Lagos, Nigeria – Last May, Nigeria’s ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) announced Aishatu “Binani” Dahiru as the winner of the governorship primary in the northeastern state of Adamawa, making her the only female flagbearer of any mainstream party in the governorship and state assembly elections.

The 51-year-old politician could also make history as the first elected female governor in Africa’s largest democracy on Saturday, when only 24 of the 416 candidates vying for office are women.

Dahiru could be announced governor-elect as early as Sunday afternoon if she can defeat 13 other opponents, including the incumbent Governor Ahmadu Fintiri, who is seeking re-election under the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP).

Getting the ticket was no small feat.

In the primaries, Dahiru fended off competition from male political veterans including former anti-corruption chief and ex-presidential aspirant Nuhu Ribadu and Jibrilla Bindow, the immediate past governor of the state. Months after the primary, a state court nullified the result due to irregularities before a higher court later quashed the judgement.

The election proper presents a different challenge for Dahiru, a serving senator since 2019 and previously, a one-term member of the House of Representatives. But pundits say it could usher in change in what remains a conservative society.

“Coming from an ultraconservative region, many assume that a woman has no place running for the office she is,” Fakhrriyyah Hashim, a former fellow of the Africa Leadership Centre and convener of the Arewa MeToo movement, told Al Jazeera. “They appropriate instead her inability to lead men in prayer to her supposed inability to lead a society in governance.”

Religious scholars have openly preached against her candidacy. Across the region, a deadly 13-year insurrection by Boko Haram, which outlaws Western education and has abducted women and children, continues.

But her supporters, especially the rural working class and women, remain unfazed. Residents say for years, she has been widely involved in philanthropic efforts across the state, helping low-income households.

“This is the path Aishatu has laid out a long time ago,” Yasmin Buba, an advocate for girls in Yola, the Adamawa capital, told Al Jazeera. “Unlike other politicians who get to the communities through stakeholders, Aishatu interfaces with the people directly.”

Building a base

The APC’s guidelines that two of every five delegates elected from each ward, the lowest tier of the electoral structure in Nigeria, must be women, worked in Dahiru’s favour during the governorship primaries. Already popular with women across the state, many of the delegates identified with her ambition.

It also helped that Abuja gave its support. She was reportedly backed by the presidency as well as by former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, the PDP presidential candidate in the 2019 and 2023 elections.

Still, Dahiru has built a formidable political machinery over 20 years that many say could spur her to victory if there is high voter turnout. A businesswoman and trained engineer, she became active in politics after returning from her studies in the United Kingdom.

Over the last decade, her reputation has skyrocketed.

In 2011, she ran for election into the House of Representatives under the People’s Democratic Movement (PDM) to represent the Yola North/Yola South/Girei federal constituency. Four years later, she moved to the All Progressives Congress in 2015 after Muhammadu Buhari defeated then-incumbent Goodluck Jonathan to become president.

There, Dahiru lost her bid to get into the Senate before finally being elected in 2019 as one of Adamawa’s three senators and the only female from the North in that electoral cycle.

She has promised to harness the agricultural capacity of the state in addressing poverty and inequality. She has also presented herself as a defender of women’s rights to education and the right to vote and run for office.

“During my campaigns what I told those women was that if they voted for Binani, they would be doing their children a favour,” Dahiru said in one interview. “I told them that: “If you have a daughter, you will be doing her a favour by voting for me; you will be doing that favour to a sister and to some extent your mother.”

“I will give the issue of women and youths, and especially the girl child, preferential treatment,” she added.

To counter Dahiru’s appeal among women who form a large part of her political base, Fintiri picked a female running mate.

Female representation in politics

Nigeria has had a female governor once, but she was not elected. In November 2006, Virginia Etiaba became governor of Anambra when the incumbent Peter Obi was impeached. She relinquished the seat in February 2007 when a court order nullified his removal.

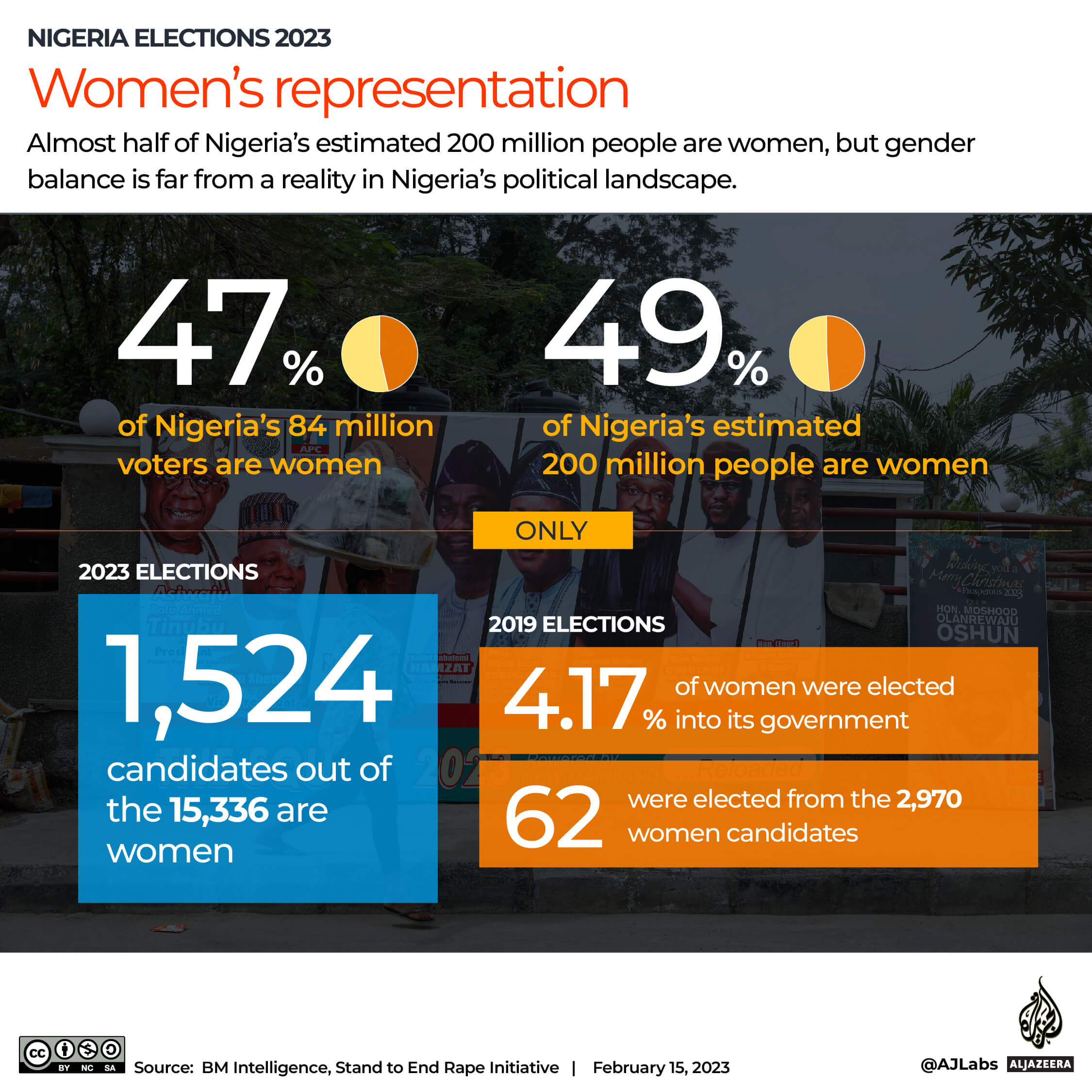

Dahiru’s ascension to the big stage comes as female representation in Nigerian politics is declining. The number of women in federal parliament has consistently dropped since 2011. In the March 2023 vote, the figure dropped further from 21 of the confirmed 423 seats, to 15.

This comes as other African countries are increasing women’s representation in politics, said Elor Nkereuwem, researcher of gender and social movements at the John Hopkins University.

“The truth is women have been able to gain those opportunities because of legislation that has mandated quotas for women,” she said.

Last year, Nigeria’s parliament rejected five gender bills seeking equality for women, including affirmative action quotas for women in legislature, with members of the male-dominated parliament citing religious and cultural reasons.

“Generally, women leaders tend to be relegated to the periphery because an array of societal contradictions hinders their political journey,” Irene Pogoson, professor of political science at the University of Ibadan, said.

Analysts say a combination of sociocultural norms and a hostile political environment has kept women from occupying top political roles.

But the law has, too.

In 2015, former cabinet minister Aisha Alhassan almost became Nigeria’s first elected female governor after a tribunal overturned the election in nearby Taraba, also in the northeast, only for a higher court to reverse the decision.

An ‘exclusive men’s club’

And while Dahiru’s footprint in her communities is noticeable, critics point out that she sponsored fewer than 10 bills – none of them directly about women – in 12 years in parliament.

“Like most Nigerian politicians, they do not play the ideological battle of ideas that politics is built on. I believe the same is true for Binani. What she does better than most is sell herself and she understands how to play Nigerian politics,” Hashim said.

Still, analysts point out that her journey so far is symbolic of much-needed colour and inclusion in Nigeria’s otherwise murky politics. Whether history will be made remains to be seen, but the broad, cross-party appeal Dahiru has garnered could be the beginning of a new era, they say.

“We should not underestimate the power seeing another woman in such leadership position engenders- because, as role models, they can help broaden the pool of women who can imagine themselves in similar leadership positions,” Pogoson told Al Jazeera.

“If Aishatu wins, women will start seeing that these substantive positions are not an exclusive men’s club,” Nkereuwem said.