Rachel Reeves, the UK chancellor of the exchequer, has been making cost-cutting announcements ahead of a crunch October budget to deal with what she says is a black hole in the country’s finances. Along with scrapping winter fuel payments, a planned cap on social care and various road and infrastructure projects, she has announced that the the Tories’ £1.3 billion investment plans for artificial intelligence (AI) will not be going ahead.

This comprised £800 million for a new supercomputer to be based at the University of Edinburgh and an additional £500 million in computing power for AI research. The supercomputer, known as an exascale, would have been the first of its kind in the UK. It would have been 50 times faster than any existing machine, performing one billion billion calculations per second and supporting researchers across the country.

When the investment was announced in 2023, Michelle Donelan, the former tech secretary, had said this was necessary for the “UK to remain a global leader in scientific discovery and technological innovation”. The best hope for UK researchers now will be to make use of the exascale computers that have already been built in Germany and France.

While the EU is clearly trying to keep pace with US and Chinese computing power, the same cannot be said of the UK. The UK’s leading computer, ARCHER2, also housed at the University of Edinburgh, is only 49th most powerful in the world, below equivalents not only in France and Germany but also the likes of Spain, Italy, Sweden and Finland.

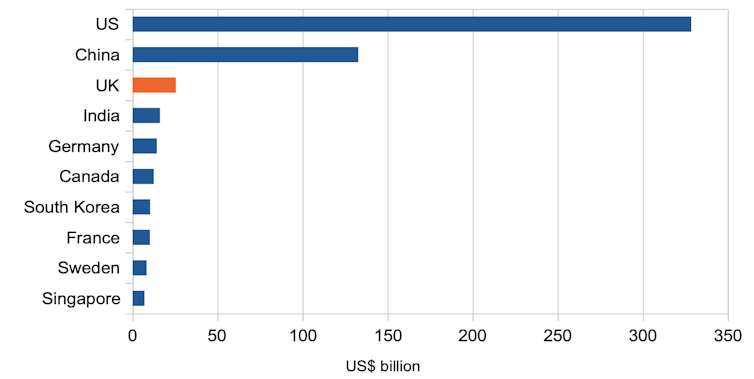

When you look at the tech investment stats more broadly, it might be tempting to conclude there’s not too much to worry about. The UK attracts more foreign investment into tech than anywhere in Europe besides France, and the third-largest investment funding specifically into AI in the world after the US and China. Yet most of the UK’s tech investment is in things such as online gambling and various other services, not really at the cutting edge.

AI investment 2019-23

As for AI, much of the investment refers to businesses upgrading their ability to use these technologies rather than creating the infrastructure to take the nation forward. The UK only has 1.3% of global computing capacity, and is evidently falling behind other advanced economies: Germany and France are at 4.5% and 3.6% respectively. Without investment to improve UK computing power, how much longer will it remain an attractive location for AI investment?

The wider problem

The UK’s digital infrastructure is also lagging behind in many other respects. Its average broadband speed is 2.4 times slower than the United States and 2.7 times slower than in Singapore. In terms of fixed broadband, meaning broadband delivered by cable, the UK’s average speeds are below Uruguay and Slovenia.

State of the art fibre-optic broadband is only available to around 60% of locations, way below the European average, while the UK’s 5G connectivity is toward the bottom of the table. The UK’s average mobile download speed is 118 megabits per second, compared to Bulgaria’s 288Mbps.

This is all symptomatic of a wider trend of failed investment and government hesitation. In 2019 the UK was a global leader in 5G deployment, but got delayed by COVID, supply issues and attacks on construction sites by conspiracy theorists who believed that 5G masts were playing a role in the pandemic.

Added to this was the government’s rapid ban on Huawei, which mandated that the Chinese company’s technology be removed from the UK’s 5G public networks.

This delayed the completion of 5G rollout by around three years and added costs to the tune of around £7 billion – enough for nearly nine exascale computers. I don’t want to argue that it was unwise to ban Huawei. But doing so just six months after the company’s 5G involvement had been approved was completely unexpected. Like the supercomputer decision and the recent political volatility in the UK, this discourages private sector investment.

The UK economy also lacks digital skills. For instance, 18% of adults lack the essential digital skills needed for the workplace, while 46% of businesses struggle to recruit people with “hard data skills” such as data analysis and computer programming. The government estimated in 2022 that the digital skills gap costs the UK economy as much as £63 billion a year in potential GDP, which could rise to £120 billion by 2030.

Now, the rise of AI is rapidly changing the playing field. Keir Starmer, the prime minister has said that the Edinburgh exascale made “little strategic sense”, but I’m afraid I can’t agree.

Its cancellation, which comes after the University of Edinburgh had spent £31 million on new facilities for the machine, has rightly been called science’s HS2 moment. It demonstrates to investors that UK tech strategy is still vulnerable to government whim.

In the US, China and EU, next-generation supercomputers are facilitating the breakthroughs of the future. It means that groundbreaking discoveries that could future-proof the UK economy may now be made elsewhere, forcing the UK to purchase and license them instead.

The UK should borrow to invest in the economy of tomorrow, and demonstrate a long-term vision for funding which survives changes of government. At such a critical time in the development of AI, Rachel Reeves’ upcoming budget might be the last realistic chance to change course.

She should either reverse the exascale decision or announce new digital infrastructure of equivalent ambition. This needs to be part of a proper AI industrial strategy that includes heavy investment in national training and upskilling, while investing in the connectivity that will allow digital innovations to thrive.

Without this kind of commitment, investment into AI and other leading tech will almost certainly start heading elsewhere. The chancellor promises tough decisions in the coming budget. It will certainly be tough for her to commit to this kind of investment at the scale that is needed. Nonetheless, she should.

Richard Whittle receives research funding from numerous sources including Research England, the ESRC, and UKRI.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.