The questions on everyone’s minds as the Aug. 2 trade deadline approaches are where Juan Soto will end up, or if the Angels will part ways with Shohei Ohtani. But what if a GM decided to trade a player for the Phillie Phanatic, or for a couple of Dodger Dogs? It might not be as far-fetched as you think—here’s a look back at some of the strangest trades ever made in baseball history.

One day, two games, two dugouts

One Hundred years ago, the Cardinals and the Cubs swapped outfielders in between games of a Memorial Day double-header.

The morning of May 30, 1922, Max Flack was playing right field for the Cubs at Wrigley Field, then called Cubs Park. Cliff Heathcote was the starting center fielder for the visiting club, which had debuted its iconic bird-on-bat logo two months earlier. In Chicago’s 4–1 win, Flack went 0-for-4 and Heathcote went 0-for-3, but their general managers must have seen something they liked in the opposing outfield. At the conclusion of the game, they announced a 1-for-1 trade of the two players.

Both players started the afternoon game in right field for their new clubs. Heathcote went 2-for-4. Flack was immediately placed at the top of St. Louis’s order for the second game, going 1-for-4 and notching an outfield assist at home plate. But it wasn’t quite enough, because the Cubs took the second game too, 3–1. Though the Cubs swept the Cardinals that day, both Heathcote and Flack went home with a win apiece.

The between-game trade seemed to work out for both players. Flack finished his career in St. Louis, retiring as a Cardinal in ’25, and Heathcote spent the next eight years with the Cubs.

Oyster Joe

Joe Martina spent 22 years in organized baseball as a pitcher and shortstop. He won the World Series in 1924 with the Washington Senators, his only season in the major leagues. Born and raised in New Orleans by an oyster dealer father, Martina’s family business landed him the nickname “Oyster Joe” from teammates and sports reporters.

It was fitting, then, that in ’29 Martina negotiated his own release from the Dallas Steers of the Texas League in exchange for two barrels of oysters. Martina reportedly offered one barrel, but the Steers held out for two, and gave the extra to Dallas sportswriters.

The Austin American via Newspapers.com

While not technically a trade, the oyster deal secured Martina his own rights and allowed him to move to the Cotton States League the following season. He suited up for the Lake Charles Newporters and later signed with the Monroe Drillers—no word on whether mollusks were involved in that transaction.

Fowl play

Johnny “Binky” Jones was the shortstop for the minor league Chattanooga Lookouts in 1930 before owner Joe Engel offloaded him to the Charlotte Hornets of the Piedmont League. The return? A 25-pound turkey.

“I figure I outsmarted Joe on this one,” said Felix Hayman, owner of the Charlotte club. “This is the offseason for turkeys and I’ve got plenty right here in my butcher shop.”

The Hunstville Times via Newspapers.com

Engel used the bird to entertain the Southern Baseball Writers Association. He treated the writers to a banquet at Engel Stadium, where they were presented with a turkey and a placard that read “through the courtesy of Johnny Jones.”

Jones was reported to be a holdout for Charlotte the following season, and isn’t listed on any of Charlotte’s future rosters. The Hornets seemed fine without him, going 100–37 in the ’31 season, and fielding a squad that is considered to be one of the best minor league teams of all time. Jones never appeared to return to organized baseball—being traded for poultry might have been a tough one to swallow.

And as for the turkey? “Wonder what the turkey would say about being traded for Johnny Jones,” said Zipp Newman, president of the writers’ association. “Good thing it wasn’t a parrot.”

Hall of Fame-worthy fence

Robert Moses “Lefty” Grove is a member of the 300-win club and led the majors in ERA a record nine times. But before his Hall of Fame major league career began, Grove was traded for a fence.

In 1920, Grove was 20 years old and pitching for the Martinsburg Mountaineers, a Class D minor league team out of West Virginia. The Mountaineers’ home diamond was missing an outfield fence, after it had been blown down by a storm and the club was unable to afford a replacement.

Grove’s 1.68 ERA caught the attention of scouts, including one Jack Dunn, who had previously signed Babe Ruth to his first professional contract. The Mountaineers agreed to sell Grove’s rights to Dunn’s minor league Baltimore Orioles for the sum of between $3,000 and $3,500 (reports vary)—exactly the price of the outfield fence Martinsburg needed.

Kirthmon F. Dozier/USA TODAY Sports Network

Broadcaster for ballplayer

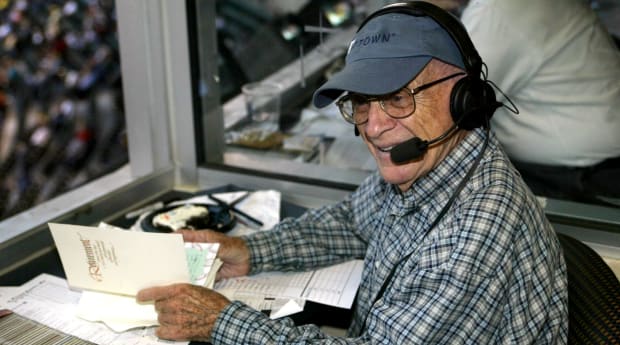

Longtime Dodgers announcer Red Barber had to take a leave from the team in 1948 due to a bleeding ulcer, and GM Branch Rickey found a replacement in Ernie Harwell, then calling games for the minor league Atlanta Crackers. Only one problem: the Crackers wanted a player in return for releasing their broadcaster from his contract.

That’s how Cliff Dapper, then a catcher for the Class AAA Montreal Royals, ended up being the only baseball player ever traded for a broadcaster. Dapper spent one season with the Crackers as a player-manager, and put up a .281 batting average.

Harwell called the Dodgers for a year and spent most of his Hall of Fame baseball broadcasting career with the Tigers. He and Dapper met for the first time in 2002, the year Harwell retired.

Traded for themselves

There are very few trades in baseball that everyone can agree are objectively equal. But there are four players in MLB history that got an exactly even return: themselves. Each of these four players were traded for a player to be named later, which would ultimately turn out to be… themselves.

Catcher Harry Chiti was the first player in baseball history to be traded for himself. Cleveland sent him to the Mets for a player to be named later on April 25, 1962, only to get him back on June 15 as that player. Similarly, in ’80, the Yankees traded catcher Brad Gulden to the Mariners, and Gulden was returned to New York a year later. Pitcher Dickie Noles was sent from the Cubs to the Tigers for just 33 days in ’87 before being returned to Chicago. The Tigers were again involved in a similar swap in 2005, when they received infielder John MacDonald from the Blue Jays in July, only to give him back to Toronto that November.

Trading personal lives

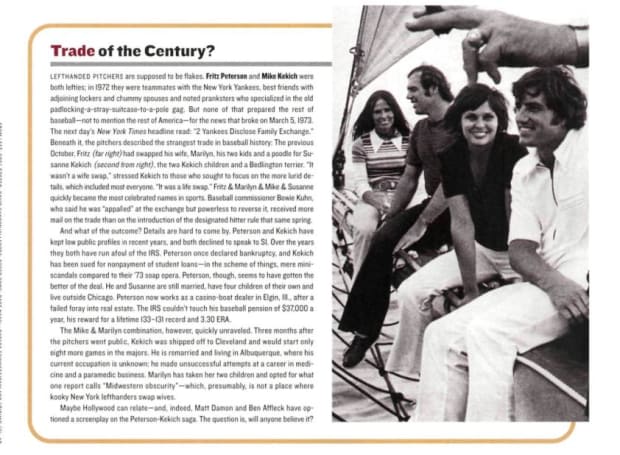

It wasn’t exactly a trade sanctioned by any baseball league, but the transaction between Yankees players Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich remains one of the weirdest of all time. In 1972, the two Yankees pitchers traded lives, switching their houses, wives, kids, and even their dogs.

They announced the swap during ’73 spring training, in separate press conferences. “Don’t say this was wife-swapping, because it wasn’t. We didn’t swap wives, we swapped lives,” Kekich said.

via SI Vault

MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn spoke against the arrangement, saying “I deplore what happened and am appalled at its effect on young people.” Kekich was traded to Cleveland in June of that year, and he ultimately split with Peterson’s former wife. Peterson, a one-time All-Star in ’70, was also traded to Cleveland a season later. Peterson and the former Susanne Kekich are still married to this day.