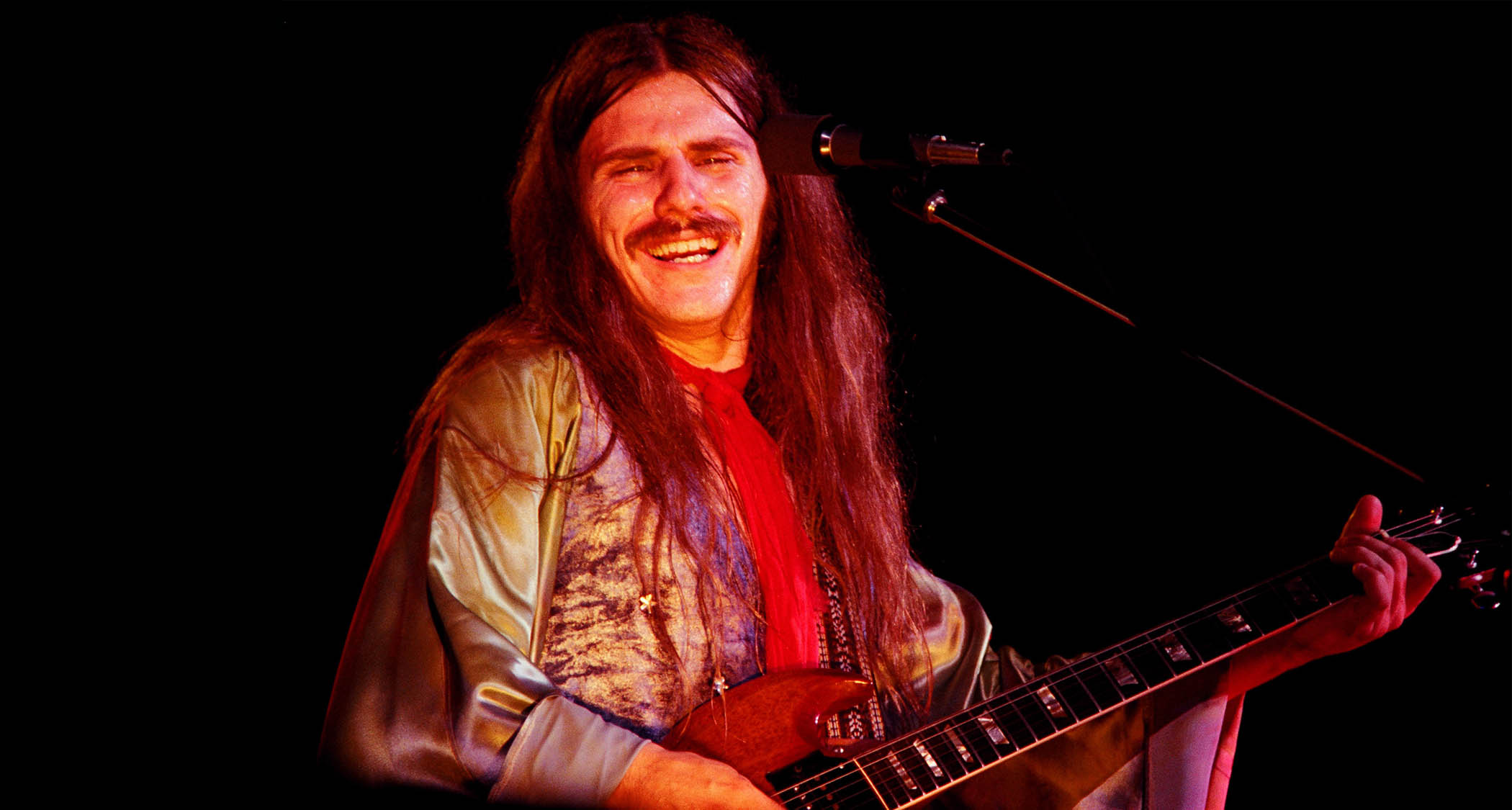

If you’ve heard the cavernous sounds emanating from the 20-second opener to Mahogany Rush’s 1978 Live record, Introduction, then you’ve probably caught the vibe of Frank Marino, a Canadian virtuoso whose influence is only rivaled by the shadows cast by his ever-colossal pedalboards.

Marino, who was born in Montreal in 1954, easily traversed the genres in the ’70s, laying down hard rock licks as effortlessly as he did blues and psych across records like Maxoom (1972) – recorded when he was just 16 – and Mahogany Rush IV (1976), which – despite being critically panned at the time – is seen as a masterstroke on the backside of songs like Dragonfly, which Marino says he “put together in about five minutes.” Damn.

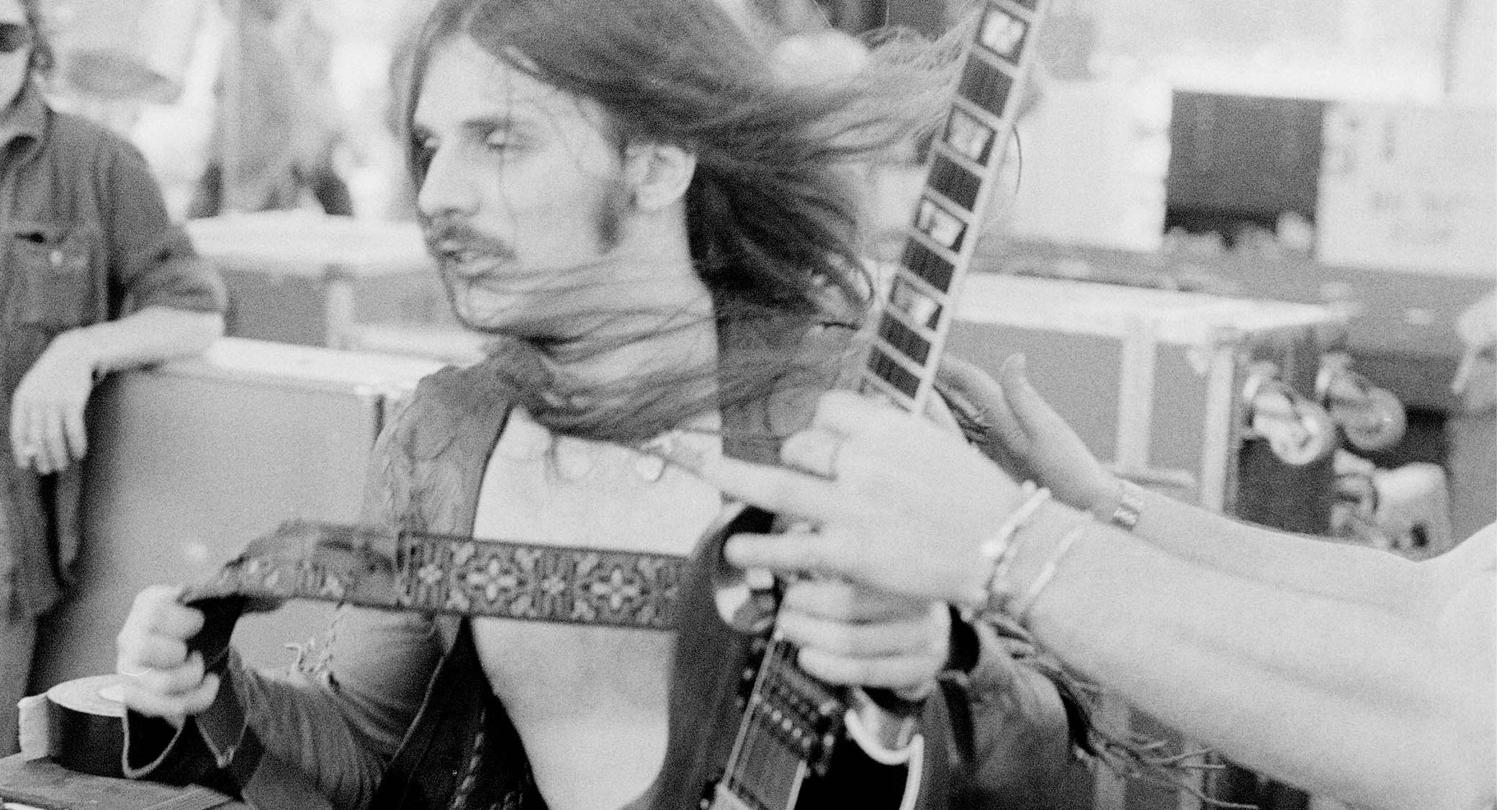

Given those accomplishments, it’s hard to believe that when he recorded those records, he’d only been playing guitar for a few years. What’s more, he only picked the hobby up out of boredom during a stay at Montreal Children’s Hospital after an acid trip gone wrong.

The latter is also interesting as Marino went on to be notoriously drug-free, but regardless, after being laid up in the hospital, the guitar stuck. “I had learned how to play on an acoustic because that’s all they had,” Marino tells Guitar World. “There was nothing to do except stay in my room and play acoustic guitar.”

Marino’s stay also triggered a rumor that dogged him throughout the 1970s. The story goes that as the then-14-year-old lay in bed recovering, he was visited by the spirit of Jimi Hendrix. While that’s nice, if not absurd, it didn’t happen.

No one bothered to ask Marino himself. Making matters worse, Marino’s style was reminiscent of Hendrix, or as Marino puts it, he “did that style too well,” which added fuel to the fire.

“There’s a funny story aside from that,” Marino says. “In ’68, I went to a Jimi Hendrix concert before I was a guitar player – and before I’d gone to the hospital. I left.

“I thought it was a bunch of noise. I left, and was the only person who left. Later, when Hendrix’s name followed me everywhere, it almost felt like Jimi Hendrix was saying, ‘I’ll make sure you never forget my name.’ It was hard.”

What wasn’t so hard for Marino was ripping it up on guitar and making awesome records. It came so easily for him that he broke into a biz as a kid – a biz he instinctively loathed. “It’s a little bit remarkable they allowed a 16-year-old to make and produce his own records,” Marino says. “And to be on a label. I had to learn as I went; it was like a big school. I lucked out.”

My entire life with record companies was one big argument. From beginning to end, they didn’t like my records

Luck had nothing to do with it, as Marino was talented, and his music with Mahogany Rush proved it. The problem was that Marino’s band was from out in the sticks, unlike Rush, April Wine and Bachman-Turner Overdrive.

“It wasn’t just that we were Canadian; we were from a province in Canada that didn’t get recognition – Quebec. There were bands from Toronto and out west, and there was a big scene, but we were never part of that scene. Those bands did well; we didn’t. We came from a place off the beaten path, and American record companies didn’t get the music I was doing.”

Marino has a point; unlike Rush, who also made deeply complex music, his music wasn’t based on interesting vocals. And unlike Bachman-Turner Overdrive and April Wine, Mahogany Rush had no true pop element.

“My entire life with record companies was one big argument,” he says. “From beginning to end, they didn’t like my records. I often wondered why they kept me on the label. Every time I did a record, it would come out, and they’d say, ‘Well, let’s do another,’ but there was never any promotion, and we couldn’t get anything on the radio.”

Radio be damned, though, as grassroots touring alongside Aerosmith and Ted Nugent granted Mahogany Rush a following. And soon, Marino’s legend as a hyper-gifted proto shredder with otherworldly, full-on mad-scientist-sized pedalboards and giant stacks of solid state amps began to grow.

“The way we became as ‘big’ as we did was by playing a lot of shows as an opening act,” he says. “It was word of mouth that helped more than anything. And then we did the Live record.

“The record company tried everything not to have it come out. But that ended up being our best-selling record. I could never figure out why they were so against that record.”

By the end of the ’70s, my outlook hadn’t changed. Concerts had become bigger and bigger; it was the same atmosphere you saw at Woodstock

By the end of the ’70s, Marino was just 25, shockingly young for a man who had survived an over-the-top acid trip, supposedly met the ghost of Hendrix – and been haunted by him – and dropped six studio records and one live album. Though he might have been young, He was wise beyond his years.

“By the end of the ’70s, my outlook hadn’t changed,” he says. “Concerts had become bigger and bigger; it was the same atmosphere you saw at Woodstock. It wasn’t the same; people didn’t look at it the same.

“I remember once, I was standing with [Mahogany Rush drummer] David [Goode]; he looked out at the crowd all going crazy, and since the ticket prices were pretty low, he said to me, “You know what this is, Frank? This is basically cheap psychiatry.’”

At the top of the decade, there were rumors about you spending time in an institution and being visited by the spirit of Jimi Hendrix, which seems ridiculous now.

“Those rumors were extremely bizarre and were created by one guy who wrote an article for a local paper, which was used as fodder for all the articles that came out in guitar magazines. It was stupid and pretty bizarre.”

You were very young then, only 16. Was that difficult to handle?

“And I was nobody at the time. Nobody bothered to find me, especially in Canada, to find out how accurate the rumors were. They were these preposterous rumors that had to do with me going to the hospital – and I did go to a hospital – and being visited by the spirit of Jimi Hendrix.

“And it was ridiculous because I went to the hospital in 1968, Hendrix died in 1970, and they said this happened after, so it was a totally preposterous rumor.”

So what’s the truth of the whole matter?

“I went to the hospital, learned how to play guitar in hospital and came out and played the music of the day: Hendrix, the Beatles, the Doors and other stuff from the late ’60s. Maybe I did the Hendrix part a little too well because this writer wrote this ridiculous piece, and that was the bizarre beginning that followed me.”

What was the blueprint for Mahogany Rush’s first record, 1972’s Maxoom, which was recorded two years before, when you were 16?

“My intention was to simply play rock guitar music in a band. It was as simple as that. You didn’t have a lot of 16-year-olds doing that, you know? I was 13 when I went into the hospital and 14 when I started to play guitar. By 16, I’d made an album, which didn’t come out until two years later.”

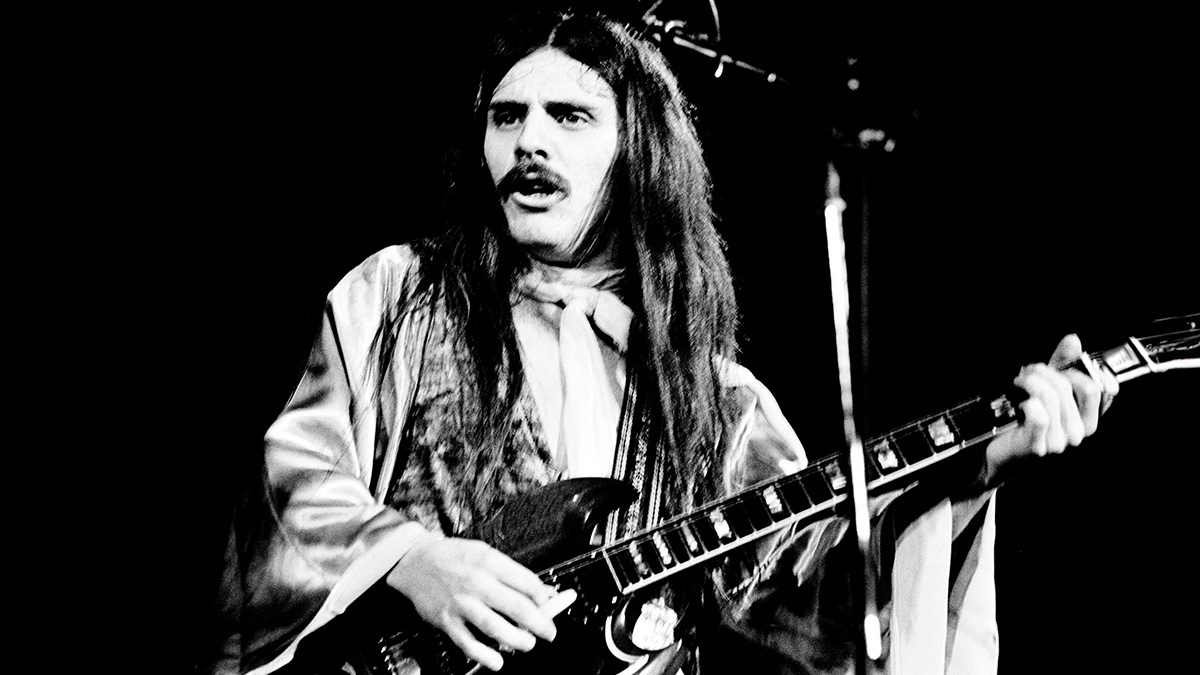

Once you became established, you started to get known for your trusty Gibson SG. What attracted you to that particular guitar?

“Quite simply, it was when I came out of the hospital, and my mother went down the street to a neighbor selling a used guitar, which happened to be a 1961 Gibson SG. She bought it for 70 bucks, brought it home, and said, ‘Here, this will help you.’

“That became my guitar, and I just kept on playing SGs. When one broke, I went and got another. They were easy to play, I could reach all the notes, they had a fast neck, and they weren’t heavy like Les Pauls were.”

I came across DiMarzios a bit later, and I remember saying to them, ‘I want a standard pickup that sounds normal. I don’t want it extra strong or anything fancy’

Another essential part of your unique sound was DiMarzio pickups. The guys in Kiss, for example, get a lot of credit for popularizing those pickups, but you also had a big hand in that.

“I didn’t use them in the beginning; I used whatever pickup was in the guitar, which were PAFs, so that’s the sound I had. I came across DiMarzios a bit later, and I remember saying to them, ‘I want a standard pickup that sounds normal. I don’t want it extra strong or anything fancy.’ They said, ‘Okay’ and gave me pickups. I stuck them in the guitar and used them from then on.”

Considering you recorded Maxoom as a 16-year-old kid, your learning curve must have been pretty steep as you trucked into the ’70s and beyond.

“Well, I was technically included and learning about electronics. At the same time, I was learning how to do things in the studio without equipment because the equipment that was available, I mean… the first album was done in eight-track, and the console didn’t even have EQ.

“If I wanted to EQ something, I’d have to run out of the room, move the mic, and get a little more treble or bass on the guitar. I started learning how to get around the limitations of the gear and got better as the albums went on. I became more well-versed in terms of shaping sound and was fortunate.”

Mahogany Rush’s first three records were on indie labels, Kot’ai Records and Nine Records, but you eventually were signed to Columbia Records for 1976’s Mahogany Rush IV. Considering you were anti-establishment, was that a struggle?

“I didn’t want to be signed. I wanted to be one of those anti-establishment guys. I was like, ‘Oh, no, I don’t want to be commercial.’ And the way that they signed me was by saying, ‘Okay, you can go and produce your own stuff, and we’ll never get involved.’ That’s what the early labels said, and Columbia actually bought my contract with that provision, which was totally unheard of then.”

You mentioned your technical inclination, which extended beyond the studio and led to your creating some of the earliest pedalboards well before they became commonplace. What drove you to do that?

“It was simple. It was like, 'You have this choice: plug your guitar in or stick it into an amp and hope it sounds good. Or you can create some kind of interface that will end up sounding like a lot of different things.'

“I didn’t want just a clean and dirty sound; I wanted octaves and flanges. I wanted different sounds, and building them as pedalboards and amplifying those gadgets on my board helped me do that.”

Despite having full control of your records and innovating gear across the board, Mahogany Rush struggled to chart. That must have been frustrating.

“You had to have radio. If radio decided they liked you, if programmers at radio liked your songs, then the record company loved you. I always thought it was the record companies’ job to go and get you radio play, but they didn’t do that.

“They just waited for the programmers to tell radio what the newest stuff would be, and they would credit or discredit the band based on whether it was on the radio. That was the problem. We weren’t a band that got on the radio often; the only time I was, it was a cover song.”

One song that wasn’t a cover and has gone on to be revered by your fans is Dragonfly from Mahogany Rush IV. Do you remember putting that one together?

“I do. I put that together in about five minutes. One of the things about my albums is every session we ever did for every album when we walked into the studio, we had no songs. We would walk in with nothing. I would tell the guys, ‘Give me a few minutes to write a song,’ and I’d write a song.

“Then, they’d walk in, learn the song, record it, and that would be the song. Every album was like that; there was no pre-production. Dragonfly was another one of those tunes.”

Every session we ever did for every album when we walked into the studio, we had no songs. We would walk in with nothing

Another critical piece for rising bands in the ’70s was getting a good opening show with a big headliner, which you did with Aerosmith and Ted Nugent.

“We had the same manager. The reason we toured so much with Aerosmith and Nugent was because David Krebs was their manager, and mine. Personally, I thought the type of music we did… I adapted to that kind of music when I did those shows. I can do any music; I can play rock, fast guitar, and psychedelic. It’s all the same to me.”

So, looking back – and I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with their music because there’s not – but do you think Mahogany Rush belonged on tour with those types of bands?

“Well, I wasn’t going to go on stage, you know, to 200,000 people and play some of the more eclectic, slow ballads that I would do on some of our early albums. What I would do is do more bluesy rock-oriented tunes because they fit. It was still me – I wasn’t mailing it in, but that was just one side of me.

“I always thought we might have been better served – and David [Krebs] even thought this after it was all over – if we’d played with certain types of different groups and audiences. Our music was never really coming through; we weren’t really doing a lot of stuff from the studio albums; we were doing more stuff from the live album.”

That album, 1978’s Live, is considered one of the best live recordings of the ’70s. Back then, bands were big on overdubbing their “live” records; was that the case for Live?

“They really were live performances. There was no… I mean, I didn’t do any kind of going back to the studio with the live record to redo the guitars or bass or stuff like that. But sometimes, you would enhance the crowd sound because they weren’t mic’d the same way. You know… you might do something like that.

“This was 1977 and 1978, and it was pulled from 12 different shows, edited together and mixed into one album. There was some production that went on there, but it was more a question of how to make 12 different shows sound like you were at one show. And how you’d do that is enhance how the crowd sounded so it sounded natural.”

Another important live moment for Mahogany Rush was California Jam ’78. Can you describe what that was like?

“It was a long day. We were slated to go on after the headliner, which was Aerosmith. I guess the promoters thought they would, you know, they thought we were supposed to provide music for the exit, but it didn’t turn out that way. It turned out that when we came on after Aerosmith, it almost felt like we were the headliner. [Laughs]

“I wasn’t and certainly wasn’t in terms of pay, that’s for sure. [Laughs] But I remember a sea of people and how big it was. It was astronomically big; I think there were over 300,000 people there.

“You couldn’t see all of them at night, but I went on stage during the day when some of the other bands were on and looked out at it. It was pretty big, and it was quite the thing to do.”

By the time Mahogany Rush recorded 1979’s Tales of the Unexpected, how had your outlook regarding the music industry shifted compared to the top of the decade?

“My view of the music industry was the same all the way through. I really didn’t like it, and I didn’t like the way they did things. It’s almost like my first impression of when they first came to sign me, and how I didn’t want to do that, turned out to be right. It wasn’t what I expected it to be.”

My view of the music industry was the same all the way through. I really didn’t like it, and I didn’t like the way they did things

How so?

“I grew up in the Woodstock generation. I thought getting there would be like that. But by the time I got there, things had changed. When I was young, you didn’t go to a ‘show’; you went to a concert. People would ask, ‘Are you going to the pop concert?’ But by the time I got there in the ’70s, half of the people were calling them ‘shows,’ and it had become a spectacle.”

Still, you accomplished a lot. From your sound to your gear to your technique, your ’70s albums have influenced droves of guitarists. Industry issues aside, that must be gratifying.

“I’m always honored when people say I’ve influenced them in one way or another. I mean, that, to me, is… what did I really want to get out of anything? All I wanted was respect because I knew I wasn’t going to get any money. And I wasn’t a drug user or a drinker, so I wasn’t getting the party atmosphere, you know?

“I feel really good about the fact that people say they were influenced either by the gear, the music or my playing. That’s why I build pedals [Frank Marino Audio] now.

“I want to give the people some of the same experiences I had with the sounds I actually used. It’s something I can give back to people, which gave me quite a bit.”

Learn more about Marino's stompbox range at Frank Marino Audio.