When Ron DeSantis took his first steps into the professional world in 2001, he probably didn’t forsee himself on a path leading to a showdown with a hotel magnate who in three years would go on to host The Apprentice on network television.

But, in many ways, Mr DeSantis’s role in the national spotlight seemed almost predetermined, even all those years ago when he was little more than a junior Navy officer bound for his first assignment. The Yale-educated DeSantis, 44, now finds himself the face of a surging faction in the Republican Party that seems as eager to move on from its party’s past as it is to pick fights with America’s new cultural norms — a direct evolution of the previous iteration of the GOP which saw its credibility hemmhorrage due to the failure of the Bush administration to prove any of the claims that led the US into war with Iraq.

Born to Ronald and Karen DeSantis in 1978, the man who would become Florida’s current governor was one of the first Republican leaders to emerge in Washington with his politics primarily tempered by the War on Terror. A graduate of Yale and later Harvard’s law school, Mr DeSantis was commissioned into the Navy three years after the attack on 9/11 at a time when America was beginning to reckon with the fact that its investment of military force in the Middle East was not to be a short-lived excursion.

The young DeSantis was immediately thrust right into the middle of that reality: two short years after his commissioning, he would find himself assigned to legal observational duties at America’s infamous Guantanamo Bay military prison, where both battle-hardened al-Qaeda fighters as well as those with no proven connections to terror groups endured some of the US’s most extreme methods of interrogation and incarceration.

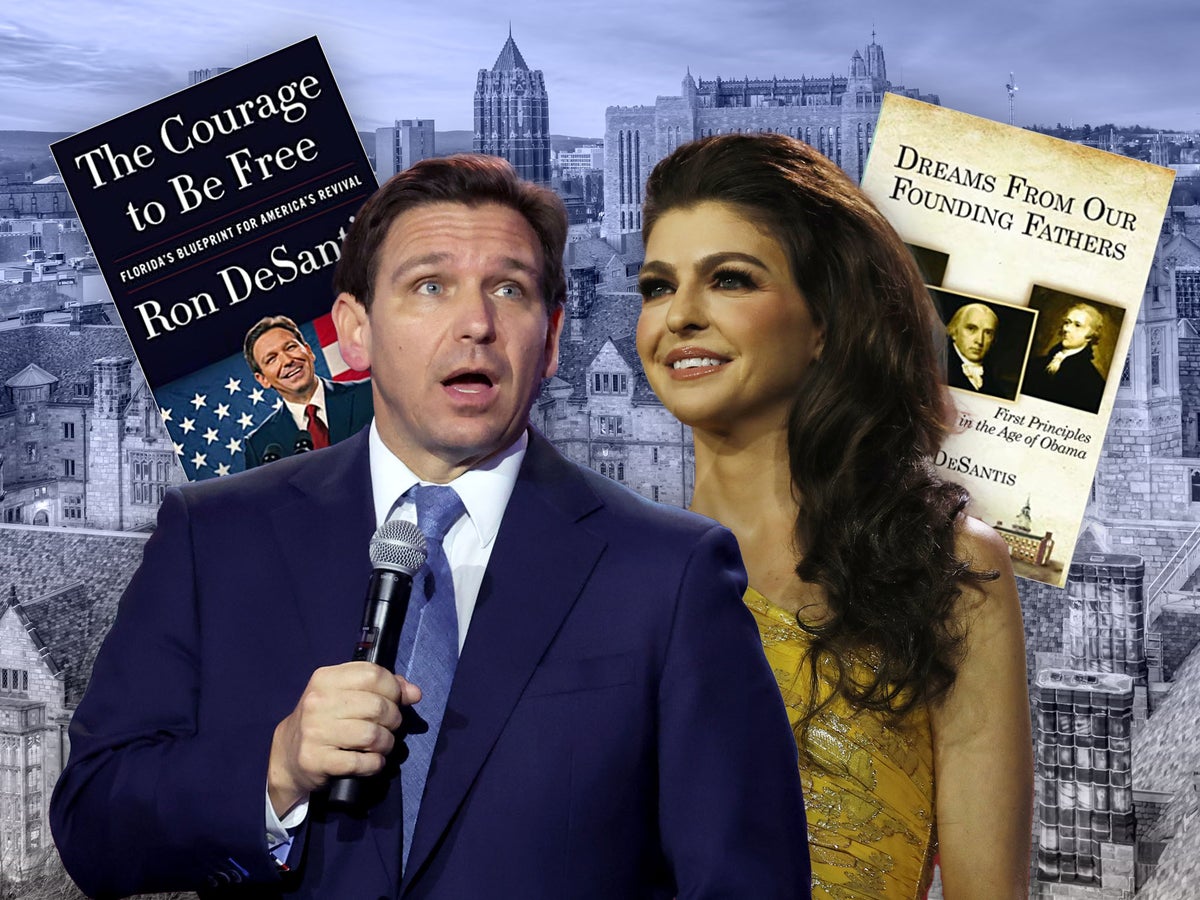

Mr DeSantis writes of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in his memoir, The Courage to be Free: “One recruiter told me that the assumption was that the Iraq campaign would be over relatively quickly, and that there would be a need for military [attorneys] to lead prosecutions in military commissions of incarcerated terrorists at Guantanamo Bay.”

“That turned out not to be what happened, but it seemed plausible at the time,” he lamented.

His duties at the prison remain shrouded in the secrecy that has hung over that facility for decades; most recently, it was the source of a dispute between the governor and a former detainee at the prison who told The Independent Mr DeSantis was present for episodes where prison officials conducted force-feedings of prisoners, a practice the United Nations condemns. The governor has denied this claim.

Mr DeSantis’s time at Guantanamo was just the beginning of his contribution to America’s two decades of war in the Middle East. Despite not holding a rank that would ever mean he would see combat, Mr DeSantis was part of the 2007 troop surge in Iraq that saw the country stabilised to an extent for a number of years, at least until the rise of the Islamic State. He would serve as a legal adviser to a commander in Fallujah, one of the sites of the fiercest combat between US-aligned forces and insurgent militia groups, some of which were armed and supported by Iran.

Finally discharged in 2010, Mr DeSantis’s path to elected office seemed almost expected; a Yale- and Harvard-trained attorney with crediblity stemming from his military service reads like a dream candidate on paper for either party, and for a GOP still reeling from a bruising defeat to Barack Obama two years earlier the would-be Congressman Ron DeSantis was a no-brainer. He easily won a seven-way primary for a congressional seat representing the state’s 6th district, earning a more than 15 per cent margin of victory over his closest rival, and joined the House of Representatives as part of the GOP’s midterm coup of both chambers of Congress that year.

The Floridian freshman wasted no time establishing a name for himself in the lower chamber. He was a founding member of the far-right Freedom Caucus, a group that saw the height of its relevance during the Obama years by earning labels of obstructionists from Democrats and true believers from their party base. He struck hard-right stances on issues like immigration reform, healthcare and gun control, becoming a noted foe of liberal organisations backing such causes and giving voters a slight preview of the culture warrior who would later emerge after his election to the governor’s mansion.

His service continued through the Obama years into the first year of Donald Trump’s presidency; during that short 12 months, he distinguished himself as a GOP loyalist once again by backing legislation that would have defunded the now-defunct Justice Department investigation into the Trump campaign and Russia headed up by Robert Mueller.

As 2018 rolled around, Florida’s Republican Party faced a question: would the state continue its slide to the right, a process begun under the incumbent Rick Scott, who sought a Senate seat as his second term expired? Or would Florida Democrats prove that the Sunshine State was still a purple battleground, despite their failures to make more meaningful inroads with the state’s Latino population?

A hard-fought campaign ended in the former coming to pass, and in a nightmare scenario for Florida’s Democratic Party. Mr DeSantis and the Florida GOP would turn a 0.4 per cent margin of victory over Andrew Gillum, at the time one of the Democratic Party’s most popular rising stars, into a mandate for passing into law a right-wing agenda that would go on to be condemned by national anti-racist and LGBT+ rights groups as an attempt to shove the state back into America’s racist past. Mr Gillum, meanwhile, personally and professionally imploded; two years after his defeat, he would find himself at the centre of a scandal involving crystal meth and photos of the former gubernatorial candidate unconscious, in a pool of vomit, on a hotel room bathroom floor.

Having successfully defeated a popular Black Democrat who appealed widely to Florida’s diverse left-leaning voter base and sea of independent voters, the governor had little trouble seeing off a challenge from an ageing, white centrist Democrat (who was previously a Republican), Charlie Crist, in 2022. Now, Florida is a solidly red state, with the GOP making further gains under the governor in an otherwise bad year for their party nationally in 2022.

In total, it seemed like Mr DeSantis had compiled a resume that checked every box for GOP voters, and more crucially the party’s establishment too. Veteran conservative political operative Rick Wilson said that Mr DeSantis’s CV looked appealing to many before they actually came in to contact with the man himself: “When you looked at it [from] five miles away, he was a swing-state governor, very successful in the legislature.”

All of this brings us to 2024, where Mr DeSantis is widely viewed to be the only (currently) credible challenger to Donald Trump in a Republican primary contest. And while the two men do not differ significantly on policy - if anything, Mr DeSantis has leaned into the same pool of far-right conservatives that Mr Trump relied on in 2016 - other differences between the two cannot be ignored. The governor is more than 30 years Mr Trump’s junior, married with three young children and therefore has set his likely opponent up for the very contest that Republicans have tried to provoke on the left with questions about Joe Biden’s age. He also has a record of recent electoral success, setting himself up for a unique battle with Mr Trump over electoral fraud and the ability to beat Democrats in general election contests.

But there remains one question: will any of this be enough? The governor is currently sinking in the polls, unable to form an effective response to the onslaught of attacks coming his way from the former president’s team. In one poll from The Wall Street Journal, the former president has flipped a 14-point deficit recorded in December to a 13-point lead. At present, his campaign for the presidency looks to be going the way of Mr Trump’s main 2016 rivals, Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio - or worse, like that of the last Florida governor to enter national politics, “low-energy” Jeb Bush.

There are also concerns that Mr DeSantis’s efforts to ingratiate himself with a Trump-aligned GOP base in Florida will hurt him in front of a national audience. His war with Disney, once the source of headlines that energised conservatives furious with the company’s acceptance of LGBT Americans, has evolved into a lengthy and costly legal fight that just recently resulted in the company cancelling a major investment in downtown Orlando.

“His fight with Disney, which at first looked like a principal fight against wokeism, now looks like an Ahab-style vendetta,” said Mr Wilson.

The problems were most clearly evident after Mr DeSantis’s DC swing earlier this year. Following his visit to drum up support for his own run, several GOP lawmakers including Florida’s Byron Donalds came out in support of Mr Trump’s 2024 bid.

Patrick Murray, director of Monmouth University’s polling institute, theorised that the reasons for Mr DeSantis’s popularity could also be his greatest hurdle going into 2024: Voters see him as the natural devolution of Trumpism to the states, rather than the movement’s evolution on the national stage.

“[T]o the extent that GOP voters have been tracking DeSantis, it’s more as a continuation of Trumpism, rather than a desire to move away from Trump,” said Murray.

“So the question is, who is the stronger candidate? DeSantis’s appeal was to be seen as the strongest challenger to Biden, whether you are a Republican who likes Trump or not,” he continued. “Ironically, the more Trump comes under legal fire, the stronger his supporters think he is as a candidate. This leaves less room for DeSantis, and to the extent he has been in the news recently, it has not made him look particularly effective.”

Mr Wilson, a native Floridian, drew another comparison in an interview. Ron DeSantis, to him, is the GOP’s Hillary Clinton: the candidate who looks over-qualified for the job on paper but in-person comes off as awkward, unconvincing, even manufactured.

“There's a lot of similarity right now. If you look at it, between Ron DeSantis this year, and Hillary Clinton in 2016,” explained Mr Wilson.

The Democratic Party establishment in 2016, he continued, “wanted Hillary [to win]. She was safe, transactional, had all the coding of the meritocracy. Brilliant lawyer, all those things. It seemed great on paper.”

“There are an awful lot of similarities, the weird laugh, the discomfort with people in crowded, chaotic, non-planned environments. That just all adds up to somebody in my head that, again, the politics may be different, but the performance of both of them is strikingly low.”

His interactions with the media have fuelled those critiques. Frequent questions about his poll numbers have led to unpolished reactions from the governor, who in some cases has appeared to be flustered and unable to respond.

As the primary debates begin this year, Mr DeSantis’s future in the Republican Party is uncertain. Worse for him and his backers in the Republican Party establishment, it may come down less to a decades-long pedigree carefully crafted through the beginning of the 21st century, and more to his ability to prove that he has the one quality which GOP voters really want to see: toughness, and the ability to brawl with his enemies in the Trumpian way perfected by the man he hopes to defeat.

It’s for that very reason that Mr Wilson, who heads up the anti-Trump conservative Lincoln Project, predicts that Mr DeSantis will ultimately fail in his bid to break the former president’s hold on the GOP.

“I think we've learned over time that there is no substitute for Trump among the Trump base,” he reckoned. “Why would you buy a diet Trump when you can have the full-fat all-the-caffeine, all-the-sugar of original Trump?”