Consulting behemoth PwC is in hot water after it was found to have handed big tech companies confidential information detailing how the government planned to tax… big tech.

The leak first came to light two weeks ago when the Tax Practitioners Board released 144 pages of heavily redacted internal correspondence between 53 PwC partners and 14 of PwC’s honorary global clients.

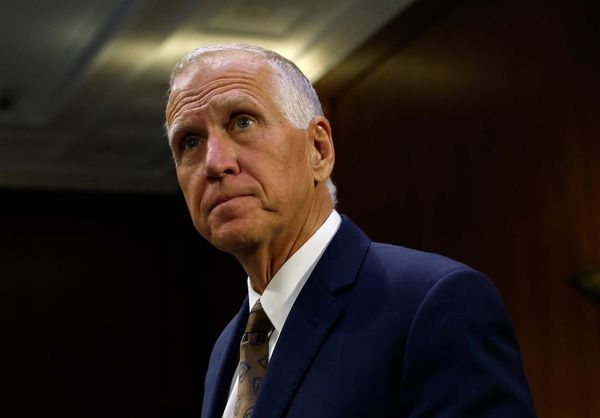

Since then, CEO Tom Seymour has quit, other senior executives have resigned, a senior partner was banned from working in the industry, the firm sent in global senior leadership to start mopping up the Australian mess, an independent investigation was launched, and former prime minister Scott Morrison (never one to be left out) managed to write himself into the story.

Where did PwC go so wrong?

It starts in 2014, when (now former) PwC partner Peter Collins was advising Treasury on how to streamline tax processes for big multinationals, namely tech companies. The name of the game was to bolster the government’s defences against big players dodging tax in Australia, to be done via the introduction of a new Multinational Anti Avoidance Law (MAAL).

Collins then had the idea to share the government’s plans to clamp down on tax avoidance with a cohort of colleagues, who in turn shared the intel with the targets of the tax reforms — predominantly US tech companies. For the price of $2.5 million (in consultancy fees), the PwC collective handed over an instruction manual outlining exactly what the Australian government had in store for these multinationals. It also came with a precise timeline of when these laws would take effect.

In short: big money makers (and lean tax-payers) were given a heads-up on how to jump over (or side-step) the new rules designed exclusively to stop them fox-trotting all over the Australian tax department.

PwC’s reverse-Robin Hood approach also benefited it handsomely, with the intel winning the firm many new “brand-defining” clients. In an email, Collins deemed it an “opportunity to own this space”.

Aren’t consultants paid to give people advice?

Absolutely they are. And big money too.

In the consultancy world, the concept of “conflict of interest” is scarce. Firms can take on multiple clients from the same industry at the same time. In fact, that’s their biggest drawcard — consultants know what everyone else is doing.

But clients come with contracts and it’s not part of their job description to breach that in order to feed and furnish another.

In the case of the tax leaks, Collins signed three confidentiality agreements with the government in order to be admitted as an adviser on the reforms. Documents were provided on a “strictly confidential basis”, but Collins continuously shared documents, updates, plans, proposals (and the list goes on) internally. His only request to fellow PwC partners was that the intel be treated as “rumour and expectation”.

Which PwC clients have been implicated?

PwC put the feelers out to 23 US tech companies that would cop the brunt of the new laws. It’s believed that Apple, Google and Microsoft were among the big names.

From the hot list, PwC landed a hit list of 14 companies. While these are all named in the email exchanges, their names remain redacted. But pressure is mounting to make this information public, along with the names of all the PwC partners involved in leaking intelligence.

Which politicians are piling on?

Labor Senator Deborah O’Neill has led the political charge against PwC. She wants a public-facing exposé on the full scale of malpractice. Most notably: names.

She’s joined by Liberal Senator Andrew Bragg, who has called for an inquiry that looks beyond just PwC. He wants to bring in the corporate regulator for a fully fledged assessment of how accounting firms, particularly those of the “big four” calibre, are policed in Australia.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers was all fury and adjectives when he found out about the “shocking” and “appalling” breach of trust.

As for the Greens, they want a review into the government’s use of big four firms, which includes PwC, Deloitte, KPMG and EY.

What’s PwC got to say for itself?

PwC has taken a softly-softly approach, quietly letting problem staff go and moving others out of leadership roles. The CEO has called it quits, and the international cavalry have been sent in — including legal business solutions leader Tony O’Malley, taking on the task of chief risk and ethics leader for PwC Australia.

Former Telstra chief Ziggy Switkowski will head up an independent review of the company. It will be on O’Malley to action any and all of his recommendations.

Where does Scott Morrison come in?

It appears the former prime minister is attempting an exit strategy from politics, with PwC to play a part. He reportedly had his sights set on an advisory role at the firm, but sadly (for him) this will not be, with sources at PwC telling The Australian that “hiring Morrison would have brought an unacceptable level of reputational risk to the firm” (which is unrelated to PwC’s tax leak problems).