Plenty of bands play at being subversive, but the real indicator of how much of a threat any group poses to the Establishment is how the Establishment ultimately reacts to their provocations.

Rod Swenson, impresario for notorious punk/metal band the Plasmatics, received a unequivocal response from the Man one fateful night, in the form of gloved fists, police jackboots and billy clubs: “They beat me to a bloody mass of unconsciousness,” he says.

Formed in 1977, the Plasmatics were the twisted brainchild of two great American originals, both dedicated to the lifelong pursuit of kicking against the pricks. Rod Swenson’s issues with authority started when he was studying fine arts at Yale. “They tried to throw me out. I abandoned painting for conceptual and performance art,” says Swenson. “I believed painting was dead.”

After receiving his master’s degree, Swenson settled in Manhattan, where he created a radical, sex-themed theatre troupe in Times Square called Captain Kink’s Sex Show Theatre. “It was a place I could do things without limits, and if it was good enough, draw an audience,” he says. The show was a smash hit.

Wendy Orlean Williams, a blonde bombshell who had fled dreary upstate New York, auditioned for Captain Kink’s show and found her true calling there. And Swenson found a kindred spirit in Wendy: “She had this attitude that she’d rather be dead than part of this conformist world. She didn’t like consumerism, she didn’t like materialism. When she came upon my theatre, she was very comfortable for the first time in her life,” he recalls. “Our chemistry was just unbelievable. Whatever anyone thinks of the Plasmatics, it was what came out of that chemistry.”

Around the same time, the punk rock scene had started up at CBGB in New York’s seedy Bowery district. It was here that he and Wendy began dreaming up what would later become the Plasmatics. “It was a concept set up around Wendy Williams,” Swenson says. “She would be the centrepiece.”

The Plasmatics soon became the hottest ticket in Manhattan, reaching a level of notoriety no other CBGB band could match. Fuelled by outrageous onstage theatrics, their shows became instant sell-outs, and the buzz soon spread. The original idea was to offer an alternative to the decadent goings-on uptown: “We started out as an anti-disco movement,” Swenson says.

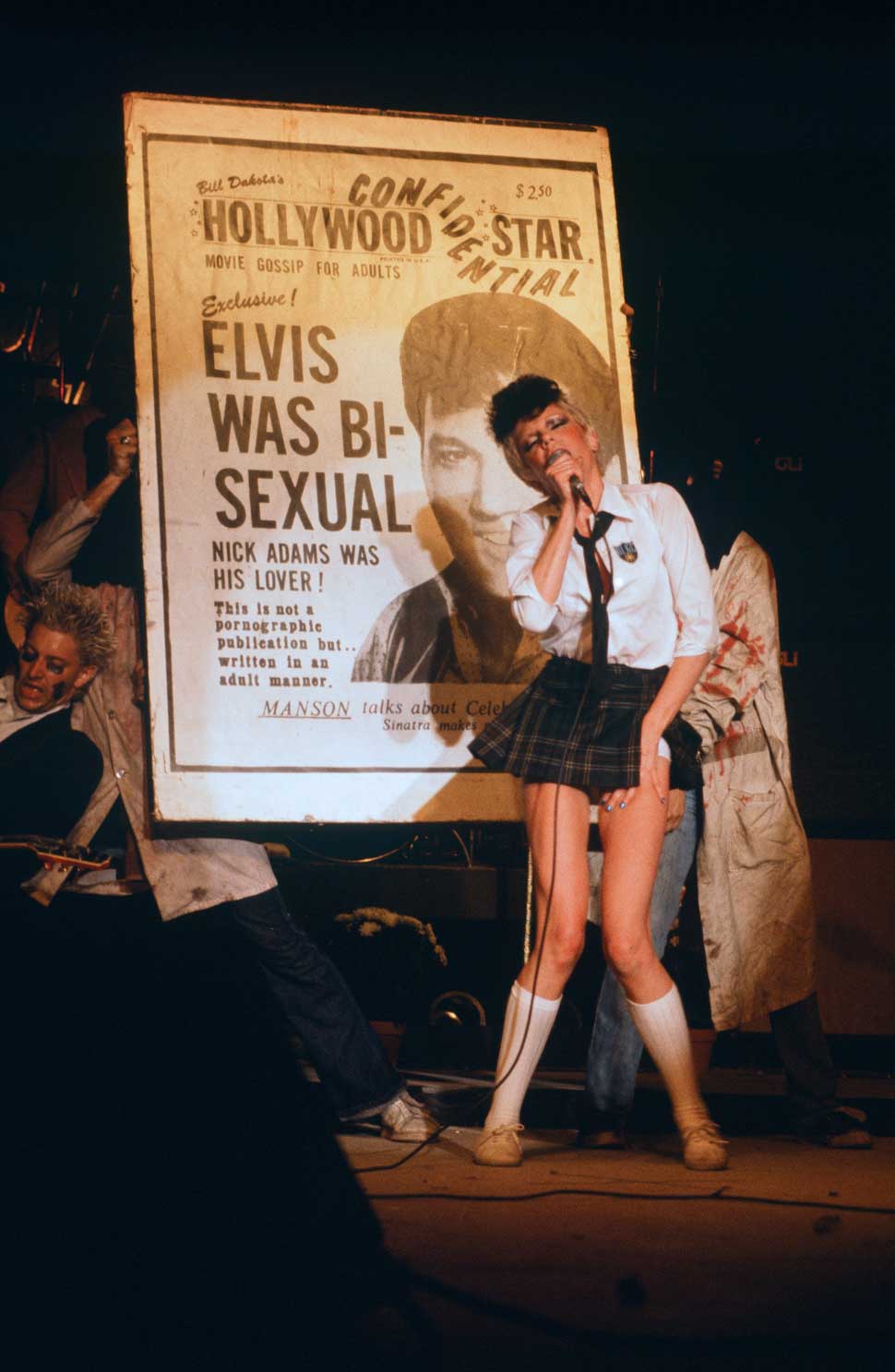

The band merged the shock rock of Alice Cooper and the Sex Pistols with big-city smut and the thrilling nihilism of Z-grade exploitation films. Wendy O Williams (as she was now known) seemed to have stepped straight out of a Russ Meyer flick, and lead guitarist Richie Stotts’s taste in stage garb – tutu, nurse’s outfits, wedding dress – clashed wildly with his nearly seven-foot frame. The Plasmatics were Middle America’s worst nightmare, in living, lurid colour: Sodom and Gomorrah on the march.

And unlike many other bands, they put the punk philosophy into action. It was one thing to deride rampant consumerism or police brutality; another thing entirely to blow up a Cadillac or police cruiser on stage. It was one thing to complain about the childishness of pop culture; it was another to smash a TV with a sledgehammer, or chainsaw a Les Paul in lieu of a guitar solo.

Despite the fact that they were the biggest live attraction in New York, they scared the major record labels shitless. At a time when anyone equipped with a skinny tie and a Rickenbacker could cop a deal, the Plasmatics were treated like they were radioactive. “They were signing these bands, and the only way they could go out on the road was with 50 grand of tour support,” Swenson says. “We were able to pay for ourselves and blow up automobiles.” After a few self-financed EPs, the Plasmatics signed to stalwart English indie label Stiff Records.

Their debut LP, New Hope For The Wretched, was supposed to have been overseen by veteran producer Jimmy Miller (Rolling Stones, Blind Faith), but due to Miller’s ongoing struggles with heroin, most of the heavy work was instead done by engineer Ed Stasium. Swenson: “[Miller] was a serious heroin addict. When he got his first advance he went over to 42nd Street and got a lot of pretty bad smack. Wes [Plasmatics guitarist Wes Beech] found him slumped over in the bathroom.” Undeterred, Swenson and Stasium took the tapes to London for the final mix.

With the record in the can, the Plasmatics began their assault on the rest of America. And as soon as the band hit the road, the media was on them like flies on jam. The press dismissed them as mere hype, saying the band were nothing but ‘porn Svengali’ Swenson’s wind-up dolls. Those accusations still get Swenson’s back up even now: “I was not a puppet-master in any sense. It’s sometimes caricatured that way as a way of marginalising Wendy, but anyone who looks at what she did would know that couldn’t be true. We were mutually inspiring.”

But whatever the critics thought, TV producers couldn’t book them fast enough – and on that medium the Plasmatics certainly didn’t disappoint. An appearance on the ABC TV late-night variety programme Fridays made them the most notorious band in America, literally overnight. Fridays had already showcased some of the biggest new wave bands of the time with little controversy, but none of those groups was given to chainsawing guitars, sledgehammering TV sets or running around nearly nude while ranting about the living dead. American conservatives – breathlessly awaiting the inauguration of Ronald Reagan the following week – found themselves confronted with a vision of hell that made Woodstock look like a church picnic.

The Plasmatics had run into trouble with the authorities before, and would do so again, but few rock bands ever faced the sort of police-state tactics Rod and Wendy would encounter in Milwaukee, two days after the Fridays slot. After a sold- out gig at the Palms nightclub, Swenson was settling up with the promoter when one of the band’s roadies told him Wendy had been arrested. As he went out to deal with the arresting officers, another roadie rushed up and told him that the police were beating Wendy up outside.

“When I got outside I saw a whole phalanx of police, and on the inside of the circle I could see half a dozen police on top of her and around her,” Swenson recalls. “One huge guy was kneeling on her back and her face was bleeding. At that point I ran through and started trying to pull them off. They dragged me between two cars and started beating the hell out of me with their nightsticks. I woke up in a pool of blood on the way to the hospital.”

Swenson later learned what had precipitated the blowout. As Wendy was being put into the police van, she told him, one cop had reached up under her shirt and started grabbing her breasts. “She turned round and belted him. So she was thrown on the ground. They could have handcuffed her at that point, but they just kept beating her,” Swenson remembers. “Even though her nose was broken and she was bleeding profusely, they threw her into the back of a paddy wagon and took her to the police station. Fortunately, as soon as they got there, a policewoman said, ‘She’s gotta go right to the hospital’.”

The Milwaukee police made no secret of the fact that the Plasmatics’ appearance on Fridays had been the cause of their wrath. “They were very angry, they were very, very vicious and they made a lot of remarks that made what they thought pretty clear. Things like, ‘Your band is made up of n**gers and queers’.”

The next day the Plasmatics had to postpone a gig in Cleveland, Ohio, because Swenson and Williams were in jail. Swenson had wanted to cancel, but Wendy insisted on going on with the show the next night. “She was not to be deterred,” he says proudly.

Their reputation preceded them, and Cleveland sent its vice squad to videotape the gig. At the end of it, Wendy passed out, possibly from effects from the previous night’s beating. The paramedics were called, but as soon as she was revived, the vice squad swooped in and arrested Wendy for indecent exposure and making obscene gestures with a sledgehammer. She was taken to the hospital and eventually let out on bail. Ultimately, she was found not guilty when the case went to trial.

To raise the money to fight the criminal charges, three benefit shows ere hosted in the name of the Plasmatics’ Legal Defence Fund at Bond’s International Casino in Times Square. They would need every penny. In Milwaukee, Swenson and Wendy were charged not only with obscenity statute violations, but also with assaulting a police officer, a felony charge that could result in serious prison time. But as the case went to trial, a photo of the cops beating Wendy surfaced, bolstering Rod and Wendy’s case of police brutality. “The cops denied the whole thing,” Swenson says. “They said I slipped on the ice.”

Swenson and Wendy were nothing if not ambitious. Although the purest expression of the Plasmatics’ aesthetic was encapsulated by their first two punk-oriented albums, punk was still esoteric for the mainstream American rock fan. If the Plasmatics were to twist the brains of the rock fans most in need of Swenson’s liberation eschatology, they would have to speak their target audience’s vernacular – heavy metal. And as Swenson says, “As soon as we heard the term ‘new wave’, we moved hard in the opposite direction.”

They tested the metal waters with their landmark Metal Priestess EP, which combined their patented subversive hilarity with an up-to-date metallic sheen provided by former Edgar Winter Group prodigy Dan Hartman. Then they set to work on their 1982 metal masterpiece, Coup D’État. Coup… would have an influence that far outweighed its sales figures. Most American metal bands were still stuck somewhere in the mid-70s, and the shock rock of Alice Cooper had grown stale. The confrontational and subversive tactics of the Plasmatics would have a significant impact on underground metal in the 80s and beyond.

The Plasmatics’ move to metal came at a fortuitous time. Kiss, who had been struggling in the early 80s, signed the Plazzies up as their support act. By doing so, they were able to regain some of the danger and shock-rock street cred that their concerts had lost, and the Plasmatics were able to corrupt young minds in towns they could never play alone. Kiss would prove later to be invaluable allies.

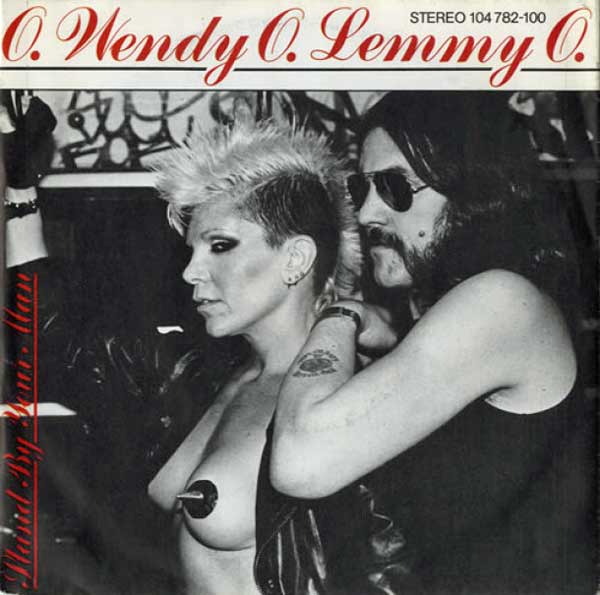

Fresh off the Kiss tour, the Plasmatics found themselves the object of another big metal band’s admiration. Swenson was approached by Motörhead manager Doug Smith with the idea of having Wendy join Lemmy and the boys for a mauling of Tammy Wynette’s hayseed weepie Stand By Your Man. Plans were made for Wendy to rehearse with Motörhead in New York. Things didn’t go smoothly. “Fast Eddie and Lemmy were having some problems. They weren’t talking,” Swenson recalls, adding that Motörhead “were fairly serious meth addicts”.

After attending a raging after-show party following an Ozzy Osbourne gig at Madison Square Garden, Motörhead failed to show up for rehearsal. Another session was booked in Toronto, but a row with Lemmy caused Fast Eddie to storm out of the studio – and, ultimately, the group itself. Eddie later said his dislike of Wendy and the duet was the reason for his departure from Motörhead. Undaunted, Swenson and Wendy would remain friendly with the band, and Swenson would later go on to direct their Killed By Death video.

Following the Kiss tour, Gene Simmons had expressed interest in producing the next Plasmatics LP, but the band name was tied up in a contract dispute. “We were having a fight with Capitol Records,” Swenson recalls. But, he adds, “We realised that if we didn’t use the name we could get it out six months earlier.” Swenson says Simmons’s interest was focused not on the Plasmatics as an entity, but on Wendy herself: “Gene wanted to produce a Wendy O record – he didn’t care what it was called.” Thus sessions began for the 1984 WOW album.

Some Kiss fans have wryly noted that WOW was Kiss’s best 80s album. Simmons agreed to produce on the condition that he was able to choose which musicians to use, so not only did he take over bass (under the pseudonym Reginald van Helsing) and co-songwriting work, but he also persuaded Paul Stanley, Ace Frehley and Eric Carr to sit in on the sessions. Simmons also recommended a Kiss applicant, Michael Ray, to become Wendy and the Plasmatics’ new lead guitarist. In addition, Stanley and Simmons wrote the rousing anthem It’s My Life, which garnered Wendy some much-needed airplay.

Due to scheduling conflicts, Simmons was unable to produce Wendy’s next record, so Swenson took the reins himself. Kommander Of Kaos, again released as a Wendy O solo album, tapped into the nascent speed metal movement and brought back the breakneck tempos of the early days. Freed from legal limbo, the Plasmatics name would return for one last studio set, the outrageous concept album Maggots. But all of the controversies and bad press had taken their toll.

“We had towns we couldn’t play, promoters that wouldn’t put us on,” Swenson recalls. “We kept crossing off towns we couldn’t go into. This is how we were choked off at the end. When we stopped in 1988, we said we were going on hiatus, but we knew we were quitting.”

After a 10-year frenzy, Wendy and Rod retired the Plasmatics and settled in Connecticut. Rod began lecturing at the University of Connecticut and Wendy volunteered at an animal shelter. Suffering from depression and having difficulty adjusting to civilian life, she died from self-inflicted gunshot wounds on April 6, 1998. She was just 48.

Unjustly overlooked today, the Plasmatics are the missing link between Alice Cooper and Marilyn Manson. Theatrical shock rock had been around since Screaming Jay Hawkins in the 50s, but the Plasmatics upped the ante, and in many ways have yet to be matched. Bands such as Gwar, Mudvayne and Slipknot have adapted the shock-tactic theatrics that the Plasmatics pioneered, but none of those rock’n’roll bad boys has half the daredevil cojones that Wendy did. She was a true original, and we may never see her like again.

This feature was first published in Classic Rock issue 83, in August 2005.