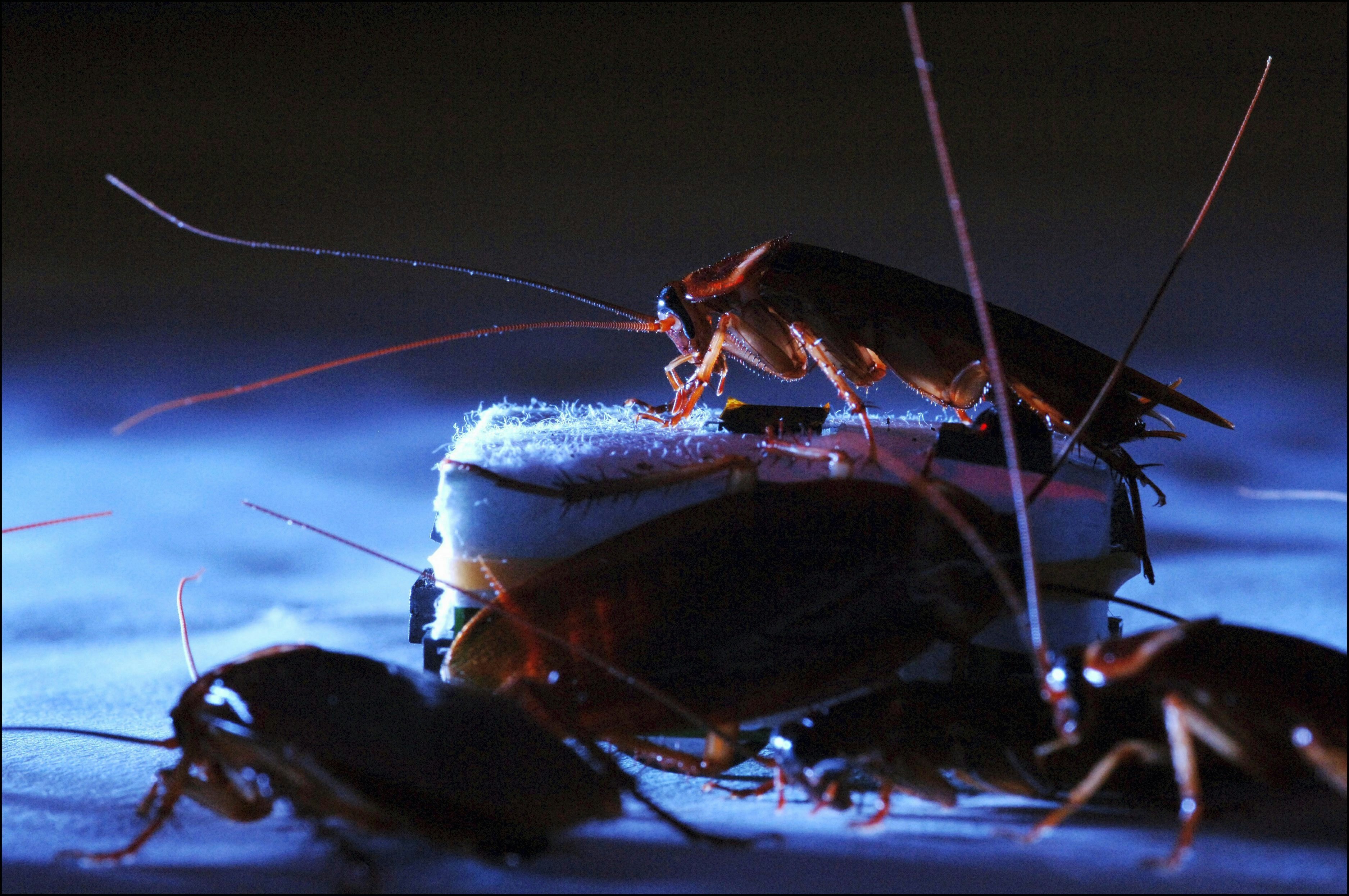

Cyborg bugs, enhanced with wires in their brains and electrodes fused to their exoskeletons, sound like something ripped from the pages of a pulpy sci-fi novel. But scientists have been trying to create these robotic insects for over 70 years, given their potential to spot victims during rescue missions — and even to spy on us.

Now, these tiny soldiers just became a lot more energy efficient. An international team of engineers has created a thin, flexible solar-powered device that turns cockroaches into cyborgs. Their work was recently published in the journal npj Flexible Electronics.

What’s new — The researchers hope these robo-bugs could revolutionize search-and-rescue efforts by reaching tight spaces that humans can’t and detecting people covered in rubble.

“Collapsed buildings, that’s a dangerous situation,” says Kenjiro Fukuda, an electrical engineer at Japan’s RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR) and senior study author. Sometimes, human-sized vehicles are simply too large to sift through the rubble, “[but] the insect is very small,” he says.

For this initial proof-of-concept, Madagascar hissing cockroaches made the perfect test subjects: These thumb-sized insects are broad enough to support a “backpack,” and they don’t have wings, which the researchers worried might shade their solar-powered device.

Why it matters — Fukuda hopes that his team can eventually create cyborg rescue rangers out of a wider range of creepy crawlers. “In the near future, maybe we can apply this to flying insects, such as beetles or butterflies,” he says, allowing them to probe even harder-to-reach disaster sites.

And in addition to search and rescue operations, defense experts say that these living drones may have enormous potential in the world of espionage, allowing intelligence agencies the ability to (literally) bug a room.

Here’s the background — Robo-bug hybrids have a few advantages over straight-up tiny robots. For one thing, they tend to cost less — insects are cheaper than mini gears and levers. Also, they theoretically require less complex engineering because they already come equipped with locomotion and sensory input.

Researchers have been tinkering with these helpful cyborg insects for longer than you might expect: The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) started researching insects’ spy potential in the 1940s, according to documents released by the agency in 2016.

And since 2006, DARPA has sought to fund cyborg bug projects. Now, the robot-insect arms’ race has intensified as other organizations, including RIKEN CPR, have joined in.

Cyborg insects are no easy feat. DARPA’s bugs have encountered some, well, bugs in the past. For one, the tiny creatures’ mobility tends to be limited by their clunky technological enhancements, which are often expensive and difficult to attach in the first place.

Then there’s the problem of battery life. Many early-concept cyborg insects can only run for a couple of hours before their control mechanisms need a recharge, which isn’t helpful during long missions.

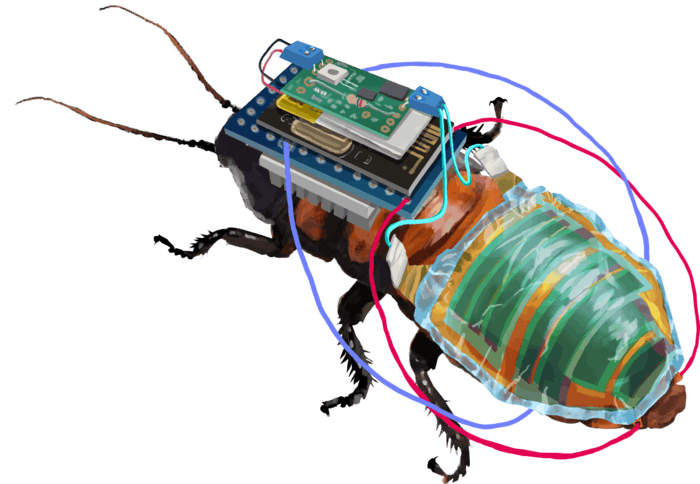

What they did — The new research overcomes these two hurdles. Unlike previous mechanically enhanced insects, Fukuda’s team crafted their control pad backpack out of an ultra-thin, flexible, and soft electronic film. These patches bend with the robo-roaches’ bodies, allowing them to move around freely and even right themselves if they flip over.

What’s more, these insects aren’t augmented by invasive means. Instead of jacking directly into the bug’s brains, the engineers devised an external control that sends electrical signals to the cerci, or the natural sensory structures at the rear of the abdomen.

By gently zapping these structures, the researchers are able to direct the roaches to turn left or right without all that messy brain surgery.

To solve the battery life issue, the engineers developed a similarly wafer-thin solar panel cell that adheres to the insect’s abdomen like a band-aid. That way, any time the bugs wandered into a sunbeam, they charged up their control hardware.

What’s next — The cyborg cockroaches have some distinct advantages over their enhanced cousins currently in development, but you aren’t likely to see them wandering around any disaster areas anytime soon. First, they’ll need a few upgrades.

For example, the current system lacks sensors, Fukuda says. In the future, the team wants to look into various sensors, like cameras, thermometers, or carbon monoxide detectors, and decide which ones would work best for different operations. They also want to further refine the solar cell component so that it can generate more power, even in indirect sunlight.

In the distant future, be on the lookout for roaches wearing mini backpacks. They might eavesdrop on your conversation — or even save your life.