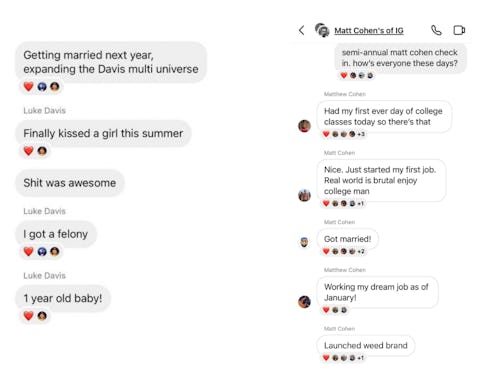

Last month, journalist Matt Cohen tweeted about his years-long Instagram group chat comprised of fellow Matt Cohens, which he calls “the most wholesome thing I’m a part of.”

In the chat, one Matt Cohen shared that he “had [his] first day of college classes today,” to which a Matt Cohen responded “Nice. Just started my first job. Real world is brutal enjoy college man.”

“Got married!” and “Just started my dream job!” chimed in fellow Matt Cohens. Another Matt Cohen announced he had launched a weed brand. The Matt Cohens, who have turned a shared name into an informal online club, planned a Zoom Happy Hour to catch up.

Your name clones usually lurk around you like a shadow. You get their junk mail, their emails, their Google results; glimpses of their intimate moments via their digital ephemera. They are strangers — but they don’t have to be.

Hello, our name is...

Around the world, people are maintaining multigenerational, global friendships with their same-named counterparts — Jake Wright, William Hodgson, Jordan DaSilva, and Josh Brown, to name a few. Sometimes, name twins commiserate about shared experiences: a sixteen-member Council of Aaron Johnson chat laments about the viral Key and Peele sketch that introduced the now-inescapable A-A-Ron nickname. Perhaps the best, or at least the most publicized, example of same-name camaraderie is the Josh Fight, when a group chat of Josh Swains organized an April 2021 meeting in Lincoln, Nebraska to fight for the “right” to the name. More than 900 Joshes showed up.

The Paul O’Sullivan Band has four members with one thing in common: the name Paul O’Sullivan. The quartet materialized after Baltimore Paul started “indiscriminately adding other Paul O’Sullivans on Facebook” and realized that a few different Paul O’Sullivans were musicians. These days, a quartet of Paul O’Sullivans, who hail form from Baltimore, Rotterdam, Manchester, and Pennsylvania, have come together to form a bona fide musical group.

Since its early days, the social internet has been lauded as a way for niche interest groups to connect, and name twins are no exception. A chat titled “Council of Bens” hosts 2500 Benjamins and Bens, and when one Ben caught wind of a similar group chat of Sydneys, he created a chat just for people named Sydney or Ben, which has been going strong for months. Chris Lenaghan added 7 other Chris Lenaghans to a chat, and soon he had same-name friends from Ohio to Belfast to Birmingham. In a Josh Kaplan group chat on Twitter, fellow Josh Kaplans use the chat to congratulate each other on achievements and awards: “A win for one JK is a win for all.”

Samuel Stewart, a 19-year-old Exeter student living in London, formed an Instagram chat of fellow Samuel Stewarts after reading about the Josh Fight. For a few weeks, they chatted about their days; older Sam Stewarts gave advice to younger Sam Stewerts. “They seemed to take me under their wing as if I were a younger version of them,” said a 19-year-old Sam Stewert when we talked on the phone. But the chat went awry when one Samuel Stewert started asking for money. “I felt a bond with the fellow Samuel Stewarts, but the name connection wasn’t quite strong enough for me to start giving away my college fund,” Sam told me.

“They seemed to take me under their wing as if I were a younger version of them.”

The chats aren’t strictly social — sometimes, they’re the most practical way to sort through same-name mixups. Will Packer, a strategist in New York, recently used the Will Packer chat to see if any of his name brothers had been contributing to his inbox clutter. “Any of you from Queensland?” he asked. “Someone tried to create a PlayStation account with my email.”

College student Nolen Young says, “I once created a Facebook Messenger group chat with everyone I could find on Facebook with my exact same name, spelling and all. There were only two other people. One of them considered giving me a job, and the other was an old man who started commenting on all my photos. I've messaged the former a few times because he owns every domain name and email I've ever wanted, and he keeps telling me I can only have them when he dies.”

It’s easier than ever to connect with same-name pals today, but the uncanny allure of name clones predates social media. Tahnee Gehm, an artist and animator based in L.A., organized a Web 1.0 catalog of Tahnees when she was a teenager.

“My dad was into computers and he got me a URL with my name,” she says. “I built an atrocious ‘90s website in 2001 as an eighth grader, and I started getting messages from girls all over the world named Tahnee.”

To catalog her new pen pals, she created a “Hall of Tahnees” webpage with a photo, bio, and hometown for every Tahnee she could find. The site’s “Tahnee-only area” was a “weird, unique club.” Once, she says, a singer from the band Hanson used the website to track down a girl named Tahnee he’d met at a concert. And the Tahnee bond has lasted decades: Tahnee Gehm has maintained a long-distance friendship with Tahneé Engelen since they were in high school. A few years ago, Gehm spent two weeks visiting Engelen in Paris, where she works as a neurobiologist.

“It’s nice to know that my name buddy is living my alternate life and absolutely killing it,” she told Input over the phone.

Sometimes, all it takes to spark a friendship is a similar email address. Seth Capron met an older Seth Capron after noticing their similar interests based on the emails he mistakenly received — soon, they realized their physical resemblance, too. These days, the older Seth jokes that he could pass on his career. “I was actually considering that as I move into retirement, the Younger could just carry on in my former role of Seth Capron, affordable housing consultant,” said “Seth the Older.”

Name buddies sometimes have a parasocial relationship with each other’s digital footprint. As a kid, Chris Lenaghan found online videos of a different Chris Lenaghan doing wheelies and “cool BMX shit” and immediately told all his friends that it was him in the videos. Years later, thanks to a big group chat, Chris Lenaghan met the BMX trickster, who he now calls “Ohio Chris,” and they ended up becoming close friends.

The chats don’t always advance beyond acquaintanceship, though. Evan Quigley, a University of Florida student, says that the Evan Quigley group chat is “more like a running joke than true friendship.” (The Evan Quigleys, bonded by name alone, proclaim unconditional public support for one another by commenting “way to go, Evan Quigley” on each other’s posts).

People with uncommon first names can bond over shared experiences — mispronunciations, playground taunts, and misspellings. More than a dozen Zaviens have come together via Snapchat. “None of us had ever talked to another Zavien,” one Zavien told Input. And a 14-member-strong “Council of Ethyns” chat, which started on Instagram in 2019, is mostly dedicated to tongue-in-cheek malice toward Ethans (with an “a”). They also just pop in the chat to say “love you Ethyn” a lot.

Still, the unlikely connections evoke nostalgia for a simpler internet, less cluttered with surveillance and corporate interests, where people went to meet new friends. Occasionally, wholesome chance online encounters remain. “Text door neighbors,” for example, or people with phone numbers one digit apart, show how easy it is to stumble upon an unlikely friend. Most notably in the wrong-number-gone-right stories, the duo Wanda and Jamal, whose viral wrong number ordeal has led to a six-year-long-and-counting Thanksgiving tradition, is now set to be featured in an upcoming Netflix movie.

It’s a big world out there — lots of Matt Cohens, more Alex Stewarts, and even more James Smiths — and your name buddies have never been easier to befriend. And I think that’s beautiful.

But just because we’re psychologically inclined to like our own name, doesn’t mean you’ll have a guaranteed connection with your name clones. Just ask Kelly Hildebrandt and Kelly Hildebrandt, the couple that tied the knot a year after they’d met when name-searching on Facebook and then, four years later, called off the marriage due to irreconcilable differences. It’s not all in a name.