New research on old bones has shed light on pterosaur fossils from the early Cretaceous period of Australia, which took place roughly 107 million years ago.

The bones were discovered in Victoria in the late 1980s at a fossil site called Dinosaur Cove, a few hours’ drive west of Melbourne.

Our paper describing the bones is published today in Historical Biology.

The oldest pterosaur bones we have

The Dinosaur Cove fossils are the geologically oldest pterosaur remains we have from the Lower Cretaceous of Australia.

These bones belonged to two separate individuals, because there’s a relative size difference between the two.

One specimen is a partial sacrum (the fused vertebrae from between the pelvic bones), a relative rarity in the pterosaur fossil record. The other is a comparatively small fourth metacarpal (part of the wing finger) – it is the first evidence of a juvenile pterosaur found in Australia.

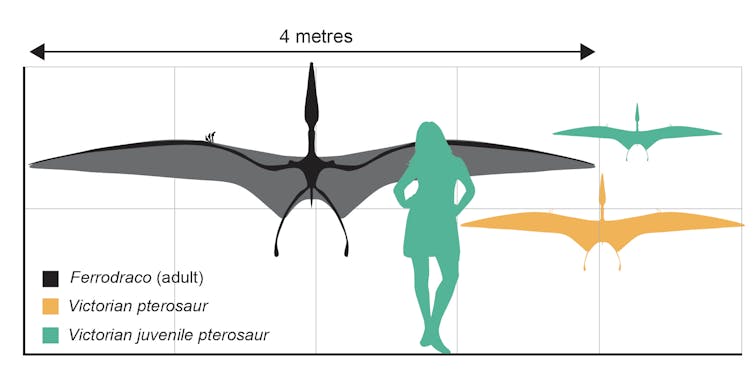

Although we couldn’t pinpoint exactly which species in the pterosaur family these bones came from, the partial sacrum belonged to an individual with a wingspan estimated to exceed two metres. By contrast, the juvenile pterosaur had a wingspan just over one metre.

In the early Cretaceous, approximately 110–107 million years ago, Victoria was virtually unrecognisable. The Bass Strait was a narrow valley occupied by fast-flowing rivers. Conifers and ginkgoes grew here instead of eucalypts and grasses, and dinosaurs reigned.

On the ground, the dominant herbivore animals were small-bodied, beaked ornithopods, perpetually wary of the rapacious megaraptoran theropods.

For more than 30 years, it has been clear to scientists that flying reptiles called pterosaurs soared through the Victorian Cretaceous skies, above the heads of the dinosaurs. Until recently, however, they have remained a mystery.

Treasure at Dinosaur Cove

Large-scale excavations at Dinosaur Cove began in 1984, and for more than 40 years, a team of volunteers called Dinosaur Dreaming have excavated fossil sites along several other sites scattered across the Victorian coast.

Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich, co-authors of our newly published paper, led the excavations that yielded not just the newly described pterosaurs, but myriad other discoveries as well.

The work at this rich fossil site has resulted in thousands of dinosaur bones and other fossils. These include fossil fish (bony fish and lungfish), skeletal remains from ornithopods, megaraptoran theropods, aquatic plesiosaurs and prehistoric mammals. There was also Australia’s only elaphrosaurine theropod: a lightly-built dinosaur with a small head, long neck, relatively short front limbs, long hind limbs and a long tail.

But among the rarest vertebrate fossils from Dinosaur Cove are those from pterosaurs.

Read more: Meet the diverse group of plant-eating dinosaurs that roamed Victoria 110 million years ago

Australia’s pterosaur record

The majority of Australia’s pterosaur fossils have been found in central-western Queensland. Indeed, the first pterosaurs reported from the continent were isolated remains from the Eromanga Basin, described in 1980.

Since then, more pterosaur material has come to light, with four Australian pterosaur species currently recognised: Mythunga camara, Aussiedraco molnari, Ferrodraco lentoni and Thapunngaka shawi.

Ferrodraco is the most complete Australian pterosaur to date, and is represented by an adult individual with a wingspan of approximately four metres, which we named as a new species in 2019.

Read more: 4-metre flying reptile unearthed in Queensland is our best pterosaur fossil yet

Other pterosaur fossils from Australia include isolated remains from the Cretaceous of Western Australia, and opalised pterosaur teeth from the mid-Cretaceous of Lightning Ridge in New South Wales.

We don’t know which species the Victorian pterosaurs belong to. However, the comparatively small fourth metacarpal – a bone from the wing – is the first unequivocal evidence of a juvenile pterosaur from Australia.

Pterosaurs at high latitudes

Few pterosaur remains have been reported from fossil sites that were at high latitudes during the Age of Reptiles – the Mesozoic Era.

Antarctica, which was at high latitudes throughout, has produced three pterosaur fossils. One of these awaits formal description, and another was recovered from the charred remains of the National Museum of Brazil.

The only reports of high-latitude pterosaurs in the northern hemisphere are of isolated footprints.

During the Cretaceous, Australia was farther south than it is today. In fact, Victoria was within the polar circle during much of the Cretaceous. Southeast Australia was not frozen over at this time, but there were weeks or months of continuous darkness during the winter. Despite these harsh polar conditions, life found a way to survive and thrive.

This prompts a few questions: were pterosaurs permanent residents in southeast Australia? Or did they migrate south during summer and head north for the winter?

From a young age, pterosaurs were adept fliers, their bones already able to withstand the stresses of both launch and flight. However, subtle variations in the shape of the bones imply that hatchlings differed from their adult counterparts in terms of speed and manoeuvrability.

Until we discover pterosaur eggs or embryonic individuals at sites that were at high latitudes at the time, we won’t be able to confirm if pterosaurs were year-round residents or migratory.

Despite the rarity of pterosaurs in the fossil record, it is only a matter of time before we find more complete pterosaur material from Dinosaur Cove and other Cretaceous sites from coastal Victoria. Then, we can finally uncover the identity of these ancient, enigmatic winged reptiles.

Adele Pentland receives funding from the Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend.

Stephen Poropat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.