Annamma (Anna) Spudich still remembers the Pala tree she would walk past on her way to school as a six-year-old. She would be accompanied by her cousin, then in her teens, remembers Dr. Spudich, who holds a Ph.D. in Cell and Molecular Biology at Stanford University and was a research scientist at Stanford for 25 years. “The tree would produce white flowers at a certain time of the year,” she says, recalling how it fell twirling to the ground, because of the way the petals were positioned.

When she passed the tree in full bloom, however, her cousin would tell her to run, she says. “We were told that when the tree bloomed, you should not walk under it because there was a yakshi in residence,” says Dr. Spudich, who left her career in basic science in 2000 to explore the medical-botanical traditions of Southwest India.

Later, she discovered that the pollen of the Pala flower contains a potent nasal irritant that many people are highly allergic to. “Legends and stories, some of which are considered by modern science to be unrelated and absurd, codify medicinal plants and healing,” says Dr. Spudich, pointing out that storytelling was often an important tool to preserve and disseminate traditional folk medical knowledge.

Dr. Spudich, a visiting scholar at National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bengaluru since 2008, who delivered a lecture titled European Records of Botanical Medical Knowledge of Southern India at the Archives at NCBS, last month, speaks about her journey.

Could you talk a little about your introduction to folk healing as a child growing up in Kottayam, Kerala? How did your training as a molecular biologist shape the way you approached this tradition?

My interest in medicinal plants, their properties, and how they contain important bioactive molecules came partly from my scientific training and partly from the experience of growing up in Kerala. When I was growing up in the 50s and 60s, traditional medicine was very much a part of everyday life. You didn’t think about consulting a biomedical physician for my neck ailments, and antibiotics weren’t so common back then.

When you had a small cold or congestion, you would try something that was part of everyday life, like pepper water or cumin water. Or, if you had an intestinal upset, your grandmother would make some food that would take care of it. So, I was very aware of the idea of traditional medicine being a very important component of healthcare. And beyond that, the folk medical healers or vaidyas were consulted. Extracts, decoctions, poultices and so on, that were made from regional medicine or plants, were more commonly used than biomedicines.

During my career as an experimental scientist, I worked on the cytoskeleton of the cell, an important component that controls many functions of every type of cell in the body. Interestingly, it turns out that some of the small molecules that interrupt and influence the assembly of the cytoskeletal proteins in a cell are derived from plants and natural products. A cursory search also showed that some of the most successful and commonly used biomedical drugs are derived from natural products. For example, aspirin, and the malaria drug, quinine, were discovered for brand medical uses by traditional societies.

As I got more and more into basic sciences, I started to be intrigued by the idea that there is a great deal of information to be gained from traditional medical sources, that we as experimental scientists, were not taking advantage of. The extensive knowledge of single medicinal plants could build many successful therapies for intractable diseases. For instance, I was intrigued to discover the story of the drug reserpine from the Indian bazaar medicine Sarpagandhi and the enormous impact it had on understanding complex neural pathways.

You made a switch from experimental science to folk healing, a fairly drastic shift. Can you talk about what caused this move?

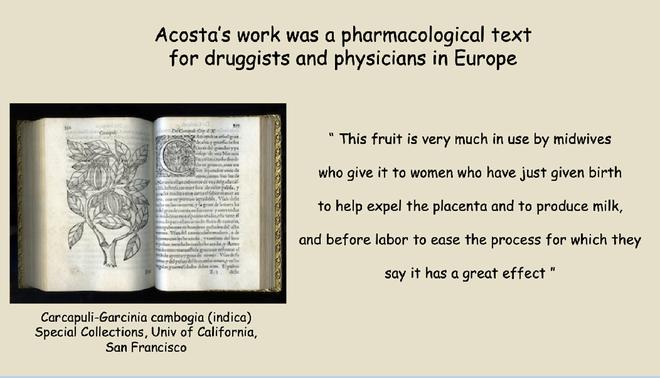

Many years ago, when my husband was a post-doctoral fellow at Cambridge, I started spending my spare time in the Cambridge library. There I came across a volume called The Greate Herball written by the British herbalist, John Gerard, published at the end of the 16th century, a 3-inch-high tome. It was intriguing for me to open the book and see images of Indian medicinal plants in the book. He had never been to India himself but had described around 200 or so Indian medicinal plants in the book.

I became aware of the fact that Indian medicines were available and used in Europe, as early as the 16th century. Also, I have always been interested in the history of East-West interactions and this revelation of the flow of knowledge from India to the West intrigued me.

I decided, after some thought, that while experimental science was interesting and had done some good work in it, there was a whole area I could make a mark that would bring together my Indian background and the science I was engaged. So, I took the step of leaving experimental science.

During the talk at NCBS, you brought up several books and papers documenting these medicinal plants, and how they were inaccessible to many Indians until translated. Can you expand on this? Was it because of the oral tradition of these systems?

The earliest European works on Indian medicines record folk regional medical practices and not the classical text-based Ayurvedic tradition. In many cases, these European works are valuable records of vanished Indian traditional folk medicines since folk medical knowledge was passed on within families by word of mouth or in family-owned palm leaf manuscripts.

The earliest European works, made for the benefit of European colonists in India, were in European languages: like the 12-volume Hortus Malabaricus that records 700+ medicinal plants of the Malabar region. Also, the later British works on Indian medicine of course are more readily available.

Have there been any recent attempts to codify and document these traditions within the country?

There are attempts by organizations in India to document regional folk medical traditions and databases are now available. The Tropical Botanical Gardens in Kerala I understand has been very active in this area. Also, Traditional Knowledge Innovation of Kerala (TKIK) is attempting to digitize palm leaf manuscripts of the ashtavaidya families of Kerala.

What is the difference between folk and codified Ayurveda medicine? Also, why do people prefer biomedicine over these traditional healing practices today?

Ayurvedic physicians, like the ashtavaidyas, were trained according to the classical texts of Ayurveda by physicians whose learning was based on text-based codified medicines. These scholar physicians are, of course, the most scholarly of traditional medical practitioners. I started my inquiry into traditional medical practices through extensive interviews with three of the most important scholar physicians of the classical ashtavaidya tradition, including the late Olassa Chiratamon Narayanan Mooss.

But I knew from personal experience that a whole other realm of therapies based on folk medicines existed. I extensively interviewed a Carmelite monk physician, Br. Anthony Panakkal, is famous for his knowledge of poison therapy. I followed some of his patients who were sent to him by biomedical physicians, for specific therapies dealing with wound healing from poisonous snakebites. He had an extensive medicinal plant garden and prepared all his own medicines according to the nature of the poison he was dealing with to great effect.

I also interviewed a tribal healer in Attapaddy, and others known for their practice specific to different disease areas and learned that these practices were complementary and covered different aspects of everyday health care.

Today, biomedicine is so prominent, and the potential of traditional medicine especially single plant-based folk medical therapies is on the decline. Many factors influence why we choose biomedicine today. Traditional medical therapies often come with restrictions of diet and lifestyle, where you have to observe certain practices while undergoing treatment; dietary restrictions, for instance, and also traditional medical therapies are often slower acting.

I remember Olassa ashtavaidya, telling me that the healing process had 4 pillars: the medicine, the physician, the patient, and the lifestyle condition. All of those were required for the healing process. It is a complex process as you have to modify your body and behaviour for wellness. Many people don’t have the interest, time, and commitment, so they migrate toward taking potent medicines.

However, there are some attempts to integrate the two. The Arya Vaidya Sala Kottakkal (AVS), for instance, is one institute in India that has managed to practice, side by side, biomedicine and Ayurvedic medicine. They have a strong program to integrate the two ways of healing. Also, today, most Ayurveda diagnostics are based on biomedical diagnostics with the disease being interpreted in biomedical terms.

One of the things you have spoken about extensively, and curated several exhibitions around, is the links between colonisation and Indian traditional medicine. Can you tell us more? What made Indian traditional medicine so powerful?

One of the reasons Indian medicines were powerful is that the knowledge of the healing properties of plants goes way back: the Vedas for example refer to, ‘the herbs, the firstborn of the gods’ and to the healer, ‘the demon killer and the plague dispeller’. Medicines from India were known all around the world, even as far back as the first millennium.

I think it probably has a great deal to do with tropical biodiversity and the inherent nature of knowledge development in the Indian subcontinent. These plants may have had particularly powerful small molecules due to environmental conditions unique to the tropics, to protect themselves. It is interesting to note that fifty of the most commonly used single-molecule drugs, beginning with aspirin, were originally derived from tropical plants, and there are many more waiting to be discovered.