A few days after her 18th birthday, Valerie Jean Blackett walked from Victoria Barracks to Central Station as an enlisted woman, bound for service as a gunner protecting the Newcastle Harbour from encroaching Japanese submarines and aircraft.

She remembers them looking like a gaggle of peacocks walking down the streets of Haymarket, some in high heels, some in flat shoes, some wearing hats, and "everyone calling out 'you'll be sorry!' all the way down to Central".

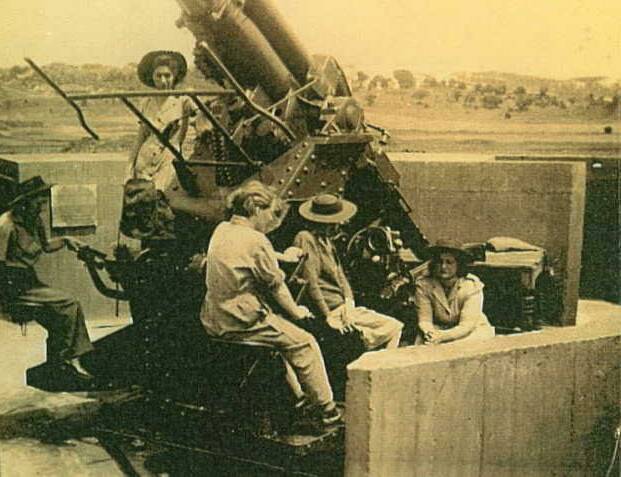

Val and her fellow veterans had, by one sergeant's estimate, one of the most important jobs in the country - protecting the BHP steelworks and Newcastle Harbour at a time when one in three of the 39 ships sunk by Japanese submarines in World War II were destroyed on the stretch of coast between Newcastle and Sydney. But the men didn't see it that way.

When Val topped her mathematics class during her training, they told her to "go back to kindergarten". When she and the other gunners in her unit were tasked with guiding the aiming apparatus for the boys who manned the guns, their training pilots all called in sick. War was a boys club, but Val and her fellow soldiers had a country to serve. Boy's be damned; there was work to do.

Her father was a gunner in the Somme; so were his two brothers and five first cousins.

"When he found out I was a gunner, too, he called everyone he knew to tell them," Val says in an interview recorded a little more than two years ago for Stories of Our Town, a local filmmaking project directed by Glenn Dormand.

Val's interview was originally intended for the project's 'Fortress Newcastle' documentary, which delves into the history of the protection of Newcastle's industries during the Second World War. Newcastle was an industrial hub of the defence industry; it made ships and repaired them, producing guns, uniforms, helmets, and aircraft components. The project noted that the protection of those assets was equally complex.

Valerie Blackett is now almost 100 years old, and on Thursday, she was set to lead the Anzac Day march in Sydney. Mr Dormand told Topics this week that her story is the story of Newcastle.

"Everyone was abusing them," Mr Dormand said, "They were angry at her, which is amazing. Rather than cheering her heroics, it was 'oh, you bloody idiots'."

Mr Dormand said Val's story had sat in the archive since the release of Fortress Newcastle, but as Anzac Day approached again, the project, which has sought to capture the city's history from those who lived it, is releasing the full tape.

Val's service in protecting the Hunter was operating the 'heightened range finder'- a telescopic piece of equipment that helped the anti-submarine and aircraft gun emplacements aim and hit their mark. It was "technical" work, as Val described it, undertaken by "the most amazing lot of girls". But in all the valour, there was also fear:

"Absolute fear," Val said, "Most of that was from not knowing what we were up against."

It was meagre digs. Val's unit of about 30 servicewomen camped on the sand inside a ring tank traps and barbed wire above their command post buried under Stockton. The meals were potatoes or whatever they could find. Compared to that, Fort Scratchley seemed a luxury. But the locals took them under their wing and would bring foodstuffs and cakes.

"The people were just unbelievable," Val says. "I just couldn't believe people were absolutely wonderful to us."

Val was sent to Fort Wallace and trained to use the first radar to be installed in the country, but it was there that she suffered a bullet wound to the head when a live round found its way into a boiler over which she was working. She was hospitalised and later had surgery to remove the round at Greta, and when the bandages were removed, the men of the camp were on hand.

"I said to the nurse, can we [take the bandages off] outside," Val says. "They took the bandages off, and they all said "Marry me!" - I had a hundred proposals of marriage in one day."

Val was ultimately returned to Victoria Barracks in Sydney, where she remained until the end of the war.

"All of my friends have passed away, and I have this relationship with most of their daughters," Val says. "And there, as close to me as their mothers were, we had an amazing lot of women. Absolutely beautiful. I loved them all.

"I think that was the nicest thing that came out of it."