After weeks of wrenching testimony, jurors delivered a guilty verdict June 16, 2023, for the gunman who killed 11 worshippers in a Pittsburgh synagogue in 2018 – the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history. The next phase of the trial will focus on sentencing, and whether Robert Bowers should face the death penalty.

The name of the synagogue, Tree of Life, has almost become shorthand for the tragedy. Yet it highlights a symbol from the Bible that has transformed over time, coming to represent how the human and the divine relate through revelation. In Jewish Scripture and Jewish thought, the tree of life speaks to fundamental aspects of what it means to be human in the world.

In my research as a scholar of the Bible and ancient Judaism, I have been amazed at the potency of the symbol of the tree of life. Not only has the symbol itself transformed over time, but it has the power to transform communities along with it.

In the beginning

The tree of life appears in the Book of Genesis, at the very beginning of the Hebrew Bible – what many Christians call the Old Testament.

In the creation story of chapters 2 and 3, God places man in the Garden of Eden, then creates woman, Eve, from his rib. Eden is filled with “every tree that was pleasing to the sight and good for food,” as well as the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil – but God commands the man not to eat this last tree’s fruit.

Before long, however, a serpent tempts Eve and Adam to do just that. When the serpent speaks, it addresses Eve directly – and for centuries, art and stories about the Garden of Eden have portrayed her as “responsible” for succumbing to temptation.

Yet in the Hebrew text, the snake often uses verbs for the second person plural, suggesting that it is addressing Adam as well – or at least implying the benefits of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil will apply to him, too.

Biblical scholars debate the meaning of the tree’s name: what exactly do “knowledge” or “good and evil” entail? Persuaded that eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil will make them like God, however, Adam and Eve consume the fruit. Worried that the couple might eat from the tree of life as well, making them immortal, God expels Adam and Eve from the garden and places a flaming sword and angelic beings at the entrance to prevent reentry.

This transgression of the boundary between divinity and humanity begins a recurring theme in the Bible, one that famously appears in the story of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11. In this latter passage, humans build a tower and a city without conferring with God at all – both acts that, in the ancient world, defied divine prerogative.

Two trees

These two trees, especially the tree of life, have long raised questions for scholars. Though the tree of life is introduced at the same time as the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the rest of Genesis’ creation story focuses on the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The tree of life does not reappear until the end of the Eden story, when God expels Adam and Eve to prevent them from eating it.

Some scholars have argued that the two trees in Genesis emerged from two distinct traditions in the ancient Near East. The tree of life symbolism had a long history in the region. Kings from Assyria in ancient Mesopotamia and elsewhere would use a verdant tree in imagery to evoke the wonders and fertility of their domain.

The two themes associated with each tree, however – wisdom and immortality – are connected in other ancient myths. In one legend from Mesopotamia, for example, in modern-day Iraq, the first human is named Adapa.

Ea, the god who created Adapa, gives him wisdom from the start. Ea then offers the man food that would lead to immortality but tricks Adapa into refusing it. The result is that humans have some wisdom, like the gods, but are not immortal and cannot challenge the divine.

Similarly, the two trees in Genesis display how humanity is both like and unlike God. According to other texts in the Bible, such as Psalm 82, divinity is characterized by immortality and a concern for justice. Adam and Eve ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, giving humanity some sense of self-awareness, justice and, ideally, care for the poor and oppressed. Humans did not consume the tree of life, however, creating a distinction between them and the divine.

Living wisdom

In Genesis, readers are introduced to “the” tree of life, with the definite article – implying there is only one such tree.

Later in the Bible, however, “a” tree of life appears four times in the Book of Proverbs, a complex anthology that collects many sayings and gems of wisdom from the ancient world. A possible, though by no means certain, allusion also appears in the Book of Ezekiel.

Some of these passages in Proverbs use the imagery of a tree of life as a positive contrast to sickness, languishing or broken spirits.

Other verses connect knowledge and a tree of life. Proverbs 3:18, for example, instructs that wisdom “is a tree of life to those who grasp her, and whoever holds on to her is happy.”

Jewish tradition frequently pictures God’s teachings and scripture, the Torah, as the tree of life – deepening this connection between life and wisdom.

Reaching up to God

In Genesis, the tree of life is a symbol of the divide between humanity and divinity. In the Bible’s wisdom literature, however, it comes to represent how knowledge, wisdom and Torah connect God and Israel. Both meanings continued to evolve in a strain of Jewish mysticism known as Kabbalah, which has roots in the 13th century

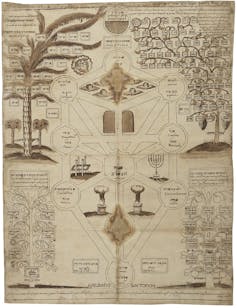

The most famous texts of Kabbalah discuss the relationship between humanity and divinity in terms of God’s attributes, such as righteousness, justice and beauty. These attributes, called “sefirot,” are often drawn as spheres, linked with branchlike lines as though they form a “tree of life” – a tree that connects human experience on Earth to an infinite God above.

Mystical tradition sees these pathways through the “sefirot” not only as a means of connecting divinity and humanity, but also as a means of repairing our broken world, where believers may feel that the divine is often absent.

According to these teachings, when people access spheres on the tree of life through mystical reflection and study, they aid in “tikkun olam,” the repair of the world.

It is no wonder, then, that the tree of life holds so much significance for Jewish communities. Like the synagogue in Pittsburgh, they can experience tragedy, even as they continue seeking ways to heal a broken world.

Samuel L. Boyd does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.