They came from different places — the Bernsteins Eastern European Jewish migrants, the Atkinsons one of the earliest Black families to arrive in Chicago. And their descendants have never met. But their stories cut across Chicago history and intersect in surprising ways.

Members of these families were deeply entwined with the history of Chicago’s abolitionist movement, film and entertainment scene, transportation industry and foundational religious institutions. And they were affected in different ways by discriminatory housing practices in the mid-20th century.

The separate threads of these two families’ stories illustrate ways in which every family history is also a history of the place that is their home.

The Atkinsons: early Black settlers in Chicago

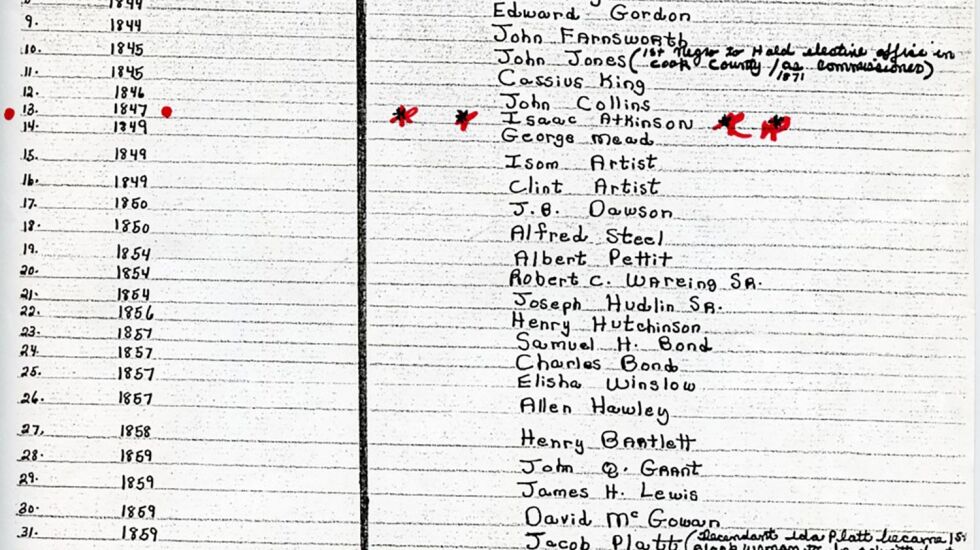

The Atkinsons were the 13th Black family to settle in Chicago, with Isaac and Emma Jane Atkinson arriving from Virginia in 1847. Their great-granddaughter Michele Madison is the keeper of the family history and provided glimpses of the Atkinsons’ 175 years in Chicago.

Emma Jane Atkinson was part of the “Big Four” — a group of abolitionist women who helped run the Underground Railroad out of Quinn Chapel AME Church, the first Black congregation in Chicago. Black people seeking freedom in cities in the North like Chicago could be arrested and sent back into bondage under the Fugitive Slave Act. Born of free parentage, Emma Jane Atkinson had some degree of protection from arrest, and this allowed her to help countless others find shelter and safety through her work, according to their great-granddaughter.

Isaac Atkinson, who was half Scottish and half Cherokee, started his own transportation company — a system of long, horse-drawn carriages, called omnibuses, that picked up passengers and took them along what were then the muddy, unpaved roads of 19th century Chicago. He used his financial success to buy 20 plots for the Atkinsons in Graceland Cemetery, which helped further establish the Atkinsons’ roots in Chicago and placed them, in death, alongside some of the city’s most prestigious families.

The Atkinsons threw parties and did business with other Black families who moved to Chicago during the mid-19th century. Eventually, an exclusive society started to form. By 1904, the families formalized this network and called it the Old Settlers Social Club.

It was made up of about 3,500 families whose members included businessmen, politicians and working-class craftsmen. The only way to become a member was to be a part of a Black family who had been in Chicago at least 30 years. One prominent member was Michele Madison’s Uncle Petie, who she says took great care in maintaining the Atkinson family reputation within the community. She says he made sure that she and her older sister Grace knew how to present themselves in public.

“My sister was actually presented to society, when there was such thing as a Negro society to which to be presented,” having her coming-out presentation when she was 16, Madison says. “Back in the day, people would introduce you to other families and try to see who was marriageable in one family to another family — very old school.”

The bonds that held the Old Settlers Social Club together began to fray as the Black population in Chicago grew by the mid-20th century to the hundreds of thousands.

For the Atkinsons, life was changing in other ways, too. In 1950, they and 3,400 other families had to move out of their homes in an area north of present-day Bronzeville to make way for the Lake Meadows housing development — Chicago’s first urban renewal project, built as part of a pilot program in which federal and state governments gave cities funds to level so-called blighted neighborhoods and build new housing.

Michele Madison was 6 when she moved into the family’s new home in Woodlawn, where she still lives today.

“I love it here,” she says. “I come down that street and my car, and I smile. … If you come in the summer, there’s flowers on the porch, and my catalpa trees have grown. And it just makes me feel, wow, that’s home. This is home to me.”

She plans to donate her home to an organization that runs Community Integrated Living Arrangements — CILA — homes,for young women with intellectual disabilities. So though there won’t be Atkinsons living there, she says, the importance of this house in Woodlawn will live on.

The Bernsteins: Early Jewish migrants to the Southeast Side

Nathan and Nettie Bernstein arrived in South Chicago in 1888 from Marijampolė, Lithuania. Like many Eastern European Jewish families then, they moved to escape antisemitism and in search of better economic opportunity in the United States.

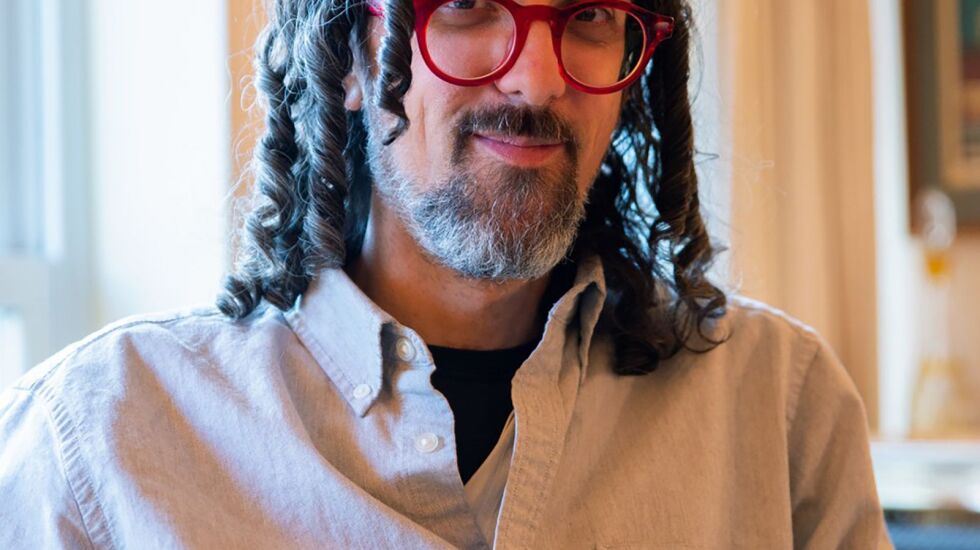

Chuck Bernstein — a grandson — and his wife Roberta Bernstein and their son Aryeh told stories of their family and six generations of Jewish life in Chicago.

Nathan Bernstein’s first job in Chicago was selling dry goods, and he was an early member of the first Jewish congregation on the Southeast Side, Bikur Cholim.

Aryeh Bernstein’s maternal great-grandparents Jacob and Sima Lesner arrived in Chicago a few years after the Bernsteins. Their son Sam Lesner was asked to write reviews about the Yiddish theater scene in Chicago. This kicked off a successful career, with Sam Lesner going on to cover film and entertainment for the Chicago Daily News through the 1960s.

In their Hyde Park living room, Roberta Bernstein displays an album stuffed with newspaper clippings and photos of her father with some of the biggest names of the day in entertainment, including Sidney Poitier, Julie Andrews and Alfred Hitchcock.

Through his work covering the entertainment scene, “His world was much more integrated than the worlds of almost anybody else in 1950s America,” Aryeh Bernstein says.

In the 1960s, not long after Sam Lesner moved the family to the Southeast Side neighborhood called Pill Hill, he started getting calls from real estate agents telling him to sell his home. Black families seeking a better life were moving from rural areas in the South to Northern cities, and real estate agents, engaging in what became known as block-busting, wanted to profit off from this.

Aryeh Bernstein says his grandfather would get calls late into the night pressuring him to sell.

“ ‘Another one moved on to the block, Lesner, you better sell now,’ ” he says his grandfather was told. “ ‘I’ll give you cash for your house. Now, if you don’t go now, you’re gonna lose everything.’”

Developers would buy these homes from white families who were willing to sell and then would rent them to Black families but wouldn’t invest in upkeep. And due to a combination of banks denying them mortgages and a G.I. Bill that excluded Black veterans from low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans, most of those Black families were unable to buy those houses.

Even faced with these aggressive calls to sell, Sam Lesner kept his family firmly planted in Pill Hill.

Aryeh Bernstein grew up, became a rabbi and moved away from Chicago. After 15 years, he returned, pulled by the familiarity of the Southeast Side.

“Even just the names of the streets that only exist on the far East Side, from South Shore down Chapelle, Oglesby and Bennett, there’s a kind of emotional resonance to just the names of those streets,” he says. “Anytime I’m running an errand in South Shore in that area, there’s a certain kind of tingling … It’s a weird feeling of the accessibility of the old country.”

He and his wife Sarah had their daughter Avniel in August 2021. It was almost 135 years to the week since his forebears came over from Lithuania in 1888.