Since the recent US presidential debate, Donald Trump and his running mate JD Vance have doubled down on claims that Haitian immigrants are causing crime and disorder in Springfield, Ohio.

These claims spread rapidly because of the bogus assertion that pets were being stolen and eaten. The claims fit a pattern of assertions by Republicans – particularly around election time – about immigrant-fuelled crime. Trump also repeated false claims that the town of Aurora in Colorado has been taken over by Venezuelan gangs. In 2016, Trump made similar claims about El Salvadoran gangs on Long Island.

Although false, these claims play upon the increased number of Haitians and others seeking asylum in the US in recent years. Haiti has faced extraordinary instability since the 2021 assassination of president Jovenel Moïse. Gangs have taken control of large areas of Port-au-Prince, and increasingly of rural areas well beyond their usual turf.

But the unfounded claims also play into a long history of hostility towards Haiti, and especially Haitian immigration – despite the profound part the US and others have played in creating the conditions driving Haitians to seek asylum.

Many of the reasons driving Haitians to leave can be traced back to debt forced upon Haiti by the US and France. Major General Smedley Butler, who participated in the 19-year US occupation of Haiti between 1915 and 1934, later called himself a “racketeer for capitalism.”

In 2022, the New York Times estimated Haiti paid the equivalent of about US$115 billion to France in reparations for the Haitian Revolution – about eight times the size of its economy in 2020. Without that debt, a team of international scholars estimates the country’s per capita income in 2018 could have been almost six times as large.

The world’s first Black republic

Prior to independence, Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) was one of the most lucrative European colonies in the world. African slaves worked on French plantations to produce sugar, coffee and other crops. A slave revolt broke out in 1791, coalescing around the leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture, a freed slave.

The revolt drew the interest of other colonial powers, and over 12 bitterly violent years, L’Ouverture and the revolutionaries secured the abolition of slavery by France, aligned with and then later repulsed Spain, fought off Great Britain, and defeated Napoleon Bonaparte’s army, sent to reconquer the colony. On the first day of 1804, Haiti became the world’s first independent Black republic.

Despite occurring at a similar time and appealing to similar political values, the Haitian Revolution receives far less attention than the American or French Revolutions. Haitian-American historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes that a revolution led by Black slaves was “unthinkable” – both at the time and for later generations.

France and the US incorporated revolutionary ideals into their national identities, but punished Haiti for its revolution. In 1825, French warships returned to menace Haiti. Their mission was to extort Haiti into purchasing its independence by paying reparations to French slaveowners for the revolution.

The agreed debt was 150 million francs, to be paid in annual instalments of 30 million francs. Haiti had to take a loan from a French bank to pay back the very first instalment, creating a “double debt.” Gunboats returned whenever it seemed Haiti might miss a payment.

Two years earlier, the US announced the Monroe Doctrine, declaring the Americas an independent region. The US would view European efforts to “control the destiny” of independent countries of the Americas as an act of hostility. But the US took no action when French ships approached Haiti and imposed their debt.

Indeed, Haiti’s independence troubled slaveowners in the US (including Thomas Jefferson), who feared it might provide a template for further slave revolts. The US did not recognise Haiti as an independent state until 1862, during its own war to end slavery.

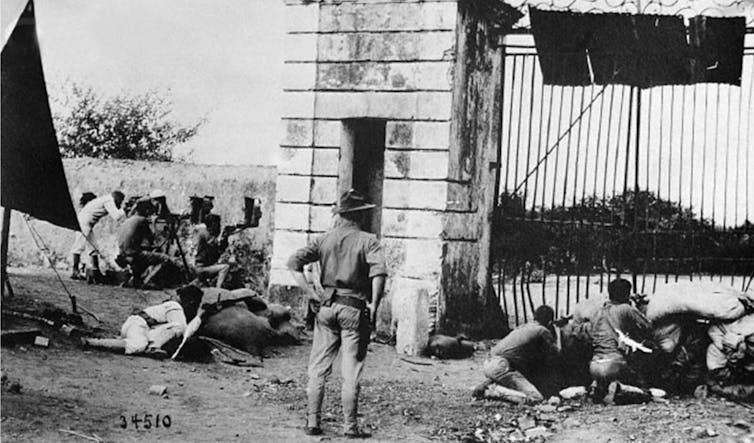

The 20th century saw decisive enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, and with it, direct US intervention in Haiti’s affairs. With political instability in Haiti, Wall Street lobbied for a more aggressive approach to securing US business interests. In 1914, the US sent its own gunboat to Haiti. US Marines removed half a million dollars in gold from Haiti’s national bank.

The following year, the US military returned, occupying the country for 19 years. As with US interventions in Cuba and the Philippines, this was cast as a civilising mission, and the local people as helpless savages.

At the same time, US banks took over where French banks left off, forcing debt upon the country. Haiti paid down its original reparation debt to France by 1888. It didn’t pay off its debt to US banks until 1947.

Democracy and detention

Following the occupation, Haiti suffered through years of political upheaval punctuated by crushing dictatorship. Self-declared “president for life,” Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled for 14 years, backed by the terror of his personal militia, the Tonton Macoutes, and the blind eye of the US, who saw him as ally in the fight against socialism. Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier ruled for another 15 years after his father’s death.

In 1991, Haiti held what are often described as the first genuinely democratic elections in the country. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a vocal critic and sometimes target of the Duvalier regime, won convincingly. Aristide implemented reforms, including bringing the military back under civilian control. Eight months into his presidency, he was overthrown in a coup.

In the years following the coup, Aristide’s supporters were terrorised by a death squad, calling itself the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti. The leader of this group, along with other military figures involved in the coup, were funded by and received training from the CIA.

Thousands of Aristide’s followers fled the coup and subsequent persecution. About 20,000 Haitians were intercepted at sea by the US coast guard, and brought to the naval base at Guantánamo Bay. The site was chosen, in part, because it was not formally US soil and thus afforded those detained no grounds for asylum in the US.

In the same period, thousands of Cubans fled the “Special Period” crisis, and were detained alongside Haitians at Guantánamo Bay. Most of these Cubans were granted asylum in the US. Most of the Haitians, by contrast, were denied asylum and sent back to the persecution they had fled.

Haitians were denied entry, in part, because of the close relationship between the US and the military in Haiti. By contrast, the US was ever-eager to paint Cuba as a totalitarian regime, and thus Cuban immigrants as genuine refugees.

The antipathy towards Haitians ran deeper still. With the emergence of the HIV crisis in the 90s, four particular at-risk categories were identified by the Center for Disease Control: homosexuals, haemophiliacs, heroin users and Haitians.

The fear of contagion spreading from Haiti to the US returned in a new form. Indeed, some 300 Haitians who were found to have genuine asylum cases were still barred from entry to the US, once they tested positive for HIV.

The struggle for freedom

The earliest Haitian immigrants in the US were white slaveowners, some of whom brought their slaves as they fled the Haitian Revolution. This is not, however, the image of Haitian immigration that Trump and Vance are trying to whip up before the November election. Rather, they are tapping into a longstanding association between poverty, violence and the free movement of Black people from Haiti.

The current hostility towards Haiti and Haitian immigration is propagated by the Republican party. But it is by no means an exclusively partisan issue.

Bill Clinton, a Democrat, feared an “alien invasion” from Haiti and ultimately preferred the return of Aristide to power over the continued arrival of Haitian asylum seekers. President Biden also favoured the removal of Haitians back to Haiti, in some cases forcibly returning children who had never lived in Haiti.

But the current political crisis in Haiti is only deepened by the fact Haitians have good reason to suspect outside interventions. Even the gangs that terrorise parts of the country know how to tap into the idea that, after over 200 years, Haiti is still struggling for its freedom.

Philip Johnson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.