The white sails of the Sydney Opera House in Australia seemed like “an obvious canvas for an important message”, recalled David Burgess, even if scaling the building with a tin of red paint was a “bit hairy”.

It was March 2003, and Burgess along with his friend Will Saunders had been watching the build-up of troops ahead of the Iraq war. So they came up with a plan to write “NO WAR” somewhere that the world would see it.

The opera house seemed like the right place for their protest, since “most people around Sydney have some sort of connection with the building”, Saunders told Al Jazeera in an interview ahead of the iconic building’s 50th anniversary,

It is this sense of connection that lies behind “The People’s House” being chosen as the theme of official celebrations this month. Fifty years after construction was completed, it is worth looking back at how the title was earned and whether it remains true today.

“Hats, cupcakes, flower petals, [dishes drying on a rack], even a camper van,” these are just some of the ways that the Sydney Opera House’s sails have been imagined, Cristina Garduño Freeman, a senior lecturer in Architectural History at the University of New South Wales told Al Jazeera.

The affectionate nicknames are just one way that Freeman says the building has been “embraced by the public”, adding to its icon status.

But the opera house, designed by the Danish architect Jorn Utzon, has always been far more than a beautiful building.

In 1960, 13 years before construction was eventually completed, the workers who built it held one of its most memorable performances.

They had invited African-American singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson to perform at the construction site as part of his first world tour since the United States returned his passport that had been taken away because of his political beliefs. Some of the builders hung from scaffolding to get a better view of Robeson as he sang Ol’ Man River in his deep rolling baritone.

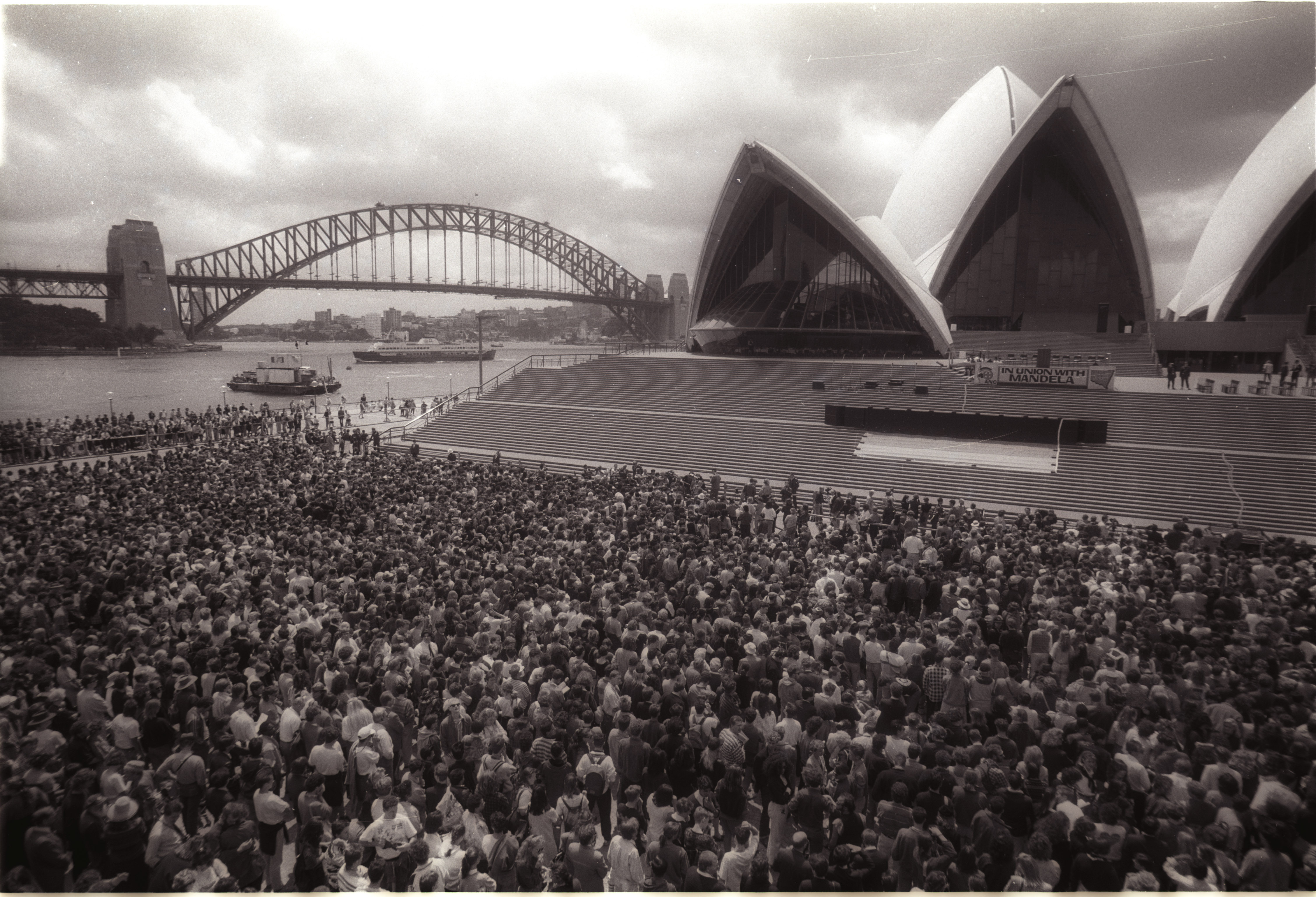

Thirty years after Robeson sang for the builders, another civil rights icon, Nelson Mandela stood on the steps of the by-then-completed opera house to address a crowd of 40,000 people.

Mandela chose Sydney as one of his first international destinations after being released from prison in part because of the support he received from the anti-apartheid movement in Australia.

Together, the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Sydney Opera House have made the shores of the Sydney harbour one of the most iconic skylines in the world.

But a controversial casino at Barangaroo now towers far above them both.

Tone Wheeler, a registered architect and president of the Australian Architecture Association, told Al Jazeera that the Barangaroo precinct was one of many examples of more commercially-based projects winning out over-ambitious architectural designs in Sydney in recent years.

Australia is building fewer public projects than it did in the past, says Wheeler, noting the growing number of art galleries, sporting facilities and social housing projects built as public-private partnerships, a trend not limited to Australia.

Such partnerships often have a closer focus on costs.

“I think architecture has become very commodified and it’s also become very conservative,” said Wheeler, who says “all the evidence” suggests an ambitious design like the Sydney Opera House would not have been built in Australia today.

And while the Sydney Opera House may be known as “the people’s house,” Sydney itself has become one of the most expensive places to live in the world.

Commercial creep

Even the opera house has not avoided the creep of commercial interests.

In 2018, Australia’s then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison welcomed a proposal to use the building to advertise a horse race, describing the opera house as the city’s “biggest billboard”.

Other recent projections include a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, a ribbon in remembrance of people killed in the catastrophic Turkey and Syria earthquakes and the colours of the Ukrainian flag.

But the speed at which images can now be projected onto the building has raised questions about what does, and does not, get reflected on its white surface.

Earlier this month, as the building was illuminated in blue and white, the colours of the Israeli flag, hundreds of people wearing the colours of the Palestinian flag gathered in the forecourt below.

The decision, reportedly made by the New South Wales state government, was questioned by Sydney’s Lord Mayor Clover Moore.

“We’re a multicultural community; we have large Muslim and Jewish communities, people from Israel, people from Palestine, we should support both communities,” she said.

Projecting images on the opera house is perhaps a much easier way to send a message than scaling its heights with a tin of red paint, but Burgess says that artists and activists have also projected their works onto its sails.

The Vivid Sydney festival of lights, which began in 2009, “really showed what could be done with that canvas”, he said.

The landmark is a centrepiece of the festival, with the sails turned into art installations and some venues taking place inside.

And the images projected on the opera house have not always had official backing, Burgess recalls.

Back in 2001, Deborah Kelly and a group of artists calling themselves boatpeople.org projected a tall ship, similar to the one on which British settlers arrived in Australia, above the words “boat people” on the side of the opera house. The protest came after then-Prime Minister John Howard refused to accept asylum seekers who had been rescued after their boat sunk off the coast of Australia, which led to the creation of Australia’s offshore detention system.

Reflecting on the day he and Saunders scaled the building to write “NO WAR,” Burgess says it was “still relevant, in the sense of bearing witness”, even if the Iraq invasion went ahead, with Australia among the countries participating. He hopes their message at least “made a few politicians think twice about committing their nations to war.”

Burgess and Saunders’s protest is now documented in an exhibit at the Australian War Memorial but, at the time, they were convicted of “malicious damage” and served weekends in prison for about nine months.

They were also ordered to pay more than $150,000 Australian dollars ($94,828) towards the costs of the workers who had to abseil down the opera house to scrub away their message. They raised the money through benefit concerts and other more old-fashioned fundraising techniques in the days before mass online fundraisers.

Burgess still enjoys visiting the opera house – he saw the band the Pixies there and has eaten meals on the foreshore overlooking the landmark.

On these visits, he sees the security fence erected after their protest has remained.

“I guess that was our contribution to the design of the Opera House”.