You could call her the mother of Father’s Day.

The late Sonora Smart Dodd launched the celebration of dads in 1910 in her hometown of Spokane, Washington. As a result, she is the one responsible for those annual gifts that run the gamut from embarrassingly silly-looking neckties to kids’ finger paintings crafted with so much love by those tiny hands that they can bring a tear to the eye of even the most stoic father.

It’s a tradition Dodd decided to start as she sat in a Spokane church on Mother’s Day 1909, listening to a sermon about — what else? — Mother’s Day.

“And it bugged her,” Dodd’s great-granddaughter, Betsy Roddy, told The Associated Press in 2017. “She thought, ’Well, why isn’t there a Father’s Day?”

Dodd and her five younger brothers, after all, had been raised by their father after their mother died in childbirth in 1898.

William Jackson Smart became a farmer after fighting in the Civil War. He not only held down both parental roles but did it with “leadership and love,” his daughter always said, and she believed he ought to get some credit.

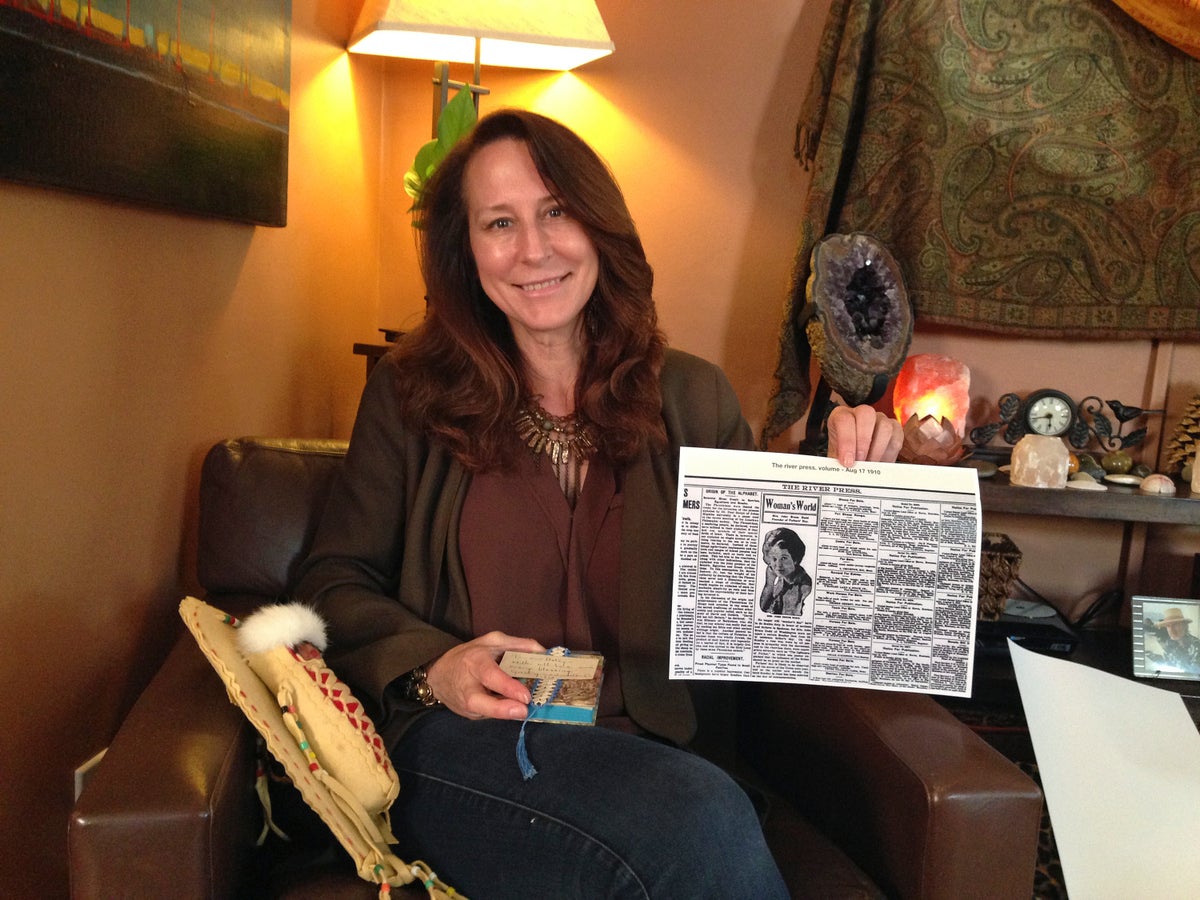

“So she worked tirelessly with the local clergy and got the YWCA on board, and they had their first Father’s Day in Spokane in 1910,” said Roddy, displaying a copy of The River Press of Fort Benton, Montana, which reported on the event.

Although that story predicted the celebration would go nationwide by the next year, Father’s Day was slow to catch on. So much so that Dodd spent the next 62 years lobbying everyone from presidents to retailers for support.

Finally, in 1972, President Richard Nixon declared the third Sunday of June a federal holiday honoring dads. Dodd, who died at age 96 in 1978, had lived to see her dream come true.

A Renaissance woman, the Mother of Father’s Day was a painter, poet and businesswoman, running a funeral home with her husband while raising the couple’s only son, a future father named Jack.

“I take a great deal of pride in that renegade spirit that she clearly had,” said Roddy, marketing director for a large Los Angeles company.

Dodd’s great-granddaughter inherited some of that spirit herself. Raised in Washington, D.C., she earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Penn State before heading to Europe for several years of backpacking between studies at Vienna’s Webster University, where she earned a master’s degree in international business.

Moving to Los Angeles decades ago, she found her niche here in marketing and stayed, eventually moving into a Craftsman-style home on the city’s west side, where she lives with her two dogs.

The only child of an only child and recently widowed after 24 years of marriage, Roddy never had children of her own. That not only leaves her with the title of Great-Granddaughter of Father’s Day but also assures she is the last direct descendant of the holiday’s creator.

Although she’s always been well aware of that legacy, she’s never talked about it publicly until now.

She began to get more involved after MyHeritage.com, the company that helps people trace family histories, asked if she knew her family’s story.

Learning that she did, MyHeritage dug up historical documents about Dodd that Roddy says even she and her mother didn’t know existed. They are considering eventually turning over some of their artifacts to a museum.

As a child, Roddy said, she loved her great-grandmother deeply, visited her every year and treasures the poems, books and notes she gave her, including one welcoming her to the world on the year she was born. She still keeps it, in pristine condition, in a small box in her home.

Still, as a child, Roddy says, she took Father’s Day largely for granted, concluding the elaborate celebration, including the special card for her great-grandmother, was just something her family did. Even as an adult, she’s generally kept quiet about being the ultimate Father’s Day insider, leaving it to her mother to spread the word.

But no more.

“It’s time for me to pick up the baton and carry it proudly,” she says with a smile. “I’m the last direct descendant. The legacy is here, which is an honor.”

___ This story was first published in 2017. Rogers retired from The Associated Press in 2021.