The recent passing of the ‘godfather of British blues’, John Mayall, marks the closing of an extraordinary chapter in British music history. His 1966 album, Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, was a pivotal moment between the initial blues scene that produced The Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann and The Yardbirds and the post blues-boom era of Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Fleetwood Mac.

But how did the blues arrive in the UK in the first place and what made so many young musicians fall under its spell to the point that it changed the make-up and sound of music throughout the world?

To answer these questions we need to travel back to the late 1930s where, in the United States, an interest in early jazz and blues pioneers began to gather momentum. Both genres, still intrinsically linked at that point, had evolved at a startling rate since the birth of the recording industry.

Pop music of the day was ruled by a combination of swing-era big bands and balladeers, or ‘crooners’ such as Bing Crosby. Blues had somewhat fallen behind and continued to be sold almost exclusively to black record buyers.

However, a young generation of white fans were discovering the music through the work of white musicians that had absorbed the style of those early black innovators.

This so-called ‘revivalist’ movement was primarily led by father-and-son ethnomusicologists John and Alan Lomax who travelled throughout the US (and many other countries) gathering ‘field recordings’ and interviews with as many folk and blues musicians as they could find. Their work, heroic as it turned out, was an attempt to create a timeline linking music harking back to slavery with the pop music of the day.

Of particular interest to this story is that they attempted to track down Robert Johnson in 1941, only to discover that Johnson had already passed away. Locals recommended Muddy Waters as someone they might like to meet.

At the time Waters was working on a farm, but realising that there was fresh interest in his music decided – for the second time – to pursue music full-time. For Muddy Waters, the rest is history.

Later into the 1940s a revival also started for traditional jazz forms. By that time, jazz had experienced the bebop revolution, which led many to look back at the early New Orleans artists that had started the jazz ball rolling around the turn of the century. The music of those old-timers still had its roots firmly in the blues leading the two genres to effectively have the same set of new fans.

Many of these jazz and blues innovators had given up music as a profession by this time. They were left behind stylistically as developments in the music rendered them old-fashioned and passé. Suddenly, with this renewed interest in their music, they were back on the road and in the recording studios.

The British scene

In Britain, from the late 40s until the arrival of The Beatles, there occurred the first British musical ‘boom’. Existing side by side with the burgeoning rock ’n’ roll scene, the ‘trad boom’ was huge with bands led by Ken Colyer, Humphrey Lyttelton and Chris Barber, among others, filling concert halls and clubs with eager teens finally having a music to call their own.

Britain went skiffle crazy with bands forming everywhere up and down the country, but most famously in Liverpool…

As youngsters themselves, they had also fallen under the spell of the Lomax recordings and featured folk, blues and spirituals arm in arm with their trad jazz tunes at gigs and concerts.

Jazz trombonist (and bassist) Chris Barber led a band with trumpeter Ken Colyer at the end of the ’40s, and hearing of a young guitarist called Anthony Donegan, invited him to audition. Still a teenager, Donegan joined the band and brought with him his folk and blues influences, which began to be featured as part of the band’s set.

Anthony soon changed his name to Lonnie Donegan and quickly became a hugely popular and influential part of the revival scene in Britain. The name change was inspired after Donegan heard 1920s blues maestro Lonnie Johnson in concert in the early 50s. These interval sets performed by Donegan became known as the ‘skiffle break’ and introduced British audiences to the music of Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie among others.

Such was Lonnie’s popularity that by 1954 he’d made several recordings. In that year he recorded one of the most important records in British music history with his cover of Leadbelly’s Rock Island Line.

Originally part of a Chris Barber 10-inch LP, Rock Island Line was eventually released as a single at the end of 1955. The B-side was John Henry, which Donegan had heard from Woody Guthrie’s recording.

By early 1956 it had reached the Top 10 in the UK, but perhaps more significant is the fact it also made the Top 10 in the USA. The seeds for the subsequent British Invasion had been sown!

It was the record that made an entire generation of fledgling musicians believe they could do the same. These youngsters realised they could make music with little or no training and with cheap, often homemade equipment. It was a seismic shift in musical tastes that foreshadowed the punk explosion of the 1970s.

Hooked on skiffle

This was post-war Britain, still on its knees economically. Coincidentally, wartime rationing finally ended in 1954, the year that Donegan recorded Rock Island Line. Musical instruments were expensive and few could afford the luxury of owning one.

Britain went skiffle crazy with bands and clubs forming everywhere up and down the country, but most famously in Liverpool where a skiffle group called The Quarrymen had Rock Island Line as a focal point of their shows. Those youngsters were later to change their name to The Beatles, but that’s a whole other story…

Realising the commercial potential and cultural significance of this wave of interest in folk and blues, Chris Barber set about inviting some of the originators of the music to the UK to take part in his touring schedule.

The first artist to appear in the UK courtesy of Barber was a true icon: William ‘Big Bill’ Broonzy. Broonzy was a virtuoso guitarist and vocalist who released a string of popular and influential records in the 1930s.

As part of the initial revivalist movement in the US, in 1938 and 1939 producer John Hammond (who brought the likes of Billie Holiday and Bob Dylan into the public eye) staged a pair of concerts at New York’s Carnegie Hall entitled From Spirituals To Swing.

Hammond’s success in educating the so-called sophisticated New York audience to what they had previously considered ‘primitive’ music was a big achievement for its time and paved the way for African American artists to be seen for the exceptional artists that they were.

The shows featured, in chronological order, gospel groups, blues, traditional New Orleans jazz and the top swing musicians of the day such as pianist and bandleader William ‘Count’ Basie.

To fulfil the folk-blues element of the show, Hammond had wanted Robert Johnson to perform, only to discover – as the Lomaxes did – that Johnson had passed away. Broonzy was drafted in to take his place.

As for Robert Johnson, despite his unimpeachable status today, he was a relatively obscure artist during his lifetime in comparison to Broonzy. Jumping on the revivalist bandwagon, the record label Columbia rediscovered Johnson’s recordings, which had been languishing in their vaults for more than two decades.

Re-released on 12-inch LP under the title King Of The Delta Blues Singers in 1961, at the height of the first wave of the blues boom, Johnson’s place as a genius was finally realised. The album’s influence over a generation of young blues fans cannot be overestimated.

Broonzy’s tour of the UK was the first opportunity for British audiences to see and hear the ‘real deal’, although it wasn’t without some controversy. It’s worth noting that blues musicians were, at that time, defined by their recorded output. Labels were not interested in anything but blues from artists such as Broonzy, despite the fact that his shows also featured Tin Pan Alley ‘standards’ alongside folk and even pop songs.

When Broonzy presented his regular show in Britain, he was dressed in a sharp suit and went through his entire repertoire. Audiences were shocked with some even accusing Big Bill as inauthentic.

Quickly realising what was going on, Broonzy changed his set to purely folk-blues and spirituals and, incredibly, now dressed in dungarees and wearing a straw hat, ticket-buyers were ‘satisfied’…

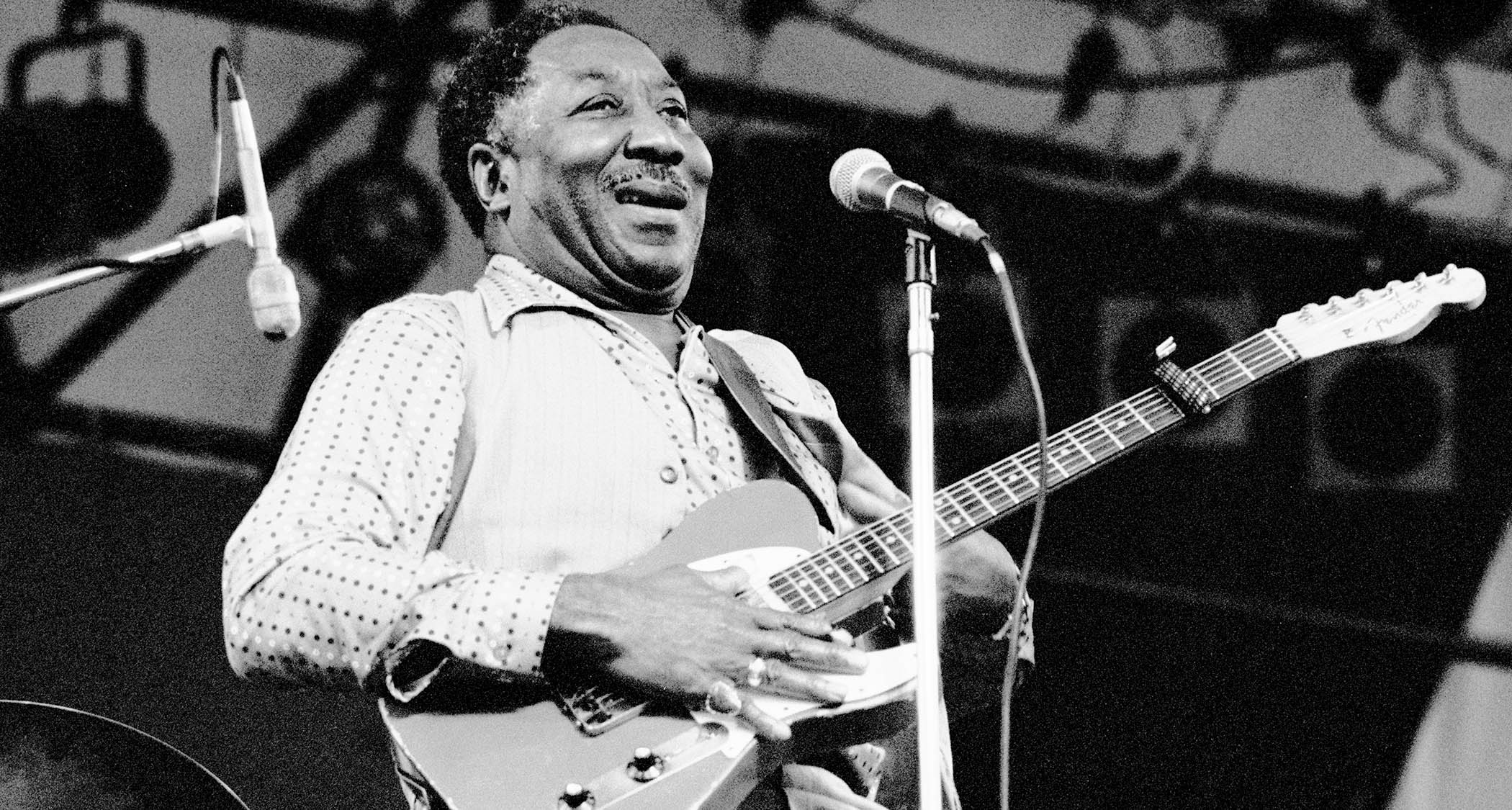

Despite this initial setback, the tour was a huge success and paved the way for many other artists, by now neglected in the US, to embark on European tours. Barber set up many other tours including the incredible duo of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, but the most explosive and revolutionary visit was the 1958 tour featuring none other than Muddy Waters.

Uncharted territory

History hasn’t recorded whether Barber knew what he was letting himself in for when Muddy Waters arrived in the UK armed with a Fender Telecaster. Perhaps he was expecting Muddy to perform his Delta-style country blues on the tour?

This tour truly represents a pivotal moment in music history. It could even be argued that rock itself would have taken a different path if Muddy hadn’t got on stage and plugged in for his 1958 tour.

Fans in the UK still saw blues as an ingredient of jazz in 1958. They saw it as a primitive folk form and hadn’t yet heard the urban version of blues that was emanating from Chicago in the late 1940s.

Muddy’s music had evolved from the Delta and was now raw, gritty and loud. Audiences had simply never heard anything like it before but, importantly, neither had a group of young pretenders namely Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger and Eric Clapton, among scores of others. The early influence of skiffle seemed old-hat overnight, with Waters’ tour spawning hundreds of new, dedicated blues clubs across the country.

However, Muddy’s 1958 tour wasn’t the first time UK audiences had heard electric blues guitar. That honour goes to Sister Rosetta Tharpe who toured with Chris Barber a year earlier in 1957, armed with a Gibson Les Paul Goldtop.

Despite her overdriven guitar sound, Tharpe’s music was heavily focused on gospel and spiritual songs. What made Waters’ tour arguably more influential was the fact he played the type of heavy blues that continues to form the DNA of rock music to this day.

Blues bonanza

As the blues boom gathered pace, promoters rushed to sign up as many African American blues artists as they could find. Visits across the Atlantic quickly evolved into package tours, effectively a travelling festival. By the early 1960s an organisation called the American Folk Blues Festival was in full swing, bringing an incredible line-up of artists on tour to Europe.

Along with Waters and Tharpe, the likes of John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker, Otis Rush, Big Mama Thornton (who performed the original version of Hound Dog), Lightnin’ Hopkins, Buddy Guy, Koko Taylor, Willie Dixon (his song You Need Love morphed into Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love) and Sugar Pie DeSanto, and a wide host of others, regularly toured on this side of the Atlantic through the 1960s and beyond.

In 1957, harmonica player Cyril Davies and multi-instrumentalist Alexis Korner formed the London Blues and Barrelhouse Club. Initially a skiffle venue, it also hosted many of the visiting American blues artists that Barber was promoting.

The next year, in response to hosting the Tele-wielding Muddy Waters and growing tired of the skiffle craze, the pair formed the now infamous group Blues Incorporated. Both Korner and Davies recognised that the future was electric, but found their new, loud and raucous music was too much for the club’s clientele.

By 1961 they had relocated their club to Ealing in West London and the umbilical cord between traditional jazz, skiffle and blues was finally cut as the Ealing Blues Club was the first establishment dedicated to electric blues. Things would never be the same again.

A new generation

Korner and Davies had first worked with Chris Barber back in 1949 and recorded with him in the mid 1950s, so they were already a feature on the trad jazz, skiffle and blues scenes. Each of those three strands of African American music had existed side by side throughout the 50s in the UK as though waiting for one of them to break away. The introduction of the amplified guitar served as the fuse that caused the explosion.

The Ealing Blues Club had initially opened as a jazz venue in 1959. Arthur Wood, Blues Incorporated’s vocalist and, incidentally, the brother of Ronnie Wood, suggested the venue to Korner and Davies and it soon became the go-to place for the increasing number of young blues musicians and enthusiasts in London.

They took traditional blues and rock ’n’ roll elements and cranked them through Vox or Marshall amplifiers . Then, by the mid-60s, another split to the musical atom started to take place

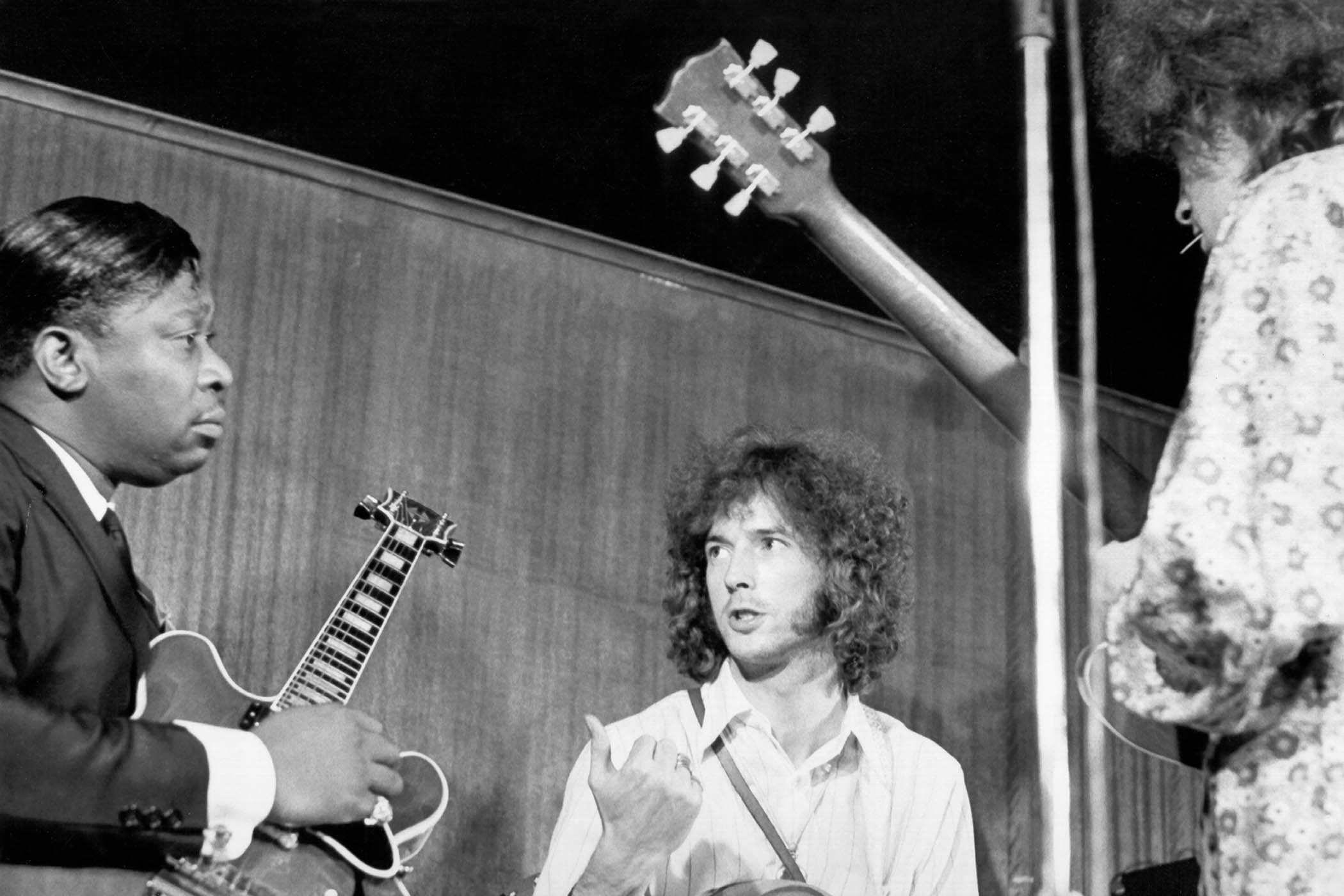

Among those in regular attendance were Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker and Eric Clapton who were later to become Cream. Graham Bond, Rod Stewart, Paul Jones, Manfred Mann and Eric Burdon were among many others frequenting the club.

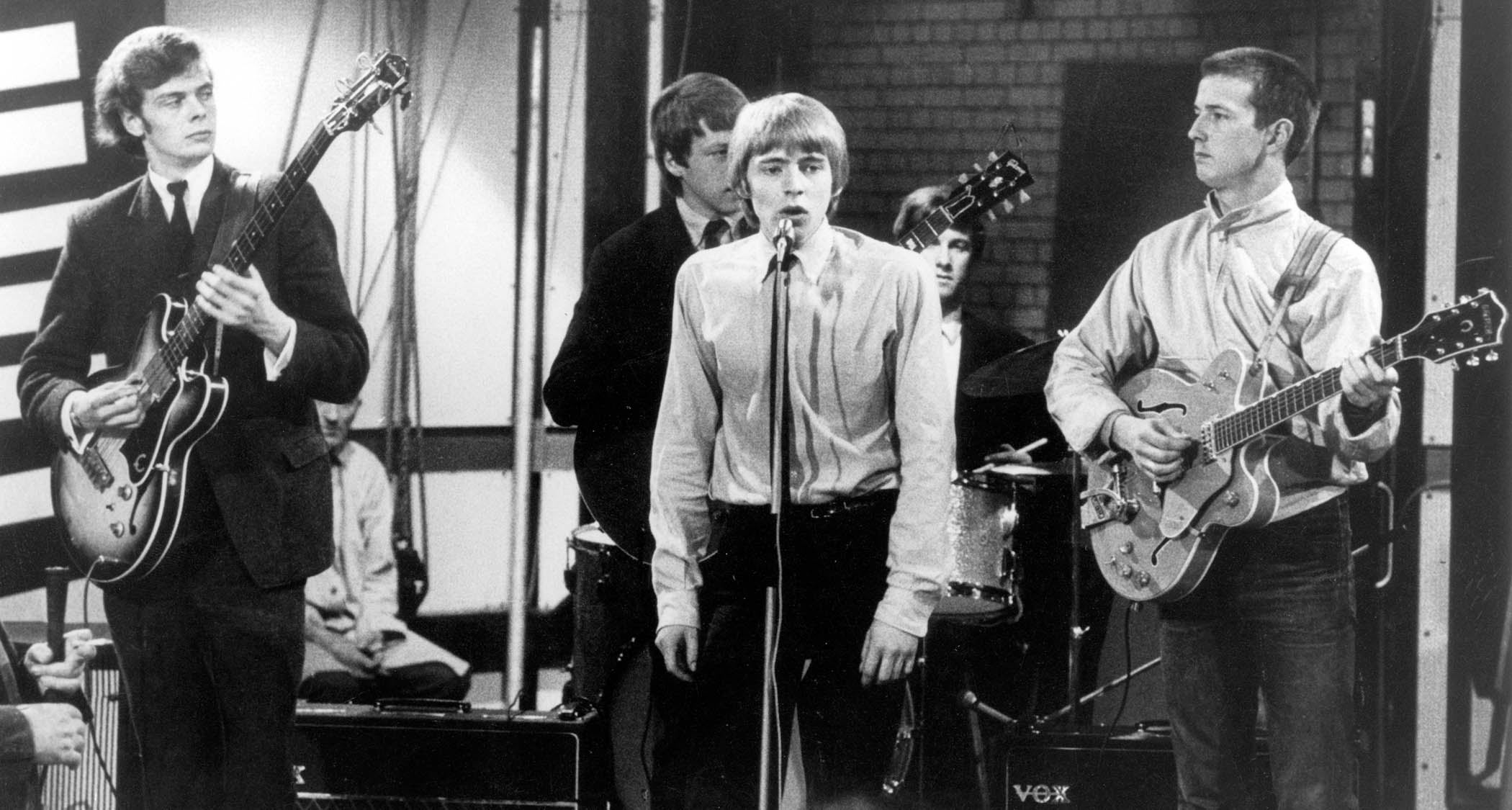

Perhaps most famously, the Ealing Blues Club is the venue where in 1962 Charlie Watts, Brian Jones, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger first met. In July of that year, this line-up played their first gig at London’s Marquee Club, with the Ealing Blues Club’s stage a key part in their early performances.

On Alexis Korner’s advice, John Mayall moved to London from Manchester in 1963, formed his band The Bluesbreakers and started playing at the Marquee.

Their original guitarist Bernie Watson, a sadly now-forgotten cog in the wheel, came over from Cyril Davies’ group, the R&B All-Stars, which Davies formed shortly after his departure from Blues Incorporated. The Bluesbreakers’ next guitarist Roger Dean was present when the band supported John Lee Hooker on his 1964 UK tour.

1964 was also the year that both The Rolling Stones and The Beatles first toured America. These early tours set off the ‘British Invasion’ that saw these young, white British kids effectively ‘selling coal to Newcastle’.

Both groups were staggered to discover their heroes were neglected, and sometimes forgotten, in their own countries. Both groups were a culmination of a decade’s worth of musical development in the UK with The Beatles growing directly from skiffle and The Stones from blues. Both owe a lot to the foresight of people such as Chris Barber and Alexis Korner.

Around the same time bands including The Who, The Animals, The Kinks and The Yardbirds were taking the UK, and then the US, by storm.

All were under the spell of those mid-50s blues masters who had travelled to Britain, and each had their own ideas on where to take the music. They took traditional blues and rock ’n’ roll elements and cranked them through Vox or Marshall amplifiers. Then, by the mid-60s, another split to the musical atom started to take place.

Cashing in

The point of division was between those that saw dollar signs and those that felt the music was losing its blues roots. Eric Clapton had joined The Yardbirds in 1963 when the group were almost exclusively disciples of the type of Chicago blues they’d heard Muddy Waters perform in 1958. By 1965, and with inevitable record company pressure, they’d recorded and released the hit single For Your Love.

Clapton was unhappy with the commercial path the band was taking and left shortly after the song’s release. Feeling the need to stay true to his love of blues, Eric joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and recorded one of the most staggering albums in guitar history. As for The Yardbirds, they had no need to worry about Clapton’s departure – they had Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page onboard in no time!

And so it was with a lot of bands that had emerged from the initial blues scene. Most followed a path that strayed from the blues with The Rolling Stones arguably managing to maintain their own blues roots more than the others.

New influences were making their way over from the States at the same time. Soul and Motown sounds were becoming popular but kept only tentative links to blues. Artists such as James Brown were taking soul in another direction and inventing funk in the process.

All made a big impact on British music and threatened to kill off the hardcore blues scene were it not for the likes of Alexis Korner and John Mayall who remained steadfastly loyal to the blues.

Had they decided to ‘sell out’, the British Blues Boom might have ended there. But with the release of the iconic ‘Beano’ album, a new strand of blues was created that paved the way for groups such as Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Fleetwood Mac and Black Sabbath to conquer the 1970s. Each of these put their blues roots before commercial pressures and managed to find huge audiences as a result.

Out of obscurity

The story of the British Blues Boom isn’t without its ironies. Artists such as Buddy Guy, BB King and others enjoyed a whole new career path as a result of it. Many great and important American blues musicians struggled with the advent of rock ’n’ roll, a genre that stemmed directly from blues.

Many had to give up music as a full-time job and many were ‘rescued’ from obscurity after a bunch of British lads took American music back to where it had originated and reminded Americans that many of those originators were still alive and kicking.

But perhaps the most poignant part of the story is that of Jimi Hendrix. An obvious supreme talent who, had he never been ‘discovered’ playing a small club in New York in 1966, would still have been able to boast an impressive CV.

He’d already played and toured with a veritable who’s-who of American soul and rock ’n’ roll stars such as Little Richard, The Isley Brothers, Ike and Tina Turner, Wilson Pickett, Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson, but he was yet still unnoticed for his genius and was always constantly broke financially.

When Chas Chandler, bassist from The Animals, saw him for the first time he couldn’t believe that Hendrix hadn’t been signed up for stardom. Recognising that the music scene in Britain that had been kickstarted by Jimi’s predecessors might be the answer, he soon had him on a plane to London to find out.

Within days Jimi was being hailed as a messiah by every blues and rock star that saw him play. Here, suddenly, was a genuine, authentic blues musician of their generation! The British Blues Boom had unwittingly created a space for this unknown American to find his voice. Jimi’s arrival gave British music a shot of adrenaline that it wasn’t primed for.

It would likely never have happened for Jimi Hendrix in his native country, yet within nine months he was back in the States as a superstar, leaving Americans wondering how they could have missed out on him before he’d left.

It definitely wouldn’t have happened for Jimi in the UK had the interlinking strands of traditional jazz, blues, skiffle and rock ’n’ roll not created the perfect platform for him to ride in on.

As it gathered pace in pubs, clubs and dance halls, it was inevitable that the surviving pioneers would be sucked in eventually, where, from there, it took on a life of its own

It was a scene that originated from an interest in folk blues and early jazz going back to the 1930s before crossing the Atlantic – constantly being fuelled by small groups of enthusiasts huddled around a 78rpm record player listening to whatever discs they could lay their hands upon.

As it gathered pace in pubs, clubs and dance halls, it was inevitable that the surviving pioneers would be sucked in eventually, where, from there, it took on a life of its own in the ensuing decade. A generation of young musicians were transfixed, and, without realising it at the time, forged a new music for the world – a music that was revolutionary and pioneering in its own right yet never lost its respect in those who had created it.