Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

A tweet that recently went viral asked one simple question: “What’s your pet theory about the causes of birth rate decline?”

The answers that came back varied wildly.

“People everywhere have higher expectations for everything: their spouse, quality of life for kids, etc. it can really all be traced back to that.”

“Birth control + cost of living.”

“People are too stressed, overworked, and more focused on careers and personal goals.”

And, hilariously: “Men are mean and everything is too expensive.”

The immutable fact that people are having fewer babies is a subject that’s been steadily gaining attention. In the UK, the birth rate has been noticeably on the wane since 2010, with the average birth rate in England and Wales sinking to 1.49 children per woman in 2022 – the lowest rate on record. It’s well below the so-called “replacement rate” of 2.1 children per woman, the number of babies needed in developed countries to maintain a steady population.

But it’s not an issue peculiar to the UK; birth rates are falling the world over, other than in Sub-Saharan Africa. Two-thirds of the world’s countries now have childbirth rates below the replacement rate. The issue is particularly pronounced in Southeast Asian countries: Taiwan, China, Thailand and Japan are all towards the bottom of the fertility table.

There are two broad trends at work here, according to Prof Sarah Harper CBE, a professor of gerontology at the University of Oxford. The first is an extension of something that started in Europe 250 years ago: “When you improve women’s education and healthcare, it reduces the number of children she’ll have. That’s a very good thing – more women being healthy, educated and having access to family planning.”

The other trend has happened more dramatically over the last 30 years, and is particularly notable in Asia and Latin America. This second fall in fertility, where we’re seeing birth rates below 1.5 children, “seems to be driven by different dynamics”, says Prof Harper. “Responses from young women are the same in Southeast Asia as in Europe: yes, women are saying there are economic issues, insecure jobs or challenges with affordable housing. But they’re also saying, ‘I’m educated and I understand that if I have a child that will change my lifestyle. I want to consider when I have a child’.” They might decide to stay child-free, to delay having their first child, or to only have one.

South Korea, whose rate was already the world’s lowest, plunged again last year to a record nadir of 0.72. On the one hand, the country’s twenty and thirty-somethings seem more interested in spending what disposable income they have on fashion, restaurants and travel: “They are status hunting. Their high spending habits show young people are working on their own emblems of success online rather than focusing on the impossible goals of settling down and have children,” Jung Jae-hoon, a sociology professor at Seoul Women’s University, told Reuters.

On the other, a growing gap between the genders has prompted a fringe movement called 4B, in which women swear off heterosexual dating, sex, marriage and childbirth in response to the country’s deep-rooted misogyny. South Korea’s incidence of intimate-partner violence was found to be 41.5 per cent in a 2016 survey, compared to a global average of 30 per cent, and its gender pay gap is the largest in the developed world.

Women are becoming more vocal about what they need and that it has to be egalitarian, it has to be equal— Professor Pragya Agarwal

These circumstances are clearly very particular to South Korea, but the reality they speak to perhaps resonates further afield. It’s a world in which a kind of Peter Pan syndrome sets in and adults appease themselves with smaller luxuries as they feel powerless to afford life’s big milestones like houses, weddings and kids; one in which heterosexual, cis-gender men and women feel increasingly divided when it comes to ideology and emotional maturity.

When a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, Daniel Cox, surveyed more than 5,000 people in the US about dating and relationships, nearly half of college-educated women said they were single because they struggled to find someone who met their expectations. Cox said his interviews with male participants were “dispiriting”; he found that the men were “limited in their ability and willingness to be fully emotionally present and available”.

Yale anthropologist Marcia Inhorn also concluded in her book Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs that one of the main reasons educated women freeze their eggs is because they’re unable to find a suitable male partner. She charted the “frustration, hurt and disappointment” of women who were “almost without exception … ‘trying hard’ to find a loving partner” but came up short.

I see echoes of this suitability discrepancy when I think of my own status as a child-free 37-year-old woman. Not having kids feels less of a choice, more of an inevitability resulting from the dearth of potential partners prepared to put down roots and get serious about the responsibilities that come with a relationship. And, while there’s much I’d compromise on, I know I would only want children under a very specific set of circumstances: with a committed partner who I was certain would step up and share the load, 50/50, when it came to parenthood.

“Women are becoming more vocal about what they need and that it has to be egalitarian, it has to be equal,” agrees Prof Pragya Agarwal, author of (M)otherhood: On the choices of being a woman. “That it’s not just the woman’s responsibility to look after the children or to do certain things at home. There’s a wider conversation happening around emotional and mental labour that women have to perform. Many people who have held a higher position in the hierarchy, like men, haven’t acknowledged this notion that there was previously inequality and that they now need to step up. That is creating challenges in heterosexual relationships, where there is a gap between women’s and men’s expectations.”

What this means in practice is that, despite the fact that more women are actively opting out of having kids than in previous decades (and facing less stigma for doing so), some aren’t having them due to circumstance rather than choice.

“It’s fantastic that women are able to say, ‘this is the kind of life I want, I’m not prepared to compromise on that’,” she adds. “But some women are being forced to make this choice even when they want children, because the alternative is that they just take on all the burden, or they become mothers and then don’t progress in their careers. They don’t have the support in the workplace or at home, and they’re exhausted all the time: financially, emotionally, physically.”

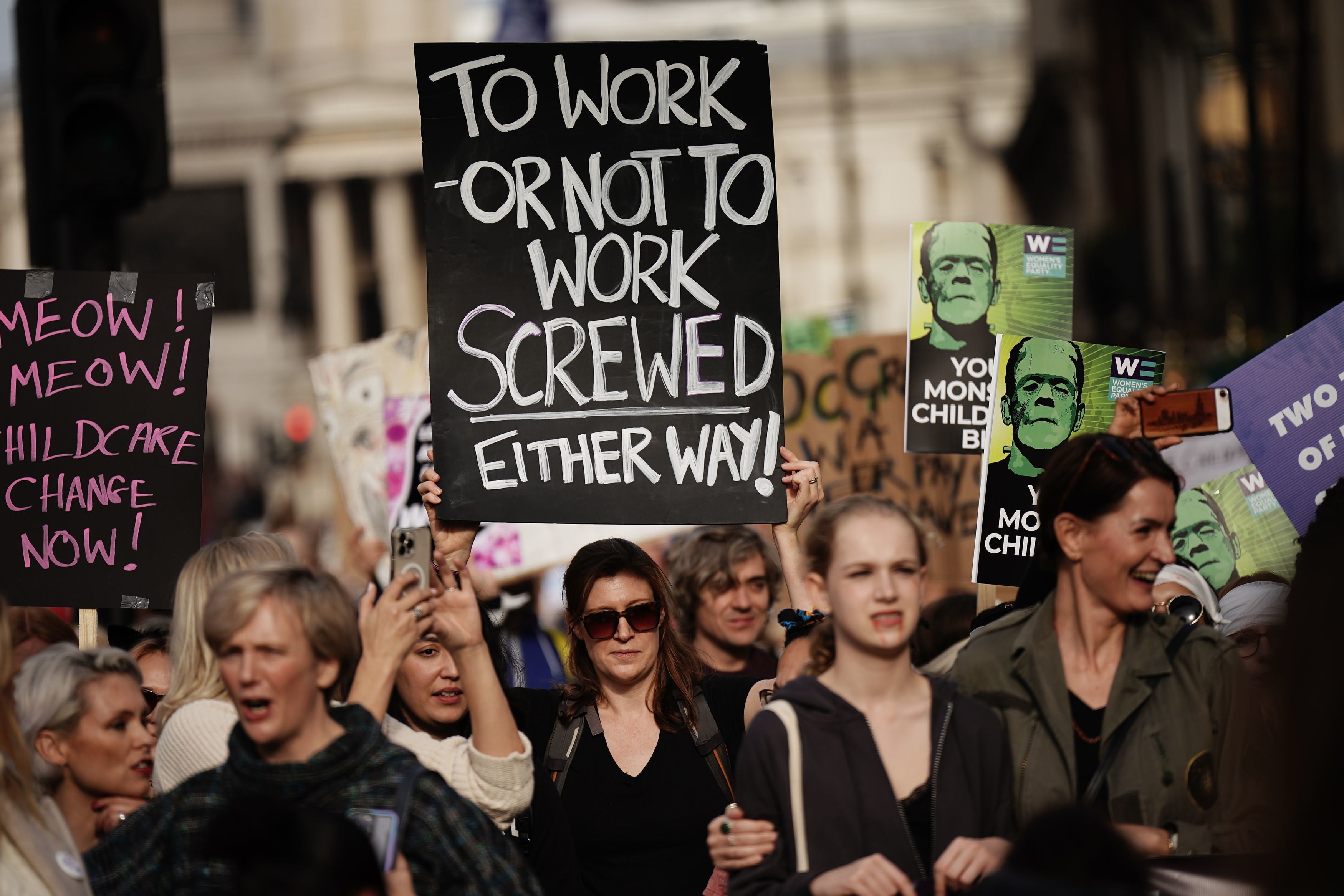

One way in which societal infrastructure isn’t in place to encourage women to willingly procreate is the often abysmal maternity provision and the exorbitant cost of childcare. In the UK, the latter rose by nearly 6 per cent last year, taking the average price of a full-time nursery place for a toddler under two to £14,836 per year – and making it the third-most expensive country for childcare in the world, based on a couple earning the average wage, according to data from the OECD. Some 63 per cent of parents have delayed having another child or decided against having more due to the cost of childcare, according to one 2023 survey of 1,000 parents with children under four.

Then there’s climate concern – the very real fear that potential parents are bringing children into a world in which the future looks increasingly uncertain, bordering on dire. A piece of research from Nottingham University in 2022 found that 48 per cent of Brits agreed that anxiety about climate change had to some extent made them think they should not have, or now regretted having, children.

There is no level of policy intervention that is likely to encourage childbearing— Vegard Skirbekk

But according to one school of thought, the problem is bigger than heightened expectations of equality, men’s “lost boys” affliction, financial barriers and worry about the planet being on fire. The problem, in fact, could encompass all of this and more, attributable to a kind of global malaise. Inequality and social isolation have led to an “epidemic of despair” – and that is what’s driving down fertility rates worldwide, posits a 2024 paper by Penn neuroscientists Michael Platt and Peter Sterling.

The cause of this “catastrophic” rise in anxiety, depression and related diseases? The increase in our lives becoming more digital and the shift from real-world to online interactions, it claimed, hypothesising that this acute sense of loneliness is contributing to more physical and mental ailments, particularly in high-income countries, and dampening the most basic of human drives: procreation.

This perhaps explains why pro-natal government schemes to financially incentivise having kids are doing little to reverse the trend. “Essentially, there is no level of policy intervention that is likely to encourage childbearing, that is likely to affect fertility rates during the long term,” Vegard Skirbekk, a Norwegian population economist and author of the book Decline and Prosper!: Changing Global Birth Rates and the Advantages of Fewer Children, tells me. “Many countries have tried and failed.”

And, though there might be issues that come with an ageing population, it’s also inevitable. “The UN said many years ago – and any demographer would agree with this – that ageing will occur no matter what,” says Skirbekk. “We are living longer.” This means a fairly rapid increase in the number of countries where more than half of the population is aged over 50. Societal adaptations will have to be made, but technological changes and automation could help fill gaps in an older workforce.

We also need to consider immigration as a tool – “There are huge numbers of young people elsewhere with skills and talents,” says Prof Harper. She also recommends looking at opportunities within our own local population. “If women are having fewer children, they can play a greater role in the workforce, and if we’re healthier in general, we can work for longer. It’s a challenge but I don’t necessarily see it as a problem.”

In fact, the widespread assumption that a dip in fertility is inherently bad could be misleading. Skirbekk agrees: “There is no way around it, and there are many positive aspects that people tend to downplay.”

Carbon emissions, for one. On a fundamental level, fewer people equals a smaller footprint. “Personally, I think it’s a good thing,” Prof Harper says of lowering birth rates. “We’re a planet of eight billion people, and we’ll still likely see this increase to potentially 12 billion. We know climate change and the consumption of goods and natural resources is going to only going to increase; the pressure is only going to increase.” A fertility decline will, if anything, alleviate some of that pressure.

But she stresses that, if you want children, you shouldn’t let environmental guilt stop you from having them. “Just make sure your family and your household is low-consuming.”

One thing the experts all agree on is that if you want to swap “Bye Bye Baby” for “Hit Me Baby, One More Time”, we need to be better supporting those who do want to pursue parenthood. “We have to look at equality in the workplace and equality at home,” says Prof Harper. “There has to be good, affordable childcare available.”

Governments creating a panic around declining childbirth isn’t going to help anybody. But implementing policies to actually support women who want babies? That just might.