Our VR future apparently involves virtual wine tasting, virtual museum visits, and a whole lot of virtual meetings.

Maybe this sounds familiar. Maybe that’s the point.

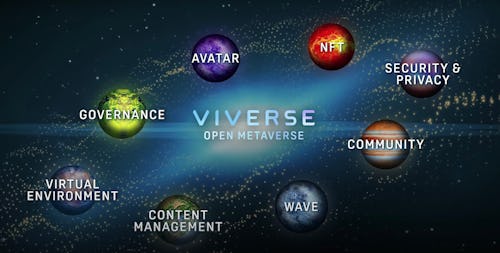

HTC revealed its interpretation of “the metaverse” or should I say “Viverse,” at MWC 2022 last week. A somewhat unspecific vision, full of references to other concepts in the zeitgeist. The company calls out AI, 5G, and NFTs in its various announcements — an unfortunate and, I imagine, an unintentional callback to Foxconn’s “AI 8K+5G ecosystem” it initially claimed it was building in Wisconsin.

What’s striking about HTC’s Viverse pitch and its surface-level connections to all the buzziest of tech buzzwords of the last five years, is how it helps to further illuminate Meta’s story — the other company with a public “metaverse” vision. There’s something wrong in the push towards building the next big platform in tech, and it has everything to do with what these companies have and haven’t told us.

The promise

What exactly are these companies promising? The vagueness is partially deliberate here, I think because the product these pitches describe doesn’t exist. HTC provides this as its basic description of the Viverse:

“Viverse, is our version of the metaverse; an immersive, boundless universe of fantastic new experiences, and a seamless gateway to other universes in collaboration with our partners from the time you wake up in the morning until the time you go to sleep at night.”

Here’s Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg from the “Founder’s Letter” he wrote, timed with the company’s rebrand to Meta:

“The next platform will be even more immersive — an embodied internet where you’re in the experience, not just looking at it. We call this the metaverse, and it will touch every product we build.”

And:

“The metaverse will not be created by one company. It will be built by creators and developers making new experiences and digital items that are interoperable and unlock a massively larger creative economy than the one constrained by today’s platforms and their policies.”

So there’s a vision of a boundless digital VR/AR space, with new and exciting experiences, economic opportunities (sigh), that will only be possible with the help of “partners” or maybe, “everyone.” I’d like to key in on Meta’s use of the phrase “embodied internet” and expand it to the web at large because it seems like Meta is referring to more than just infrastructure, and I think that might be the easiest way to understand what the hell both these companies are talking about. If the metaverse or Viverse is the VR version of the web, what would that mean?

A new web

I’ll borrow my favorite easy definition of the open web from ex-The Verge’s Dieter Bohn. For an app or website to be part of the open web it has to be two things:

- Be linkable, as in, have some way for anyone to point to them

- Allow any client to access it, as in, let any browser, app, or device participate, regardless of who or what made them

There are a lot of philosophical conclusions you could draw from those two requirements. Free speech is valued on the web, as is anonymity, some concept of decentralized ownership (starting with hosting and coding your own website), and open infrastructure that could allow anyone to participate and innovate on what’s already there. All good things on paper, with their own complications to be ironed out (see: the never-ending debate over free speech online, harassment, etc.)

Are any of those ideas reflected in how VR works today? Is there anything even approaching the openness of the early internet and web in the current VR ecosystem?

“It just seems like using the same tools and encouraging others to do the same.”

To both Meta and HTC’s credit, they are members of the organization developing OpenXR, an open API that’s designed to eliminate fragmentation across VR and AR platforms. HTC is also supporting WebXR in its Vive Browser and Vive Connect app, the open standard for developing VR experiences for the web.

But supporting these open standards isn’t exactly the same thing as directly collaborating on a shared, ideally global project like “the metaverse.” It just seems like using the same tools and encouraging others to do the same.

A new App Store

My experience using a headset like the Quest 2 or HTC’s Vive Focus 3 is one that’s more like using a smartphone than it is a laptop or desktop computer. That shouldn’t be entirely surprising. Besides using similar components to modern smartphones, both headsets use operating systems that are based in part on Android (including Vive Wave, HTC’s “VR open platform”).

Using mobile devices as inspiration isn’t a bad thing. Smartphones and tablets are easier to use than traditional PCs, but that doesn’t change the fact that the experience of VR today is interacting with app stores and apps, not the wild and fluid space that is the internet and the websites that run on it. Both companies’ early vision for metaverse experiences, like Vive Connect or Meta’s combination of Horizon Home and Horizon Worlds, have similar limitations. They’re more siloed off than anything I imagine when I think of “the metaverse.”

We’re obviously early on in whatever this larger metaverse trend will be, so there’s no need to count chickens before they hatch. But there’s also no reason to believe there are any eggs here at all. Looking at HTC and Meta’s different, but on some level equally desperate attempts to make “the metaverse” a thing, I don’t see companies excited to work together on a popular new platform, I see companies hoping to own the next big platform.

The dominance of the app store model, and particularly Apple’s very lucrative flavor of it, has to be hugely attractive (and feel very unfair) to a company with money to burn on making a new technology dominant. That’s what Epic, Apple, and Google’s big fight over Fortnite is about on some level.

“It’s iOS with a little more wiggle room.”

Meta was at the bad end of the app store money funnel since its conception, and as the possible owner, or at least loudest contributor to the next major turn in computing, it could bake in its own form of dominance at an even higher level. HTC obviously sees the potential there too, and an opportunity to make its phone business once again as relevant as its VR one. Hence the rumors of a “metaverse phone.”

But an expansive, exciting platform owned or quietly controlled by a big company is not the same thing as the open web, or what I’d want from an “embodied internet.” It’s iOS with a little more wiggle room.

Do it different

Instead of speaking optimistically about what’s possible in “the metaverse” (something that again, doesn’t exist and might never) or flailing wildly to connect all of the current hot topics in the tech world, companies like Meta and HTC should be talking about how they’re going to work together to build something new. The metaverse should lie at the end of a long and boring process of iteration and open standards, not unrealistic pitch decks and presentations.

People are doing wild things and making exciting connections in VR — there’s promise in an even more approachable and interconnected version of what we have today. Zuckerberg has said he thinks the metaverse is less a replacement for the internet than it is a successor (a more immersive one) to the mobile web Meta made its billions on. But he's said many aspirational things and walked them back when the rubber met the road.

For all their talent in making VR hardware, I’m deeply skeptical that Meta and HTC will be the companies to do it, or that companies should be the ones defining whatever the next internet is in the first place. In retrospect, it’s a realization that should have come earlier, but one I’m glad to have made.