Plants existed on Earth for hundreds of millions of years before the first flowers bloomed. But when flowering plants did evolve, more than 140 million years ago, they were a huge evolutionary success.

What pollinated these first flowering plants, the ancestor of all the flowers we see today? Was it insects carrying pollen between those early flowers, fertilising them in the process? Or perhaps other animals, or even wind or water?

The question has been a tricky one to answer. However, in new research published in New Phytologist, we show the first pollinators were most likely insects.

What’s more, despite some evolutionary detours, around 86% of all flowering plant species throughout history have also relied on insects for pollination.

How to move pollen

The timing of the evolution of the first flowering plants is still a matter of debate. However, their success is inarguable.

Around 90% of modern plants – some 300,000-400,000 species – are flowering plants, or what scientists call angiosperms. To reproduce, these plants make pollen in their flowers, which needs to be transferred to another flower to fertilise an ovule and produce a viable seed.

Small and highly mobile, insects can be highly effective pollen transporters. Indeed, recent research on fossil insects shows some insects may have been pollinating plants even before the first flowers evolved.

Most of today’s flowering plants rely on insects for pollination. The plant’s flowers have evolved to attract insects via colour, scent and even sexual mimicry, and most reward them with nectar, pollen, oils or other types of food, making the relationship beneficial to both parties.

Some flowers, however, rely on other means to transport their pollen, such as vertebrate animals, wind or even water.

Which kind of pollination evolved first? Were insects there at the beginning, or were they a later “discovery”?

While early evidence suggests it was probably insects, until now this has never been tested across the full diversity of flowering plants – their full evolutionary tree.

A family tree

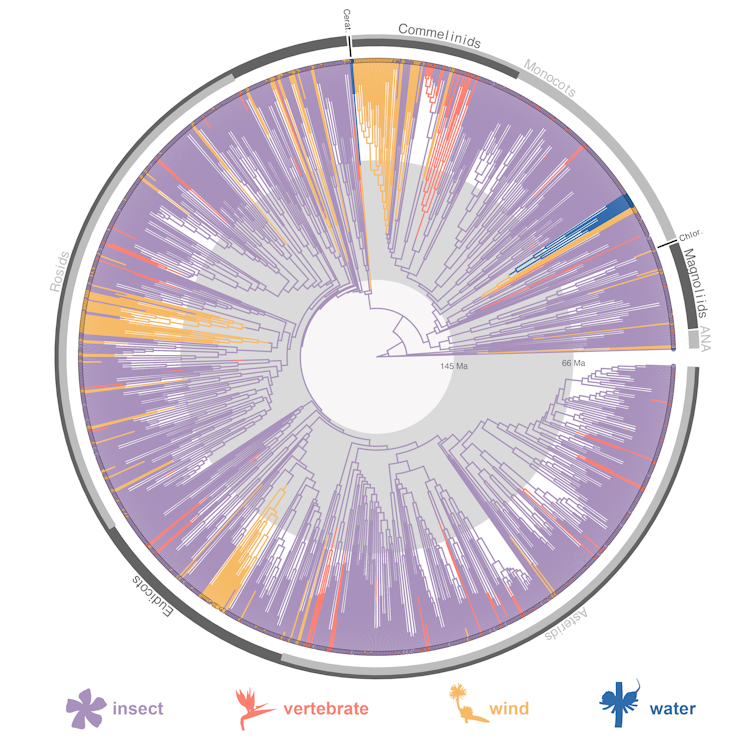

To find an answer, we used a “family tree” of all families of flowering plants, sampling more than 1,160 species and reaching back more than 145 million years.

This tree shows us when different plant families evolved. We used it to map backwards from what pollinates a plant in the present to what might have pollinated the ancestor of that plant in the past.

We found insect pollination has been overwhelmingly the most common method over the history of flowering plants, occurring around 86% of the time. And our models suggest the first flowers were most likely pollinated by insects.

Birds, bats and wind

We also learned about the evolution of other forms of pollination. Pollination by vertebrate animals, such as birds and bats, small mammals and even lizards, has evolved at least 39 times – and reverted back to insect pollination at least 26 of those times.

Wind pollination has evolved even more often: we found 42 instances. These plants rarely go back to insect pollination.

We also found wind pollination evolved more often in open habitats, at higher latitudes. Animal pollination is more common in closed-canopy rainforests, near the equator.

What kind of insects were the first pollinators?

If you think of a pollinating insect, you probably imagine a bee. But while we don’t know exactly what insects pollinated the first flowering plants, we can be confident they weren’t bees.

Why not? Because most evidence we have indicates bees didn’t evolve until after the first flowers.

Read more: Flies like yellow, bees like blue: how flower colours cater to the taste of pollinating insects

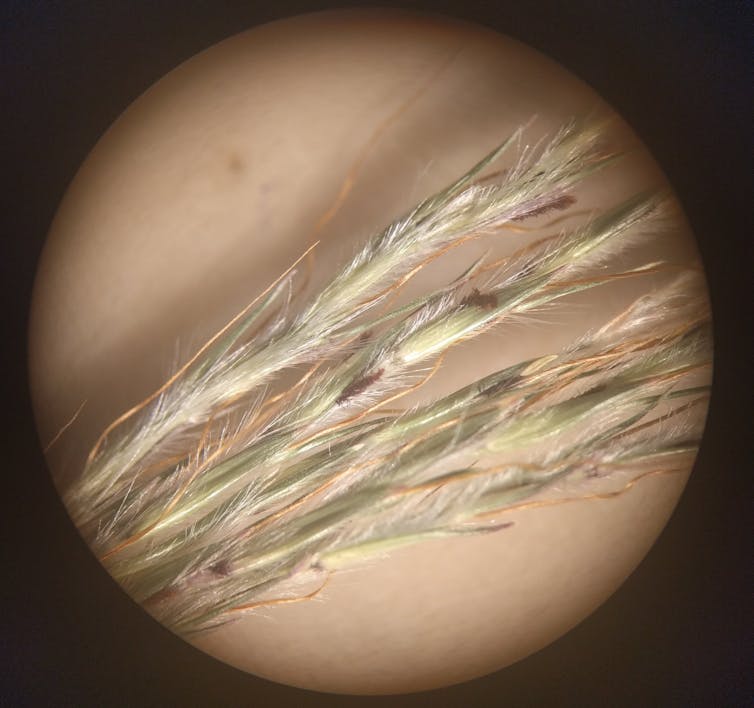

So what do we know about the pollinators of the first flowering plants? Well, some early flowers have been preserved as fossils – and most of these are very small.

The first flower pollinators must have been quite small, too, to poke around in these flowers. The most likely culprits are some kind of small fly or beetle, maybe even a midge, or some extinct types of insects that have long disappeared.

If only we had a time machine we could go back and see these pollinators in action - but that will require a lot more research!

Ruby E. Stephens receives funding from the Australian Government's Research Training Program.

Hervé Sauquet receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Australian Research Data Commons.

Lily Dun received funding from Australian Research Data Commons.

Rachael Gallagher receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

Will Cornwell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.