A sharp rise in the number of hospital beds occupied due to patients suffering with norovirus has been reported by the NHS this year. According to the latest NHS weekly report on hospital bed occupancy, around 351 people on average were admitted to hospital every day last week with symptoms of diarrhoea and vomiting. During the same period last year, only 126 people were admitted with these symptoms.

But while the NHS is attributing these hospitalisations to norovirus, the numbers don’t suggest the UK is currently facing an outbreak. In fact, the latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) for the same period shows that cases of norovirus aren’t any higher than in previous years.

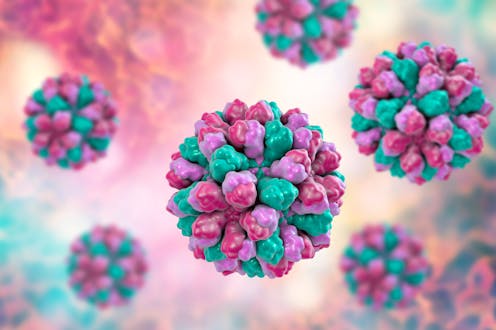

The common name for norovirus is the “winter vomiting bug” – and as this suggests, the main symptoms of an infection are vomiting along with diarrhoea and persistent nausea. These symptoms can be accompanied by a high temperature and aches, but this is not as common.

Norovirus symptoms typically last a couple of days and treatment isn’t usually needed. Most patients can manage their symptoms by keeping hydrated and resting. But, in severe cases (especially in children and older adults), dehydration can become an issue and hospitalisation is needed.

But while there’s been an increase in people hospitalised due to diarrhoea and vomiting in recent weeks, that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re facing a norovirus outbreak.

According to the latest report published by the UKHSA, there’s no unusual increase in norovirus cases compared to the previous five years. While their report states that case numbers are up from weeks previous, they’re no higher than compared to previous years.

In fact, the report shows that norovirus cases are 20% lower compared to the previous five-year average for the same two-week period. Hospitalisations for norovirus are also lower this year than they were compared to the same time last year, according to UKHSA data.

Other possible causes of hospitalisations

So what might explain the discrepancy between the NHS’s hospitalisation data and the UKHSA’s data on norovirus cases?

Previous data has shown that UK norovirus trends are much more variable than in previous, pre-pandemic, years. More outbreaks are being observed in schools, nurseries and care homes. Unusual peaks are also being seen at unexpected times of the year.

So we could be seeing another unusual peak in norovirus cases, driven by a variety of factors – including some people’s immune systems not being primed to stave off the virus effectively, or changes in protective habits such as less hand washing.

The recent spike in hospitalisations could also indicate that the norovirus strain currently circulating is causing more severe symptoms.

It’s important to note as well that the NHS seems to be attributing to norovirus the surge in hospitalisations due to symptoms of vomiting and diarrhoea. While vomiting and diarrhoea certainly are symptoms of norovirus, they aren’t the only reasons a person may experience these symptoms.

Many other viruses and bacteria can cause gastroenteritis (inflammation of the stomach and intestine) such as rotavirus and Campylobacter.

Rotavirus is very contagious and typically causes diarrhoea. Rotavirus case numbers are also reported in the same UKHSA document. While overall rotavirus numbers are up this year, the most recent weeks have seen these numbers decline again.

Campylobacter is a group of bacteria that can cause stomach infections, usually due to touching uncooked poultry. While we can see cases all year around, we tend to see more infections in late spring and early summer.

Despite the misleading name of stomach flu, influenza doesn’t cause diarrhoea and vomiting. In rare cases, COVID-19 can sometimes cause vomiting – but to have such a change in main symptoms in such a small period would be extraordinary and unlikely.

This complex web of causes, symptoms and hospitalisations makes finding a single cause difficult without more case number data, which will start to come out as the winter season progresses.

No matter the cause of these increased hospitalisations, the root issue is that there’s a much larger burden on the NHS due to admissions with diarrhoea and vomiting. Most pathogens that cause these symptoms are transmitted through touching an infected person, touching surfaces that have the pathogen and then touching your mouth – or eating contaminated food.

We all need to ensure we’re washing our hands regularly when handling food or being around susceptible people, such as children. Extra care is needed in schools, where increases in cases have been seen in previous years.

Of note, alcohol hand gels don’t stop norovirus infections. Only hand washing with soap and hot water can, as this destroys the virus and prevents it from being spread. This practice will also help fight against most other viruses and bacteria.

Conor Meehan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.