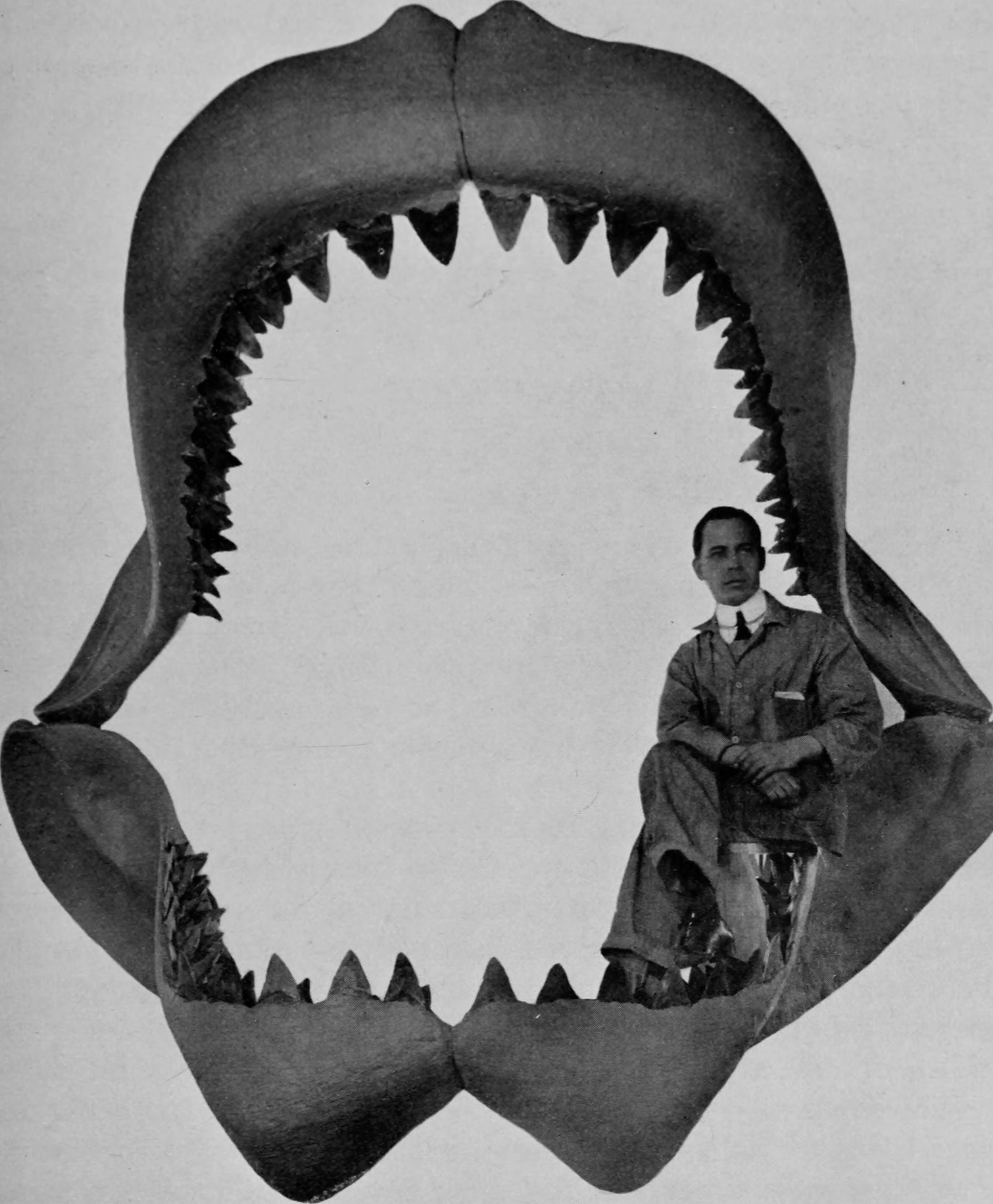

The most terrifying part of the Long Island Aquarium in New York is a replica megalodon jaw that hangs on the wall, disembodied but still seemingly poised for a bite. The display used to inspire a deep feeling in me whenever I saw it — it was big, I was small.

The megalodon inspires fear even 3.6 million years after it existed, and now new research provides an answer to why megalodons were so gigantic. You can find that story and so much more in today’s Inverse Daily.

This is an adapted version of the Inverse Daily newsletter for Tuesday, March 15, 2022. Subscribe for free and learn something new every day.

This overlooked factor could explain why megalodons got so massive

Carcharocles megalodon was up to 50 feet long. Carcharocles megalodon “left behind teeth as big as a human hand that can still be dug up from rivers and oceans today,” writes Inverse card story editor Jennifer Walter. “Size was a defining element of the species. But a new study reveals that there may be an overlooked factor that influenced how large megalodons could get.”

An analysis recently published in Historical Biology suggests that water temperature was responsible for megalodon being so, well, mega. “After adjusting for time and ocean temperature, they observed that larger megalodons seemed to be concentrated at higher latitudes, while smaller ones clustered near the equator,” writes Walter.

Possibly, more mass allowed the sharks to withstand freezing water, and less mass kept them comfortable in warm. Though this connection between temperature and size does not seem to be true for smaller-but-still-terrifying modern sharks, the phenomenon, which is called Bergmann’s Rule, can be observed in fish and elsewhere in nature.

Jaws in real life: Female whale sharks are the biggest fish in the sea

What did Einstein eat?

Famed physicist Albert Einstein had a significantly tinier jaw than megalodon, but he was still happy to chomp on delicious meals — when he remembered to eat, that is. Einstein once wrote to his second son, Hans Albert Einstein, that he was often “so engrossed in my work that I forget to eat lunch.”

Ditto for dinner. Reports suggest that “Einstein was more prone to getting wrapped up in conversation paying little attention to what he was eating,” writes Inverse health reporter Katie MacBride. But when Einstein did eat, he ate well. According to Einstein’s live-in housekeeper, Herta Waldow, Einstein enjoyed at least two fried eggs and mushrooms three times a day. Other accounts note a love of bread and butter, beans straight from a can, fruit, tea, and cheese.

Many of those foods are nutritionally dense, but “it’s impossible to tell if Einstein’s diet contributed to his tremendous brainpower,” writes MacBride. And regardless of what he ate, “the famed physicist was, unfortunately, plagued by chronic gastrointestinal issues throughout his life.” Eventually, a doctor recommended Einstein completely remove meat, fat, and alcohol from his diet. “His vegetarianism lasted only one year,” writes MacBride.

Brain food: Two vitamins found in meat may help treat an incurable brain disease

Should you wash pre-washed vegetables?

To wash or not to wash is so often the food question. Pre-washed fruits and vegetables seem to solve the problem before it’s even presented to you — things rarely require a post-wash, right? — but Inverse science reporter Elana Spivack is here to tell you the truth…

… Yeah, you don’t need to wash anything labeled as “pre-washed.” “While there’s never a 100 percent chance of annihilating every microbe on leafy greens, pre-washing actually seems to be pretty safe,” writes Spivack. In fact, “if someone washes their vegetables again at home, there’s a possibility of re-contamination from microbes in a dirty sink or on a counter where raw chicken had just been prepared.”

But not all pre-washing is created equal. “Some greens may be hiding more bacteria than others because of their dynamic, uneven surfaces,” writes Spivack, and according to a 2015 study from the University of California, Riverside, even washing spinach with bleach and water didn’t kill all E. coli microbes. But if food is so contaminated that an industrial pre-wash is insufficient, experts say the responsibility lies with the food industry and not you, the sink-ready consumer.

Just to be safe: Should you wash rice?

You need to see the last Full Moon of winter this month

After your nice, triple-washed salad dinner, head outside on March 18 to watch the Worm Moon, which is also nicknamed the Crow Moon, the Crust Moon, and the Sap or Sugar Moon in the United States. All these names come from the U.S. tradition of “naming its Full Moons after the monikers from various Native American Tribes,” writes Elizabeth Howell.

“These names became more widely known to non-Native Americans in the 1930s, when the Old Farmer’s Almanac began publishing weather forecasts and astronomical discussions for newer American settlers,” she writes. NASA says that the name “Worm Moon” is borrowed from the southern U.S. states, which might have been connecting March’s defrosted spring with increased worm activity.

But a Moon by any other name, etc. No matter what you call this full March moon, you can get a glowing glimpse of it at 3:17 a.m. Eastern on Friday. Don’t worry if that’s an undesirable time — “Full Moons stay above the local horizon all night, and with March’s still short days you’ll have many hours to enjoy the view,” writes Howell. If you still miss it, there’s always next March. Until then, you have April’s Pink Moon to look forward to.

Goodnight, Moon: NASA teases how Artemis astronauts will explore the Moon’s south pole

About this newsletter: Do you think it can be improved? Have a story idea? Want to share a story about the time you met an astronaut? Send those thoughts and more to newsletter@inverse.com.

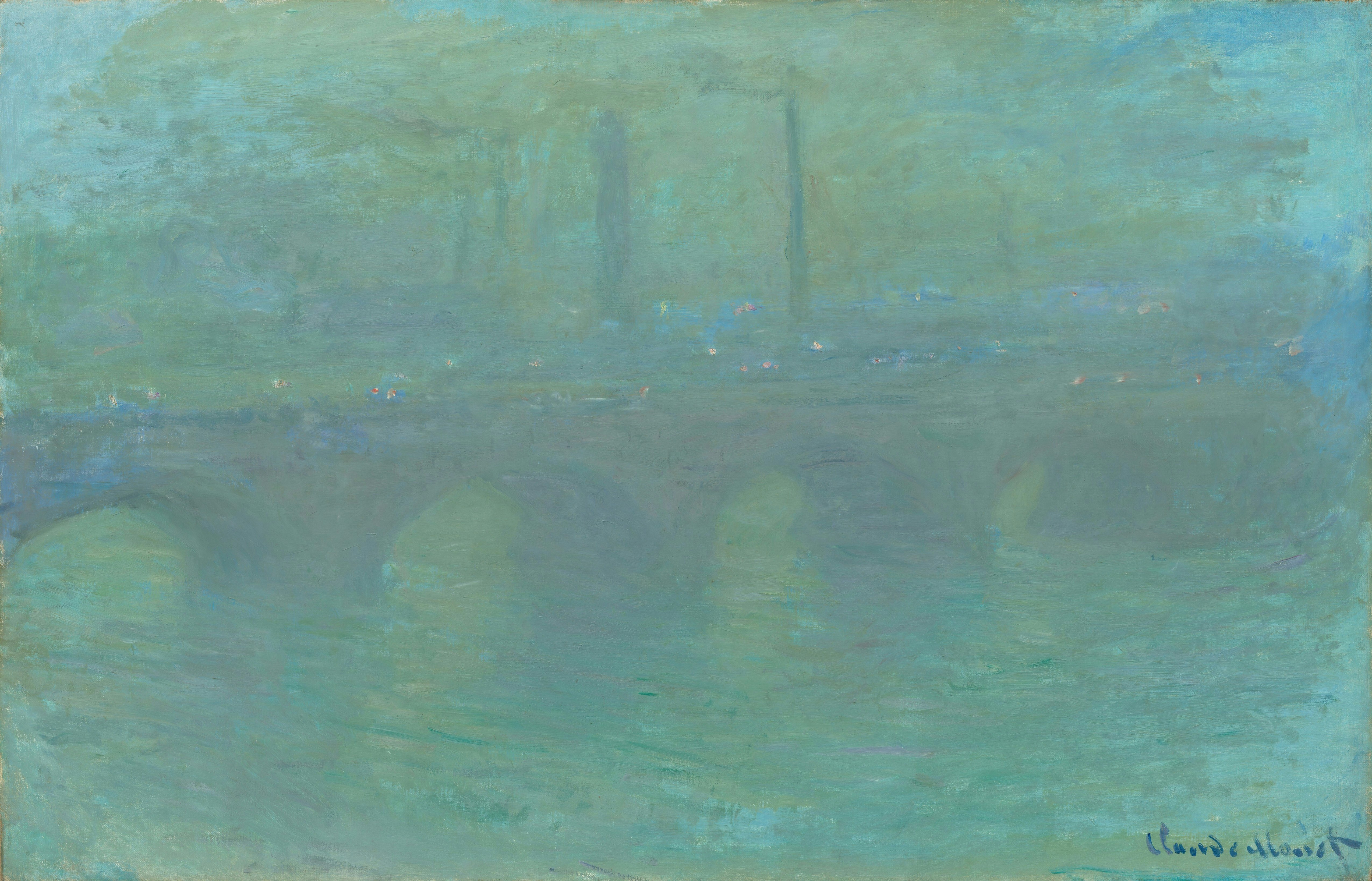

- On this day in history: John Snow, the English epidemiologist who helped save London from cholera, was born March 15, 1813. Later in his life, Snow worked to prove that cholera was transmitted by contaminated water, not miasma, which was generally believed to be the cause of disease. Eventually, Snow discovered a cesspool in a popular water pump and proved his point (gross!).

- Song of the day: “Still Clean,” by Soccer Mommy.