would likely run again. “There’s so much at stake. Knowing that, you can’t not be in the fight.” (In August, Hurd announced he would not seek re-election.)

She’s not the only woman who’s back for a second round.

In April, MJ Hegar, who got within three points of defeating U.S. Representative John Carter, an eight-term incumbent in a deep-red district north of Austin, announced she would challenge U.S. Senator John Cornyn. Julie Oliver, who lost Texas’ 25th Congressional District to three-term Republican Roger Williams, despite cutting a 21-point spread down to just under nine, is also running again. So is Kim Olson, the Democratic challenger who lost to Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller. This time she’s running to represent Texas’ 24th Congressional District, which spans the suburbs of Dallas and Fort Worth.

At least six Democratic women who lost their bids for the Texas Legislature in 2018 are running again in 2020, says Monica Gomez, the political director at Annie’s List, a political action committee that supports progressive women running for state and local office in Texas. Two more are coming back to run for different seats. “We haven’t seen this kind of rededication to running again in Texas since Annie’s List was founded in 2003,” Gomez says. She estimates that in the organization’s history, a total of 10 candidates have run again after a loss. “So eight in one cycle is a very large increase.”

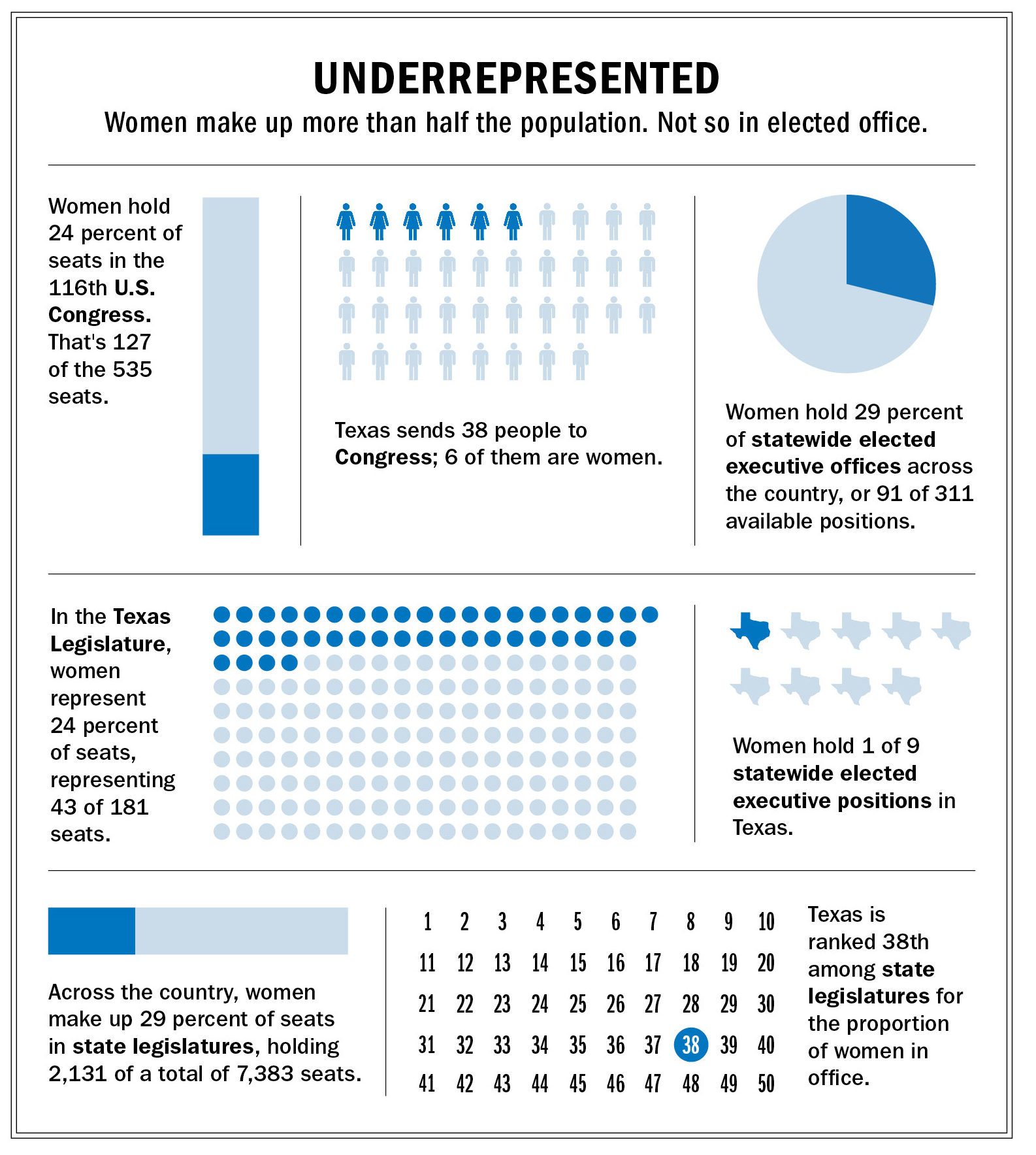

The record-breaking number of first-time female candidates who ran for office in 2018 led to a record-breaking number of first-time female officeholders: 127 women now serve in Congress, the most ever and a 23-seat increase from 2017. Despite these gains, women remain grossly underrepresented in public office at every level. Women hold 24 percent of seats in the 116th U.S. Congress and 29 percent of statewide executive positions across the country. Texas sends 38 people to Congress; in 2019, only six of them are women. In the Texas Legislature, women hold 43 of 181 seats, or 24 percent—five points lower than the national average.

Why are women persistently underrepresented in politics? Over the past decade, a body of research has established that when women run, they win elections at the same rate as men. Melanie Wasserman, an economist at UCLA who studies occupational segregation by gender, wanted to learn more. So in 2018 she analyzed the political trajectories of more than 11,000 candidates over two decades in local California elections, focusing on how candidates responded after losing an election. She found that women were 56 percent less likely than men to run again after a loss, noting what she called a “gender gap in persistence.”

“If I make the assumption that the candidates who drop out have similar chances of winning as those that run again, then the gender gap in persistence can explain quite a lot of the gender gap in officeholding,” Wasserman told the Observer. “It would increase female representation among officeholders at the local level by 17 percent.”

In other words, perhaps we should be paying more attention to the losers—the women who run, lose, and choose to run again.

“I had something up on the wall of our campaign office that said, ‘We have not lost if we got every vote, raised every dollar, talked to every person we can,’” says MJ Hegar. A combat veteran, Hegar sued the U.S. Department of Defense in 2012, charging that the Ground Combat Exclusion Policy—which prevented women from serving in 238,000 positions, a fifth of the armed forces—was unconstitutional. After her campaign ad “Doors” went viral last summer, racking up 3 million views on YouTube, she outraised Carter, bringing in more than $5 million to his $1.8 million. The influx of cash from across the country—Hegar didn’t accept money from corporate political action committees—helped her narrow a 22-point margin to three points, or 8,000 votes. Her success helped down-ballot races, engaged voters, and showed that even traditionally Republican parts of Texas could be competitive. “We forced our congressman to stop legislating like he was safe,” she says.

After the race, she returned to work—joining Hippo, a prescription drug–discounting company, as chief patient advocate—and settled back into life at home with her husband and two sons. She had no plans to run again. “Jude, my oldest, said to me right before the election, ‘When are you going to stop being MJ for Texas and start being my mommy again?’ It broke my heart,” she says. But in December, she says, he asked her: “When are you going to run for Congress again?” She told him she wasn’t planning to run, and he insisted that she should. “He said, ‘I want you to protect me.’ That was probably the first moment that I was like, OK, I’m going to have to do this again.”

Instead of challenging Carter again, Hegar decided to run against Cornyn. “It was all about, where is the urgency?” she says. A powerful three-term senator with wide-ranging influence and very deep pockets, Cornyn won’t be easy to beat. But Hegar is undaunted.

She learned a lot in her first race—how to pace herself, hone her message, protect time with her family. “It’s the difference of flying into combat the first time: I knew intellectually what to expect, but until you have your hands on the controls and people are shooting at you and the dust is flying and patients are screaming in the back, you don’t really know what to expect,” she says. “So when you go back the next time, you’re a better pilot. It’s muscle memory.”

Most candidates, male and female, run better races their second time, often benefiting from the name recognition, volunteer networks, and donor support they built the first time around. “I see people who remember me from the last cycle and they say, ‘You’ve grown so much,’” says Joanna Cattanach, who ran in 2018 to represent a slice of central Dallas in the Texas Legislature. “Sometimes I wonder: Was I really that bad?”

Cattanach, who once worked as a reporter covering Texas politics for the Dallas Morning News and Fox News Latino, came within 220 votes of beating Representative Morgan Meyer, a two-term Republican from University Park. (The last Democrat to run in her district lost by 21 points.) Despite the high cost of campaigning—on her marriage, her two young children, her finances—she couldn’t walk away from 220 votes. “I didn’t run just to see if I could do it once and that’s it,” she says. “I really cared about the issues. Those issues didn’t go away when the election ended.”

On a sweltering Friday evening in July, hundreds of people gather on the south lawn of the Texas Capitol. Dusk gathers in brilliant color across the sky as speakers stand behind a lectern on the Capitol steps and condemn the treatment of immigrant children in Texas detention centers. People listen, sitting on blankets or perched on the curbs, some holding signs: “Keep the immigrants, deport Trump.”

Julie Oliver stands on her tiptoes to reach the microphone. “We have to overhaul our immigration system to reflect the true values of our country,” she says. “It all starts by deciding who’s going to represent us. That’s why I’m running for Congress, to serve and represent you.”

After Oliver lost to Roger Williams in 2018, she took a break from all things political. “I honestly had to grieve. I felt like I let people down,” she says. Emotionally and physically exhausted, she didn’t plan on running again. Oliver took a new job as vice president of finance at Notley Ventures, a social impact investor in Austin.

But in December, when a federal judge in Texas ruled that the Affordable Care Act was unconstitutional, Oliver remembered why she’d decided to run in the first place—to fight for a law that benefits millions of people, including her 22-year-old son, who started life in the neonatal intensive care unit and was diagnosed with a heart condition when he was 6. “I call him the walking preexisting condition,” Oliver says.

In April, she announced that she was running again and started calling people who had donated to her first campaign, those who had helped her raise $645,000 without accepting corporate PAC money. “I got absolute radio silence from some donors,” she says. One donor told her he felt burned by 2018, by all the high-profile Democrats who didn’t make it across the finish line. “Texas is in play now! How can you feel burned?” Oliver says. “You have to look at this as a long game. Anyone who thinks we are going to pull a rabbit out of a hat is not being realistic.”

It is a well-documented fact of campaigning that male candidates raise more money than female candidates. A 2018 NPR analysis found that Democratic men running for Congress in the 67 most competitive districts raised an average of $500,000 more than Democratic women. “Men can ask for money and people are like, ‘Here, let me open my checkbook,’” Oliver says. “A woman is asking for money and it’s almost distasteful. It’s so challenging to get a man to listen to you and be receptive.”

“I can literally look and see what someone has given to a man, as they are on the phone giving me a quarter or half of it,” Cattanach says. “That shocked me two years ago. Now, pshhh. I ask [for more] because I know it’s going to happen.”

When men hold the overwhelming majority of elected offices, donors and voters alike still expect candidates to be male. Wasserman, the UCLA economist, looked at school boards, which tend to have more women, and city councils, which tend to skew male, and found that “the gender gap in persistence seems to go away in offices with higher female representation,” she says. “If there’s a higher-female-representation office, then voters have better information regarding female candidates: what it’s like to observe a woman in office, their capabilities and so on.” It’s not that voters have a “distaste for women,” she says. It’s that they simply don’t have enough information about women in public office because there aren’t very many women in public office.

It’s a vicious cycle: Politicians can only be male because they have always been male. Wasserman prefers to frame it differently. “You can imagine if that the female representation among officeholders increased, then this would lead to a virtuous cycle in which it would improve the environment in which women were running and therefore encourage more women to run for office,” she says.

The surge of Democratic women who ran in Texas in 2018 helped to rebuild a party infrastructure that had languished for nearly three decades. People stepped up to become precinct chairs. Volunteers registered voters and learned how to block-walk. Candidates hired and trained staff. When she was running for agriculture commissioner, Kim Olson brought nearly 70 candidates to Fort Worth for a daylong training focused on the logistics of campaigning while female: staying safe when block-walking, collaborating with other candidates, talking to the press. “We built infrastructure in 2018,” she says. “Now we’re going to really flex it.”

This awakening has yet to reach the Republican Party. Just 142 Republican women ran for U.S. Congress in 2018, compared with the 387 women who ran as Democrats, according to the Center for American Women in Politics. In Texas, only 15 Republican women ran for the Legislature, compared with 66 Democratic women. “Getting out there and supporting, recruiting, and training female candidates to run for office has not been a priority for the [Republican] party, whether it’s at the federal level or the state levels,” says Jennifer Carroll, who co-founded Maggie’s List in 2010 to support fiscally conservative women running for Congress—a counter to the influence of Emily’s List, a nonprofit founded in 1985 to elect pro-choice Democratic women.

“If I were a young woman today, I would look at both parties and see one that was incredibly welcoming and begging me to participate and one that looks like it couldn’t care less,” says Jenifer Sarver, who founded Sarver Strategies, a public relations and consulting agency in Austin. In 2016, Sarver watched the presidential race with growing concern. A lifelong Republican, Sarver had worked in Washington, D.C., as an adviser to then-U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison and as the deputy director of public affairs in the U.S. Department of Commerce under George W. Bush. She wasn’t a Democrat—but she certainly wasn’t going to vote for Donald Trump. “I was concerned about the direction of the Republican Party and the tone and tenor of our rhetoric,” she says.

So when her congressman, Representative Lamar Smith, R-San Antonio, announced he was retiring, she decided to run. “I thought it was important for people to see a center-right Republican,” she says. It was a crowded primary, with 18 candidates on the ballot. Sarver was the only woman to crack the top five; the seat ultimately went to Chip Roy, the former chief of staff to U.S. Senator Ted Cruz.

Sarver was supported by the Republican Women for Progress (RWFP), a nonprofit founded in 2016 as Republican Women for Hillary that’s now focused on supporting Republican women running for office. It’s a steep climb. In December 2018, the group did a national survey of Republican primary voters and asked: Are you alarmed that only 13 Republican women hold seats in the U.S. House of Representatives? “And 71 percent of those voters said that they were not alarmed at all,” says Jennifer Pierotti Lim, RWFP’s co-founder.

What do you do when a majority of Republican voters don’t care about electing women? Lim and Sarver both pointed to the Republican Party’s distaste for so-called identity politics. “The fact that we don’t like to segment ourselves into caucuses based on our gender or [race] means that we have allowed the status quo to maintain, and the status quo has been white male,” Sarver says.

Laquitta “Sarah” DeMerchant was at work one day in 2002 or 2003 when her manager pulled her aside and told her that she was earning less than her male colleagues. She’d recently earned her MBA from the University of Houston-Victoria and was working in Houston at one of the largest software companies in the world. When she asked how much less she was earning, DeMerchant learned the gap spanned nearly $40,000.

“I was mortified,” she says. “I did everything they said you’re supposed to do. I negotiated pay, I researched how much I was supposed to make.” She dedicated herself to closing the gender wage gap, speaking at conferences and colleges and developing an app to help increase salary transparency. Then, in 2014, she read a report that found the time it would take for women to reach wage parity with men had actually increased from the previous year. “I was devastated,” she says. “I thought, the men have had their shot to end this. This is something that is fixable if, frankly, women have a seat at the table.”

In 2016, DeMerchant ran to represent Texas’ 26th Legislative District in suburban Houston, where she lives with her husband and two kids. She lost that election by almost 11,000 votes. She ran again in 2018 and lost, but narrowed her margin to just over 3,000 votes.

She says she understands why candidates quit after a loss. Managing a campaign while working full time can be overwhelming for both the candidate and her family. “Most of the time, it’s a two-person block-walking team, my husband and I,” she says. And, she says, she struggled to get donors to take her—a political newcomer—and her race seriously.

If it’s hard for women to fundraise at the same rates as men, it’s even harder for women of color, like DeMerchant. A study from the Center for Responsive Politics found that black female candidates running in 2018 raised 55 percent less money than the average white female candidate. For women of color, “the standards of viability are even higher, appearance is all the more scrutinized, and ‘relatability’ is tougher to achieve,” wrote Judith Warner, a fellow for the Center for American Progress, in a 2017 report.

But giving up isn’t an option DeMerchant has seriously considered. “These problems just aren’t being addressed,” she says. “I can’t stop, because that means I will accept the status quo, and the status quo is unacceptable to me.”

So she’s still out there, knocking on doors and talking to voters about her 2020 campaign.

Top photo by Sarah Wilson.

Read more from the Observer:

- Expecting Care: How Texas is failing foster kids and contributing to an alarming teen pregnancy rate.

- Forgotten in the Fields: Labor trafficking hides in plain sight across Texas, disproportionately affecting the thousands of farmworkers who visit the state on H-2A guest worker visas.

- Dammed to Fail: An Observer investigation finds that unregulated dams across Texas are increasingly failing—putting people and property in jeopardy.