On the day of her uncle’s funeral in 1995, Jane’s life changed forever.* That was when she found out her uncle Edward, a person with haemophilia, had been infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from the treatment he was taking for his condition.

Adding to the family’s pain, the stigma that surrounded HIV and the disease it causes, Aids – because of its association with homosexuality and drug addiction – meant they kept the cause of Edward’s death to themselves. At the same time, they knew that Jane’s father, Roy, also had haemophilia and had been receiving the same treatment as his brother.

A rare genetic condition means that throughout their lives, people with haemophilia – of whom there are around 6,000 in the UK – must seek medical care when they bleed because one of their key blood clotting proteins, factor VIII or IX, is either partly or completely missing. In the 1970s and 80s, a new treatment to give people with haemophilia their missing protein using concentrated blood plasma was seen as potentially life-changing. In fact, it dealt many of them a death sentence.

Read more: Infected blood scandal – what you need to know

The factor VIII concentrate was supplied by US pharmaceutical companies. Donors were paid for their blood, and much of it came from communities at higher risk of carrying infectious disease, including drug addicts and people in prison.

Gradually, haemophilia communities on both sides of the Atlantic noticed some among them were getting sick from a mysterious new virus. The first death of a person with haemophilia from Aids occurred in the US state of Florida in January 1982. The following year, both the Lancet medical journal and the World Health Organization published recommendations that people with haemophilia should be warned of the new health risks they faced – which also included infection with hepatitis C, a potentially deadly virus that affects the liver. Yet no such warnings were given.

While Edward soon became ill with HIV, Jane’s father did not reveal his hepatitis C infection, even to his daughter, until she was 18. He later died from liver cancer. Jane recalls:

My dad died ten years ago now – it’s nearly his anniversary. When he died, I went back to the doctors and said: ‘Do you think the hepatitis has caused the issues with his liver?’ The room fell silent. I didn’t need an answer. Their body language, their silence, told me everything I needed to know.

Jane says her father’s mistrust of doctors and medical advice meant he avoided the factor VIII treatments unless he really needed them, and “in some respects that prolonged his life” by limiting the amount of infected concentrate he was subjected to. One of Jane’s earliest memories is of him refusing to go to hospital, despite intense pain from a bleed into his joint. But each of these bleeds caused new damage to Roy’s body, resulting in increasing pain and disability as his life went on.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

The societal stigma surrounding Aids meant many people with haemophilia lived with their infections in silence – assuming, that is, they were aware of their diagnosis. Another shocking aspect of this global contaminated blood scandal is that often, the victims weren’t being told the truth themselves.

During a recent conversation with her mother, Jane discovered that, for a long time, her father and uncle had not been told of their infections by doctors who by then knew about the problem of contaminated blood, leaving her family at risk of catching hepatitis C and her uncle at risk of passing on HIV. In her father’s case, it was only when, in 2004, he was notified by the NHS that factor VIII concentrate carried a very small risk of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) – a rare and fatal brain disease better known in the UK as “mad cow disease” – that he was informed this was because of his hepatitis C infection. Jane recalls:

My dad was like: ‘Excuse me, what?’ It was the same for my uncle Edward. There was no formal notification [of his HIV diagnosis] – the doctors and nurses just suddenly started wearing a lot of blue gloves around him.

Jane’s own story encapsulates the multigenerational impact of the infected blood scandal, which I (Sally-Anne) have researched with colleagues at the University of Gloucestershire. Jane carries the haemophilia gene, which is passed from mother to son with a 50% chance, and one of her two sons has haemophilia. Jane recalls the moment she told her father Roy, who was already infected and unwell with hepatitis C, that she was having a son:

We bought a blue romper suit and I took it home and gave it to my dad. He opened the bag and just threw it back at me. He went: ‘No, I can’t deal with this.’ And that’s not okay – he should have been proud, excited.

When Jane’s son was born, it was difficult for the family to face up to the treatments for haemophilia that would be a regular part of his life. She recalls her father “holding our newborn child, begging me not to ever let him have these treatments”.

‘A criminal cover-up on an industrial scale’

The infection of people with haemophilia is just one aspect of the global contaminated blood scandal – which in the UK is regarded as the “worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS”. In total, around 30,000 NHS patients were infected with HIV and hepatitis C between 1970 and 1991, either through contaminated blood products such as factor VIII and IX or blood transfusions during surgery, treatment and childbirth.

Recently Sam Roddick, daughter of Body Shop founder Anita Roddick, wrote in the Sunday Times about a “chain of decisions that were morally unlawful” which led to her mother contracting hepatitis C from a blood transfusion after giving birth to Sam in 1971. The blood used for transfusions, which is donated for free in the UK, was not routinely screened for HIV until 1986 and hepatitis C only five years after that.

One person still dies every four days in the UK as a result of having received contaminated blood. An estimated 26,800 people became infected with hepatitis C and 1,243 with HIV. Of those infected with HIV, 380 were children – more than half of whom have died. Following earlier inquiries by Lord Archer and the Scottish government (which was branded a “whitewash” by some of those affected), the UK’s infected blood public inquiry was finally announced by the then-UK prime minister, Theresa May, in July 2017. She called the scandal an “appalling tragedy which should simply never have happened” – adding:

Today will begin a journey which will be dedicated to getting to the truth of what happened and in delivering justice to everyone involved.

A few months earlier, in his final speech as an MP in April 2017, Labour’s health secretary Andy Burnham had described the scandal as a “criminal cover-up on an industrial scale”, suggesting there might be a case for corporate manslaughter charges. Of people like Jane’s father and uncle with haemophilia, Burnham said:

The Department of Health, and the bodies for which it is responsible, have been grossly negligent of the safety of people in the haemophilia community over five decades.

Like so many family members, Jane’s life plans as a young woman were turned upside down by her father’s illnesses. One of hundreds of witnesses heard during the seven-year inquiry, Jane wants the long-awaited final report, which will be published on May 20, to recognise the suffering of all those affected by the scandal, explaining:

I don’t think there’s been any real recognition for the families and what they’ve been through. People and families in particular have been destroyed by this. I was at university trying to be a teacher but dropped out, much to my university’s dismay. I wanted to be at home to stay with dad. There’s a generation of us that have lost our families – they call us ‘the fatherless ones’.

Many of those affected by the scandal blame the UK government and NHS trusts who they claim knew but did not share information about a potential infection risk with those taking the new treatment.

Deaths, loss, and continued denial

In January 1982, one of the UK’s leading experts in haemophilia, Arthur Bloom, co-wrote an infamous letter to haemophilia centres throughout the country, telling them that it was very important to ascertain whether a new American blood product already being given to people with haemophilia in the UK showed reduced levels of hepatitis C. “As far as we know,” he wrote, “the products have been subjected to a heat treatment process”, adding:

Although initial production batches may have been tested for infectivity by injecting them into chimpanzees, it is unlikely that the manufacturers will be able to guarantee this form of quality control for all future batches.

This method of producing factor VIII protein involved taking large amounts of blood (up to 40,000 units) from many different people and reducing this to a concentrate that could be easily self-injected at home. Bloom suggested “the most clearcut way” of testing the infectivity of the new heat-treated product was on patients requiring treatment who had not been previously exposed to large-pool concentrates – including children.

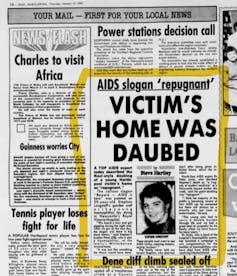

One of the children treated by Bloom himself at the University Hospital of Wales was Colin Smith, who had haemophilia and weighed just 13 pounds when he died of Aids in 1990 at the age of seven. He was a year old when he was given the factor VIII treatment, and his HIV status was confirmed at two-and-a-half. The stigma of HIV meant the family were shunned by many in their community, including having the words “Aids dead” painted on the side of their house in six-foot high letters. As Colin’s mother, Janet Smith, recently told BBC Wales:

We were known as the Aids family … We’d have phone calls at 12, one o'clock in the morning, saying: ‘How can you let him sleep with his brothers? He should be locked up, he should be put on an island’… He was three.

The same BBC investigation found evidence that Bloom had ignored internal NHS guidelines, written by his own department, that discouraged the use of the imported factor VIII treatment on children because of the risk of infection. Bloom was clearly aware of the risks when he began treating Colin in the autumn of 1983. “This wasn’t an accident,” Colin’s father said. “It could have been avoided.”

None of the young patients, known as “previously untreated patients”, or their parents knew they were part of a nationwide experiment at the time. Documents subsequently released reveal that the UK government funded some of these studies – including one of pupils at Treloar’s College, a specialist school in Hampshire with an NHS Haemophilia unit on site. Of 122 pupils with Haemophilia attending the school between 1974 and 1987, to date 75 have are reported to have died as a result of HIV and hepatitis C infections.

By 1984 – just over two years after the first death from Aids in the UK – government experts were aware that people receiving American factor VIII blood concentrate were at risk of HIV infection. Yet despite the mounting evidence, denials and silence continued well into the 1990s.

Trevor Graham, one of the hundreds of contributors to the infected blood inquiry, spoke to us about his father, who had haemophilia and died in 1991 when Graham was only 13. “We had no idea at the time he had died of Aids,” Graham explains. “We thought he died of a brain haemorrhage, as that was what the doctors treating dad at the Manchester Royal infirmary told my mother.”

Yet for the four years before his death, Graham’s father had been unable to work and sought the support of the Macfarlane Trust, a discretionary grant-making trust that was set up and funded by the then-Department of Health to “alleviate the financial needs of those haemophiliacs infected with HIV through contaminated NHS blood products”, and also their families. Graham says:

It is heartbreaking to read the letters my dad wrote requesting assistance, one of which states that he was concerned about Christmas presents for myself and my sister. In that letter, he stated he was HIV positive and couldn’t work as a result of his infection.

Despite there being no reference to HIV on their father’s death certificate, Graham says rumours soon spread around their school and local community. Once again, the legacy of this infection continues to affect following generations:

My sister and I were bullied at school. People said that our dad was gay and that he died of Aids. Mum became agoraphobic when I was 13 and was advised to see a psychiatrist, but in her grief she refused. I was suffering from hidden anxiety as a young teenager and developed a stutter. The anxiety and bouts of depression have never left me since my dad passed away. Even 30 years later, I still struggle with my mental health.

A monster arrives

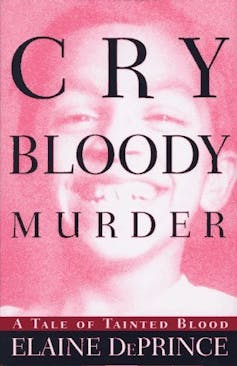

“The monster arrived as a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” writes Elaine DePrince in her moving memoir about the contaminated blood scandal in the US, Cry Bloody Murder. The monster was factor VIII concentrate created from blood infected with HIV and hepatitis C. Three of her sons had haemophilia; all three would die slow, painful deaths due to Aids, having been infected by the treatment that was meant to help them lead normal lives:

When Teddy died, he was the last of our three boys with hemophilia and Aids to leave us. He was the last of our three little boys, our three musketeers … He was 24 years old, and it seemed like he had lived forever with Aids.

In the book, DePrince, whose family were living in a suburb of Philadelphia, describes an earlier conversation with her husband when a warning label finally appeared on vials of factor VIII concentrate. She pointed out there was no need to worry, as all three of their sons with haemophilia were already infected with HIV.

As their youngest son Cubby’s condition worsened, he wrote a list to ease his concerns about other children getting Aids, at a time when it was untreatable, entitled “64 reasons why you do not want to get AIDs”. These included:

If your liver gets too big, you have to sit half-lying down and half-sitting up. Then it’s hard to paint your model airplanes because the paint drips on your stomach.

The battle to gain justice took DePrince from writing letters to campaigning for a change in the law and writing a book to explain the reality of the contaminated blood scandal and her family’s suffering from it. She concludes:

I cannot repress my sorrow, my pain, and my rage … The FDA [US Food & Drug Administration] failed my children. The blood-banking industry failed them. Government agencies failed them. The law failed them.

Jonathan is a haematologist in the US who comes from a family of men with haemophilia. When he was around seven years old in 1989, both his uncles were infected with HIV. One died in 1992 and the other shortly afterwards. “Our family and the haemophilia community were ravaged – we lost an entire generation. I had to watch my uncles deteriorate over the years.”

Jonathan, who also has haemophilia, grew up in a rural suburb in Illinois. He reflects on how that made getting treatment all the harder for his uncles:

It turns out that not only was there the contaminated supply that ravaged an entire generation of people with haemophilia and other severe bleeding disorders, but there wasn’t even equal access to care in the US at that time. Growing up in the Midwest, we didn’t have the same HIV therapies available on the east and west coasts of the US, where HIV research was being done. Some of the medical innovations at that time really did not penetrate the heartland of the US like it did on the coasts. So, I just had to watch my uncles deteriorate.

Jonathan himself was “only” infected with hepatitis C from his treatment. He says “that actually made me feel guilty – why was I spared [from HIV and Aids]? You know, everyone else is dying. Why should I be alive?”

The experience drove him to become a doctor in haematology, in order to try to make the experience better for other families like his:

People have been left to suffer. I grew up not knowing if I was going to live. The sad thing now, being a physician, is that HIV is such a manageable disease now.

The fight for justice

Across the world, many people have devoted their lives to fighting for justice for all those affected by the contaminated blood scandal. In the UK, groups such as TaintedBlood, Birchgrove Group, Factor 8, BloodLoss Families, Contaminated Blood Campaign, Contaminated Whole Blood UK and many others have continued the brave battles of the early whistleblowers and campaigners.

Jason Evans’ father Jonathan, who had haemophilia, was infected with HIV and hepatitis C and died in 1993 aged 31, when Evans was four. He has been campaigning for justice for his father and others for more than a decade, using freedom of information acts to reveal documents relating to the scandal. In one shocking memo from 1985, a UK government official discussed the financial implications of the fact that many people with haemophilia who were infected with HIV would soon die:

Of course, the maintenance of the life of a haemophiliac is itself expensive, and I am very much afraid that those who are already doomed will generate savings which more than cover the cost of testing blood donations.

Evans, the founder and director of the campaign group Factor 8, is leading a legal action against the UK government for more than 500 people. Their action resulted in permission to launch a High Court action to seek damages but is currently on hold pending the outcome of the current inquiry on May 20.

Evans has expressed concern that ministers are “seeking to water down” the inquiry’s strong recommendations from the interim reports. He recently told the Guardian:

What I want from the inquiry is it finally to be on the official record that what happened was entirely preventable and was motivated by unethical practices. For decades, the line from government was that this was an unavoidable accident that no one could have possibly have foreseen – that no one did anything wrong.

In November 2022, “interim” compensation payments of £100,000 each were made to around 4,000 infected people or their bereaved partners in the UK (on top of an “ex gratia payment” by the government in 1990 of £20,000 or £25,000, depending how badly a patient’s body had been damaged by their infection). But this has left many others affected by the scandal, including those who have lost their children or parents, without any compensation – along with those whose death left nobody behind to claim.

However, a recent amendment to the Victims and Prisoners Bill added a requirement for the UK government to set up a compensation scheme within three months of it passing on May 1. On May 5, The Times reported that ministers were preparing a compensation package of £10 billion minimum for contaminated blood victims; the details are to be announced after the public inquiry’s report is released.

Two court cases are in progress in the UK: the one led by Evans, and another against Treloar College by 36 former students, who claim the experiments on them breached its duty of care by giving the treatment without discussing the risks with the students or their parents. In 2023, in testimony to the inquiry, the college’s former headteacher, Alec Macpherson, admitted that doctors at the school were “experimenting with the use of factor VIII”.

Elsewhere, criminal proceedings were brought against government officials and executives in pharmaceutical companies as long ago as the 1990s, with French and Japanese officials being given prison sentences. In 1997, Bayer and the other three manufacturers of the factor VIII concentrate paid out a total of US$660 million (around £1 billion in today’s prices) to the estimated 6,000 people with haemophilia who were infected in the US.

There is also the potential for criminal charges or other consequences for those involved in the UK scandal. It is possible that those identified as responsible may be charged with gross negligence manslaughter, and, in the case of collective fault of an organisation, corporate manslaughter charges could be brought. Individuals who supplied the contaminated blood could be prosecuted for grievous bodily harm.

Campaigners often use the phrase “justice delayed is justice denied” – not least for the one person infected with contaminated blood who continues to die every three days in the UK. But the effects of this medical scandal will be felt for years and generations to come – and whatever the outcome of the inquiry, campaigners will continue to fight for justice. As Evans explained when he was nominated for an award in 2021:

I think something that fuelled our renewed campaign was a new energy, particularly from those whose parents had died. We were grown up now and we were angry. I think that energy spread to the older campaigners who had been let down by the government time and time again.

This complex, seven-year inquiry was forced to delay its final report for five months to allow the many people and organisations referenced sufficient time to respond. Some victims have found out things they did not know about their treatment. Others have called for national memorials for the victims in each UK countries – including one specifically for the children infected at Treloar College.

The inquiry has affected people in different ways. Some have felt compelled to attend every sitting. Harrowing testimony has been heard throughout – not least when Colin and Janet Smith spoke about their son Colin, the youngest person to have been infected in the UK. His father told the inquiry:

There’s no way a child should have to die the way Colin did. It wasn’t pleasant. It still affects us now. But it’s not just our son – there’s lots of children who have had to go through that … I would cope with death, but not with the death of my son. I still have trouble today; the fact that he’s in a grave on his own. The guilt will never go away.

*Some names in this article are pseudonyms, created to protect the identity of our interviewees.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Why people self-injure: ‘You have no other voice – and no one would listen anyway’

GP crisis: how did things go so wrong, and what needs to change?

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sally-Anne Wherry is affiliated with the Journal of Haemophilia Practice (editor). Members of her family are core participants in the Infected Blood Inquiry. She is a member of the Haemophilia Society and the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders. She is a member of the Women’s Equality Party and the University and College Union.

Hannah Grist does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment. The authors wish to thank all those who have taken the time to offer their stories and knowledge while awaiting the final report of the Infected Blood Inquiry.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.