We revisit this 2011 Total Guitar feature on Randy Rhoads and Ozzy Osbourne with input from Ozzy himself and bassist / songwriter Bob Daisley.

The Prince Of Darkness is on the ropes. It’s 1979, and at Le Parc Hotel in LA, Ozzy Osbourne is a madman lost in a blizzard of cocaine. Bandless, friendless, bloated and living in squalor, he has been fired from Black Sabbath and is now in free-fall. He never leaves his room, never opens the curtains, and never sees anyone except for the roadie tasked with suicide watch and babysitting. In short, Ozzy does not look like a man on the cusp of solo glory, but an obituary waiting to happen. He needs a miracle.

It took several hands to pull It took several hands to pull Ozzy out of the mud. First, the singer credits the tough love of Sharon Arden (soon to be Osbourne), the daughter of ball-busting Sabbath manager Don Arden. It was she who galvanised the washed-up frontman into forming a new band. Then came former Rainbow bassist Bob Daisley, who was the first musician to join the new Osbourne fold, despite what you might have read elsewhere. “Ozzy and I started the band,” the Australian veteran told Total Guitar. “They’ve tried their best to rewrite history, but it’s all bulls***.”

The management wanted to keep it as a UK-based band, but no guitarists were that interested, because interested, because Ozzy didn’t have the best reputation

Bob Daisley

Nobody is denying the epiphany of Randy Rhoads’ arrival, though. The 22-year-old Quiet Riot guitarist was no Sabbath fan and almost bunked his audition slot, but he only had to doodle a few harmonics through a practice amp for Ozzy to promise him a call-back. “I’d never auditioned anyone, and I was all over the f***ing place,” the singer told TG. “But f***ing hell, when I first heard Randy play, it was poetry in motion. I thought, ‘Wow, I’m onto a great thing here.’ Who knows why we worked so well. Who knows the answer to anything? But sometimes you’ll meet a girlfriend and it’s more than just a f***ing night in the sack.”

“Ozzy said all he’d heard all day was guys trying to play like Tony Iommi,” Randy once noted. “He appreciated that I was playing my own style.” There is a romantic notion that Osbourne and Rhoads shook on their partnership right here. Actually, says Daisley – who kept a diary from 1976 and wrote a tell-all autobiography called For Facts Sake! – the singer then left LA for his home in Stafford, England, and Rhoads only re-entered the frame after another guitarist was fired.

“That’s when Ozzy said, ‘Well, I met this great guitar player in LA,’” Daisley explains. “The management wanted to keep it as a UK-based band, but no guitarists were that interested, because Ozzy didn’t have the best reputation.”

Reluctantly, the management flew Rhoads to London, continues Daisley. “Ozzy and I went into Jet Records in about October 1979, and Randy was already there. Now Ozzy had told me [that] Randy was a guitar teacher at his mum’s school in LA, so I anticipated a guy with a pipe slippers, cardigan and glasses. I walk in and see this young guy; his clothes were very fitted, his hair was perfect, his nails were manicured. I actually said to Ozzy: ‘D’you think he’s gay?’”

The title came because Randy had an effect that was making a sorta psychedelic chugging sound through his amp. Randy and I were train buffs, we collected model trains, and I said, ‘That sounds like a crazy train

Bob Daisley

But when Rhoads plugged in, the planets aligned. “When we finished our first jam,” recalls Daisley, “we said at the same time, ‘I like the way you play.’ He was confident and precise; he had the influence of bluesy players like Hendrix, Blackmore and Jeff Beck, but the classical side gave him another dimension.” So after a decade spent cowering beneath Iommi’s iron fist, Ozzy was back from the dead with a band that nurtured his talent, rebuilt his confidence, and even transposed keys to suit his doomy bark.

“In Sabbath,” Ozzy says, “I’d have to put my vocals on whatever key they put the song in, and sometimes I couldn’t reproduce it onstage. But Randy was like, ‘Come on, maybe you should try it in this key.’”

“It really was a band,” agrees Daisley. “We were meant to come together. We fed off each other. The music side was more me and Randy: we’d sit on chairs opposite each other, playing the instruments and putting the songs together. I wrote the lyrics. Ozzy was very good at the vocal melodies. The first songs we wrote were Goodbye To Romance, I Don’t Know and Crazy Train.

"That signature riff [for Crazy Train] in F# minor was Randy’s, then I wrote the part for him to solo over, and Ozzy had the vocal melody. The title came because Randy had an effect that was making a sorta psychedelic chugging sound through his amp. Randy and I were train buffs, we collected model trains, and I said, ‘That sounds like a crazy train.’ Ozzy had this saying, ‘You’re off the rails!’ so I used that in the lyrics.”

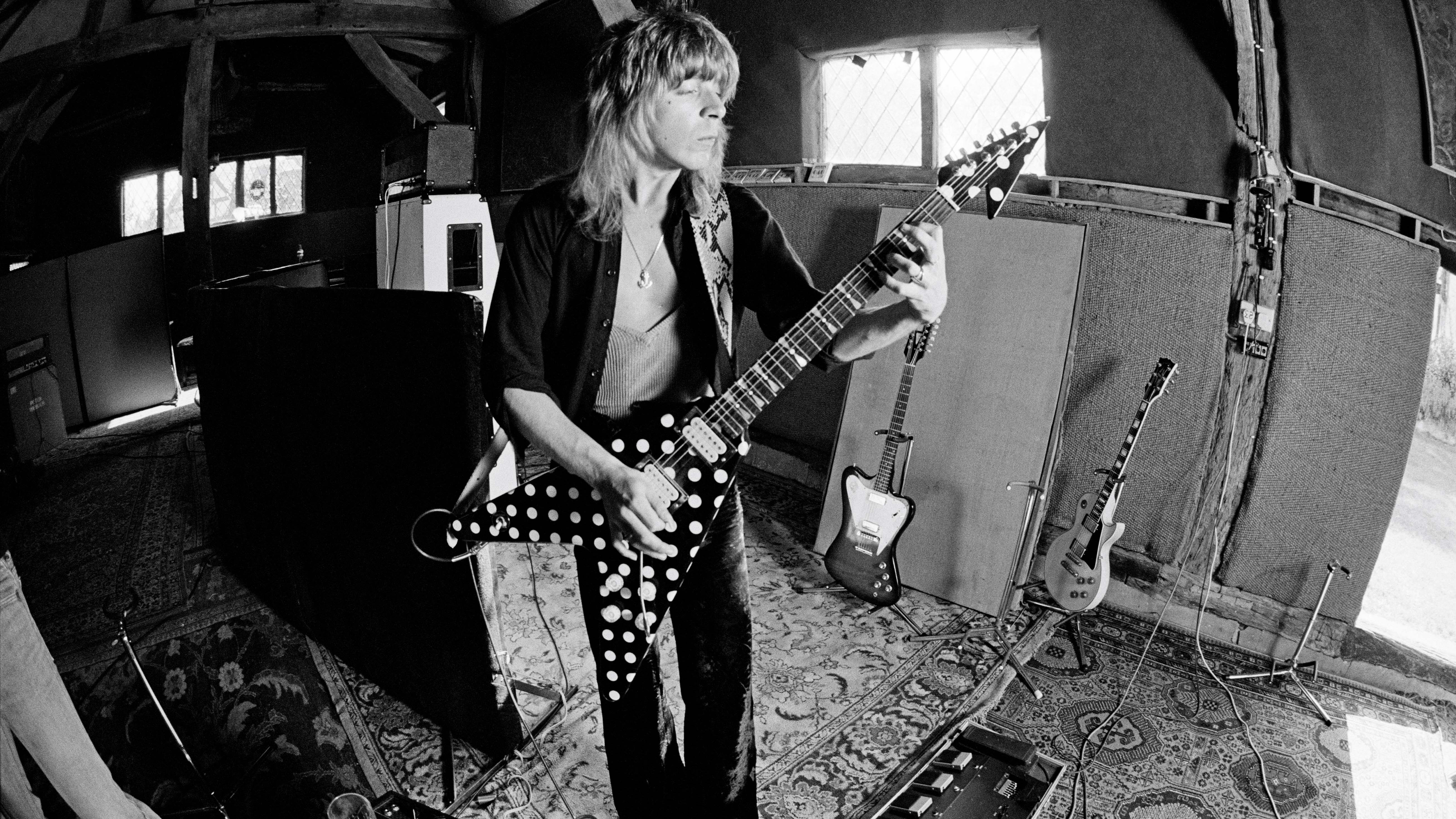

The truth behind Randy's iconic V…

Axes don’t get much more iconic than Randy Rhoads’ polka dot V. Widely assumed to be a Charvel, it was actually commissioned from the LA luthier Karl Sandoval in 1979, who charged $738 and delivered the model shortly before Rhoads left Quiet Riot.

The spec was half metal, half rock, with a mahogany body and dual-humbucker configuration of DiMarzio PAF (neck) and Super Distortion (bridge) hinting at Randy’s taste for Les Pauls. Meanwhile, a super-flat Danelectro neck and Strat tremolo gave his virtuosity free reign.

The V looked cool, played fast and the top end made it the primary choice for both Blizzard Of Ozz and Diary Of A Madman, scorching through an old-school 100-watt Marshall stack with no preamp. Another vital ingredient of the Rhoads sound was an AMS 15-80 delay, used with a voltage-controlled oscillator. The best examples, says Max Norman, are he rhythms on Crazy Train: “You’ll hear there’s a real grind to them. That particular sound comes from the AMS. It’s almost like a flange, but not quite…”

Mr Crowley, meanwhile, was built on Randy’s chord structure and blown skywards by a precocious lead starburst of legato and alternate picking. As for the funereal organ, says Daisley, you can thank a prematurely aged synth player for that: “It was about Aleister Crowley, which was Ozzy’s idea, but that little intro came from a keyboard player who was sent down [later recorded by current Deep Purple keysman Don Airey]. Ozzy and I called him Grecian 2000, which was an over-the-counter hair treatment, ’cos he had grey hair!”

When drummer Lee Kerslake came onboard, the band was complete, and in March 1980 the Ridge Farm Studios in Surrey trembled as the Blizzard Of Ozz crew rolled in. Ozzy’s dwindling fortune only stretched to a four-week booking, and he wasn’t wasting time. “He’d start out pretty straight and sober, probably take a bottle of Scotch in there with him,” engineer Max Norman said in an interview with KNAC. “He’d be nipping away at the Scotch as we were doing a song… If he wanted to take a p*** in the middle of the take, he’d do it right there on the floor.”

“Ozzy would go over the top”, confirms Daisley, “with both albums for different reasons. With Blizzard, he was getting over being fired from Black Sabbath – he told me it felt like a divorce – and having doubts about the future of his career, because the stuff we were doing was almost considered ‘old hat’ or ‘dinosaur’. He was the one who drank most, smoked the most pot. I think Randy did coke a few times, but he wasn’t really one for drugs. Sometimes we’d smoke pot in the studio, have a joint and work on a new part of a song.”

If anybody f***ed up, we started again

Bob Daisley

The recording method was also old school, if highly effective, with the basic rhythm guitar, bass and drums all captured live. “If anybody f***ed up, we started again,” grins Daisley. “There were no drop-ins or repairs like you can do now.”

Despite his casual claim that “the first album was just turn it up to 11 and if it feels good just play it”, Rhoads was chasing perfection. He worked 12-hour shifts in the control room, overdubbing rhythms and painstakingly chasing down solo ideas over a looped backing track. Once a solo was written, he would double- or triple-track it. And not via copy-and-paste technology, but by playing it identically multiple times (a mind-bending feat, given the speed of his leads).

He was the best guy at overdubbing solos and tracking them that I’ve ever seen. I mean, he used to blow me away

Max Norman, engineer

“If you listen to Crazy Train real close,” Norman once told Jas Obrecht, “you’ll hear there’s one main guitar around the centre… And there are two other guitars playing exactly the same thing, panned to the left and right, but back somewhat. And actually what happens is [that] you don’t hear them – you just hear it as one guitar. He was the best guy at overdubbing solos and tracking them that I’ve ever seen. I mean, he used to blow me away.”

Most Blizzard material was recorded either with Rhoads’ polka dot Sandoval V or a Gibson Les Paul through a 100-watt Marshall stack. But membership in Ozzy’s band hadn’t killed Randy’s classical spark, and these tools of the metal trade were downed for a 50-second conservatoire instrumental, Dee, which provides a breather amid the headbangers. To create it, Rhoads worked alone in the studio late at night, mic’ing his Martin with an AKG 451, then doubling the part on a classical guitar. For guitarists, it rounds off a desert-island album.

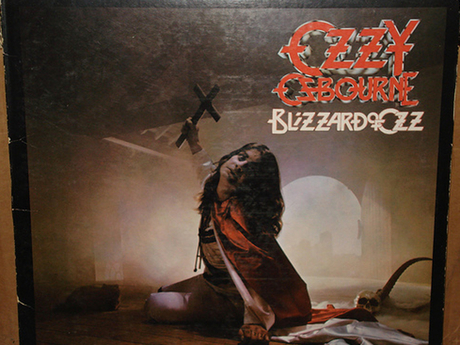

Blizzard Of Ozz was undeniably great. Unleashed in September 1980, it hit the metal scene like a wrecking ball, flicked two fingers at the flailing Sabbath and provided the year’s hottest setlist when the band took it on the road.

“I remember we were in a hotel in Canada, and there was a classical piano player,” recalls Ozzy of touring japes. “Randy just said, ‘Do you mind if I join you?’ I’m thinking, ‘What the f*** is he doing now?’ Randy got his little Pignose amp and Les Paul from his room and starts playing classical. The guy was impressed… But then Randy starts throwing rock ’n’ roll shapes in. It was f***ing hilarious!”

Originally, the band was called The Blizzard Of Ozz. We’d all agreed on that, including Ozzy and the label

Bob Daisley

Not everyone was laughing, though. By this point, says Daisley, what had started as a band was being repackaged as Ozzy’s solo project, which was confirmed when the album arrived back from the pressing plant.

“Originally, the band was called The Blizzard Of Ozz. We’d all agreed on that, including Ozzy and the label. It wasn’t ‘the Ozzy Osbourne solo record’: that’s absolute b***cks. We’d said to the company: ‘We don’t mind if you put something like “Featuring the voice of Black Sabbath.”’ But when they put the record out, in smaller writing it said Blizzard Of Ozz and in bigger writing, ‘Ozzy Osbourne’, which made it look like an Ozzy solo record called Blizzard Of Ozz. So we were double-crossed.”

Despite growing friction, the line-up was still able to pump out the classics when the label pushed for a follow-up. “After we came off the road,” says Daisley, “we started the writing for Diary Of A Madman. I remember when we put the title track together. Randy had the basic riff, part of which came from a classical piece that one of his teachers gave him. It had weird timings, and Randy, Lee and I put it together musically, because Ozzy had been away for a couple of days. When he came back, we said, ‘Check this out.’ Because it was in a weird timing, his first reaction was: ‘Who the f*** do you think I am? Frank Zappa?’ Those were his words!”

As for Over The Mountain, when Randy came with that basic riff, it wasn’t played the way it ended up. I think he played it with 4ths or maybe 8ths, and I said, ‘Play it with 16ths’, and he did

Flying High Again was more straightforward, with Rhoads’ glam-crunch riffing twinned to Daisley’s coke-inspired lyric. “Randy had the opening riff and I wrote the middle section where it changes to the F#,” says the bassist. “It’s a sort of drugs song: I went into Ozzy’s little bungalow at Ridge Farm one afternoon with my pad and pen, and he and I did a couple of lines of coke.

“As for Over The Mountain,” adds Daisley, “when Randy came with that basic riff, it wasn’t played the way it ended up. I think he played it with 4ths or maybe 8ths, and I said, ‘Play it with 16ths’, and he did.”

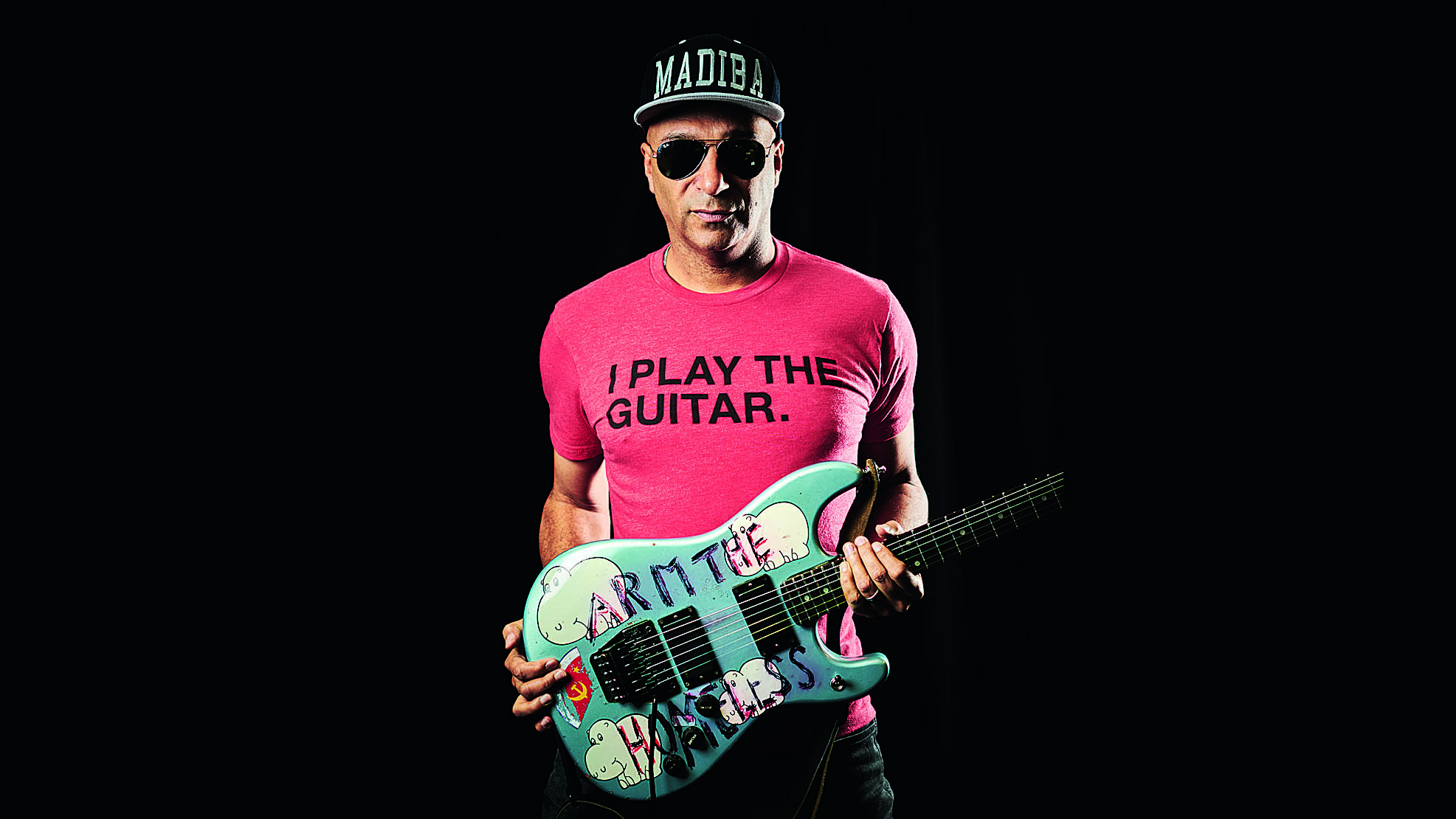

Tom Morello on Randy Rhoads: "To me, he's the greatest hard rock guitar player of all time"

With a US tour booked, the label only allowed the band a six-week window at Ridge Farm. Based on interview testimony, that didn’t seem enough for Rhoads. “The material came out shining, but I was a bit lost for licks and what to do on it,” he once noted. “I really cringe about some of the songs. I never got to put a solo on Little Dolls… The one that’s there is a guide solo.”

Likewise, he shrugged off the lead in Over The Mountain: a thrill-ride of pull-offs and vibrato. “The first lick in that section is in E minor,” he said. “The next break is just a series of real quick double pull-offs to open strings, with a whammy bar dive added at the end. That’s all there is to it. The rest of it is just, oh, noise.”

Nevertheless, everyone else agreed that Rhoads had blossomed between the two albums, and heard in hindsight, his Diary parts do seem more visionary and ambitious, from the swells and selector flicks of rock ballad Tonight to the seismic brutality of Believer.

The album’s frequent drop-tuning to E flat, Rhoads reflected, was a happy accident. “The tuner we had was miscalibrated and I began to like the sound… It just gives you a meaner sound overall.”

Talking to you now, in my head I can see the f***ing accident again

Ozzy Osbourne

Meaner, leaner and more sophisticated, Diary Of A Madman was arguably the stronger of the two albums. It seemed like a tantalising hint at what the line-up would do next, but turned out to be a maddening full stop. It should be noted that the sacking of Daisley and Kerslake in 1981 remains contentious, with multiple versions of events pinballing around the press.

Daisley would return for 1983’s Bark At The Moon, this time flanked by Jake E Lee on guitar. Tragically, Rhoads had died in an accident on 19 March 1982, after accepting a ride in a light aircraft during a tourbus stop-off in Leesburg, Florida. The plane clipped a wing on the band’s bus and span into a house, which killed all aboard. “Talking to you now, in my head I can see the f***ing accident again,” says Ozzy. “It never leaves you. Having children of my own, that’s gotta be a parent’s worst f***ing nightmare, when a kid dies before them. It breaks my heart.”

The dream team had splintered and nothing would be the same. Bark At The Moon turned out to be the first of several fine albums, yet it’s no insult to argue that Osbourne never quite matched that opening run. “The two albums Randy played on were f***ing monsters,” he sighs. “They still sound great to this day.”

To the fans, they were triumphant, packed with visionary playing. But to those who created them, Blizzard Of Ozz and Diary Of A Madman will always be tinged with sadness. “Of course, I still think about Randy,” concludes Ozzy. “The usual question is: what do you think Randy would be doing now? It’s an impossible f***ng question for me to answer.”