Thomas Waber isn’t a man given to unnecessary histrionics. The 48-year-old German is the model of Teutonic directness. His conversation is articulate and efficient, his answers blunt and honest. So when he describes something as “an existential crisis”, you know he’s not exaggerating.

The flashpoint he’s referring to came in the summer of 2009. The label Waber spent 16 years building, InsideOut Music, had gone from fringe concern to progressive rock powerhouse. They had released records by Spock’s Beard, Transatlantic, Symphony X, The Flower Kings, Devin Townsend and dozens more acts who helped shape the landscape of modern prog.

In the 1990s, the mainstream music industry viewed the prog scene with the same affection it would a leper colony – studiously keeping a safe distance. But the success of InsideOut took everyone by surprise. Everyone except Thomas Waber, at least.

In 2000, Waber signed a deal with a major German distribution company. The deal would extend InsideOut’s reach hugely across Europe and into America. It meant they could put out more records, offer heftier advances, sign bigger names. But the upward swing shuddered to a halt in 2009 when InsideOut’s parent company filed for bankruptcy. It was no fault of Waber’s, but the result was the same: one of prog’s figurehead labels was perilously close to having the plug pulled on it.

“Was I worried? Of course,” he says. “That was a very difficult time.”

Thanks to a combination of business smarts, brinksmanship and sheer bloody-mindedness, Waber managed to save InsideOut. But he didn’t just drag the label back from the edge of doom. He found a way to give it a new lease of life. Nearly a decade on from that near-extinction event, InsideOut are stronger than ever. And 25 years after the label was founded, it stands as one of the great bastions of the genre.

“InsideOut are 100 per cent responsible for prog’s ongoing success over the last 25 years,” says ex-Dream Theater drummer Mike Portnoy, who’s known Waber since the early 90s and whose bands Transatlantic and Sons Of Apollo have both released albums on the label. “They carried the flag when nobody else would. So many bands have had an outlet because of InsideOut.”

Thomas Waber is a child of the 80s. The first Genesis album he bought was Abacab, at the age of 11. He grew up feeling like he’d missed out on prog’s golden era. “When I started listening to this kind of music in the early 80s, I thought, ‘Wow, I missed all the good stuff, because it all happened in the 70s,’” he says.

We’re sitting in a boardroom in the London offices of InsideOut’s parent company, Century Media, who are in turn owned by major label Sony Music. For someone who is an outlier on the bigger music industry spectrum, he looks at home here. But it’s a role he’s grown into. He’s definitely a prog fan who started a label all those years ago, rather than a record industry executive who spotted in niche in the market. He laughs at the thought of it being anything else. “If you were a record executive who wanted to make money in the 1990s, prog is not what you should have got into,” he says.

Waber may have felt that he missed out on prog’s glory days, but there was still plenty to keep him interested. He gravitated towards the neo-prog movement that blossomed in the UK, and Southampton’s IQ in particular. His early career would become inextricably linked with that of the band.

“I met Thomas when him and a few of his mates came along to a couple of IQ gigs on the Are You Sitting Comfortably? tour in Germany,” says IQ guitarist Mike Holmes. “They just used to hang around. He wasn’t involved in the music industry at that point. He was a fan but he was very opinionated. I don’t mean that in a bad way – he had a lot to say, which was pretty good.”

Holmes points to a band rehearsal attended by Waber just after their second singer, Paul Menel had left, as indicative of his character. “Thomas encouraged us to go after our previous singer, Pete Nicholls. He was very vocal about that. And we did. And then we started talking about a new record, and how we would record and release it.”

IQ had recently parted company with their label, Phonogram. Rather than go through the arduous process of seeking out another deal, they decided to set up their own record company, Giant Electric Pea. Waber, who was studying economics, was brought into the fold. “It was myself, Thomas, our keyboard player Martin Orford and our lighting guy Laurence Dyer,” says Holmes.

Waber curtailed his studies to throw in his lot with GEP. “It was naïve,” he says. “But I guess it wasn’t the worst decision I made.”

The first album released on Giant Electric Pea was IQ’s J’ai Pollette D’Arnu, a collection of live tracks and B-sides that came out in June 1991. The initial plan was to focus on IQ’s own music, but the remit soon broadened. The label became home to fellow neo-prog outfit Jadis, rising Brit band Threshold, US nu-prog heroes Spock’s Beard and more. The music industry might not have been interested in prog, but Waber and the members of IQ figured that there were still plenty of people out there who were.

Waber himself was deeply embedded in the scene. He’d befriended the members of Dream Theater early in their career. “He was following us throughout Germany on that tour,” says Mike Portnoy. “He was like a Deadhead, going from show to show. I got to know him as a fellow prog fan, talking about Yes and Genesis and Pink Floyd and all that stuff.”

Waber had correctly spotted their crossover potential. “They opened up the heavy metal scene to prog,” he says now. “Before that, no one outside of that world would buy it, no magazines would write about it.”

Dream Theater’s against-the-grain success confirmed to Waber that there was a market for progressive music in the 1990s. What there wasn’t was an infrastructure: there were few labels beyond the odd bedroom-run cottage industry, no professional distribution companies interested in dealing with the records that did come out. “There was a scene and infrastructure in the UK, but the rest of the world was dead as far as the genre was concerned,” he says.

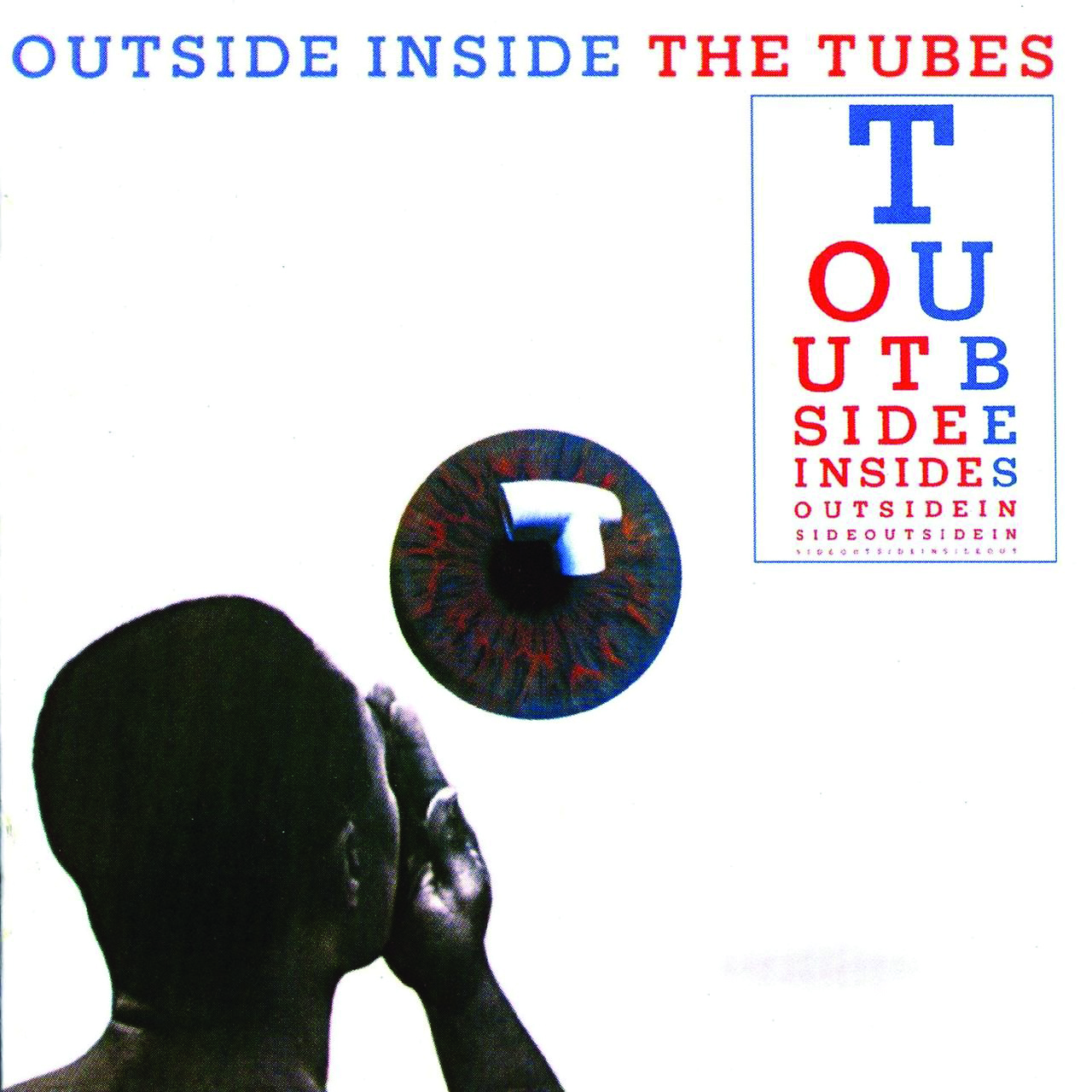

The situation needed rectifying. Giant Electric Pea were doing well, but they were based in Britain and didn’t provide a steady income for Waber. In 1993, while still involved with GEP, he decided to set up a new company in Germany with a friend, Michael Scmitz, that would help get records that he liked into the hands of people who might also like them (Scmitz left the company amicably in 2006). For the name he took inspiration from an album by one of his favourite bands, The Tubes, that was lying on his desk. Its title was Outside Inside. Waber liked the sound of it, so he reversed the wording. InsideOut was born.

More than once, Waber pushes back hard at the suggestion that he’s a figurehead for the prog scene. “It’s never been about being on a mission for prog,” he insists. “I grew up on 80s prog, but I’m not a prog nerd like some guys. It was more like, ‘Why aren’t IQ selling more albums?’ or ‘Hey, I like these bands, let’s work with them.’”

That ethos drove InsideOut from its inception. Waber describes the label’s early days “as a little convoluted, a little blurry”. There was an overlap with Giant Electric Pea, for whom he continued working. The new label initially distributed albums by GEP bands such as IQ, Threshold and Spock’s Beard. In 1994, Waber licensed former King Crimson violinist David Cross’ solo album, Testing To Destruction after being given it at a music trade fair. “I was into King Crimson when I was young and I thought, ‘That could be a cool thing to do.’”

Testing To Destruction – catalogue number IOM001 – became InsideOut’s first proper release. Over the next few years, the label’s identity began to coalesce around the bands Waber picked up: neo-prog (embodied by America’s Enchant and Switzerland’s Clepsydra) with a side order of prog metal (courtesy of the likes of Italy’s Eldritch and New Jersey’s Symphony X). Yet there was no InsideOut sound in Waber’s head. The roster was built on entirely more pragmatic foundations.

“Signing bands is a mixture of availability, whether they’re actually interested in working with you and whether you actually like those bands or see something in it that would work,” he says. “It’s always worked like that. You get presented with opportunities – you take some of them, You don’t take some of them. Some of them you don’t want to take.”

He cites Symphony X as “the first significant actual signing we made”. He had been tipped off about them by a PR company the label worked with. “I listened to them and thought, ‘Wow, that’s pretty special.’ And I could see how that would do well with the fans that liked Dream Theater.’” (He was proved right: Symphony X’s 2007 album Paradise Lost is InsideOut’s biggest-selling release.)

Conversely, Waber passed on the possibility of signing Porcupine Tree in the late 90s. The British group were still on their original label, Delerium, at the time, and were looking for a bigger home. “They were a different band back then,” he says. “I did see the potential, but I didn’t see that it would become as big as it did. It’s not like those early Porcupine Tree albums weren’t good, but they were more niche. Then they changed gears and all of a sudden they attracted a bigger audience.” He shrugs. “You can’t foresee something like that.”

InsideOut did just fine without Porcupine Tree. For years, they operated under the radar of the mainstream music industry: big enough to thrive but small enough to not be interesting to what Waber calls “bigger players”. That suited him fine.

“If the bigger players come in because they see an opportunity, you’re going to have a problem,” says Waber. “The thing with prog is that people in the mainstream music industry don’t give a shit about it. Although there’s always two or three people at a label that go, ‘I’ve never really been able to talk about this here because it’s really uncool, but I’ve always been a huge prog fan…’”

All that changed at the turn of the millennium. Waber had beefed up the label’s roster with some established names: King’s X guitarist Ty Tabor, the Mike Portnoy-led supergroup Transatlantic, Devin Townsend, Spock’s Beard. The latter’s fifth album, 2000’s V, had marked a significant step change for the label. “All of sudden things changed, because it sold really, really well,” says Waber. “They were a band who were starting to break through to a more mainstream audience.” He smiles wryly. “We had Spock’s Beard and Transatlantic going like that, and Neal [Morse, Spock’s Beard frontman and Transatlantic keyboard player] called one morning and says, ‘I’ve got to tell you, I’ve found God and I’m going to quit those bands.’ You kind of go, ‘What the fuck? It doesn’t make sense.’”

The occasional bump didn’t slow InsideOut down. They were becoming too big for the music industry to ignore. In 2000, heavyweight German distribution company SPV bought into the label. Suddenly, InsideOut had more reach, more money and more status.

Over the next nine years, the label flourished. With few genuine competitors, it owned the road when it came to contemporary progressive rock. It put out albums by veterans (Steve Howe, Steve Hackett, Swedish pioneers Kaipa) and newer artists (Pain Of Salvation, The Tangent, Kino) alike. Its release schedule went from a handful of records every year to dozens. InsideOut was flying. And then everything nearly came crashing to the ground.

Bankruptcy stories are complex and rarely interesting, and that of SPV is no exception. But when the company’s owners began insolvency proceedings in May 2009, its impact on InsideOut was immediate. The administrators had frozen SPV’s assets – and by extension, InsideOut’s with them. Yet bills still needed paying, and Waber was liable for potentially ruinous personal damages if it they weren’t.

“It happened so fast,” recalls Waber. “You’ve got to do whatever you can to stay focused and try and sort out the situation.”

The clock was ticking. As Waber tells it, InsideOut was an asset that SPV could have sold but they weren’t ready to let go of it “because it didn’t fit in with their plans”.

Waber decided he had only one option. He told SPV’s owners that if they didn’t cut InsideOut loose, he would hit the nuclear button. “It was, ‘Okay, either, if you don’t sell us in the next seven days, I’m going to go and declare bankruptcy myself.’”

It was a risky gamble that could have meant the end of everything Waber had spent the previous 16 years building. But he knew that if he could only extricate himself and his label from SPV’s mess, there was still a future for InsideOut. “There was a feeling of, ‘People are buying these records and listening to these bands,’” he says. “‘There’s something good here. Someone’s going to help us out.’”

He held his nerve and his instincts proved right. SPV capitulated, and German label Century Media swooped in to save InsideOut. They had survived their existential crisis. The future was secure.

According to Waber, the last decade has been as smooth as it can be for a traditional record label in the digital age. There have been bumps: the departure of InsideOut mainstays Ayreon to Dutch label Mascot was one source of frustration. “You think, ‘Did that have to happen?’ Then the next thing, you sign Kansas and go, ‘This is great.’ You win some you lose some.”

During the SPV years, Waber concentrated on the business side of things as much as he did scouting out bands. Since the turn of this decade, he’s been able to concentrate on what he likes the most: signing and nurturing bands.

“Century Media said, ‘Look, you should focus on what you do best and just get on with it.’ I still have responsibilities, but I don’t have responsibility for the whole company any more.”

These days, the label’s roster includes contemporary bands such as Riverside, Leprous, Bent Knee and Haken alongside the likes of Steve Hackett and Devin Townsend (via his Hevy Devy imprint). Yet Waber rarely signs brand new bands without a track. He thinks there has only been one in the label’s history: Magnitude 9, who released their debut album on InsideOut in 1998. This is partly down to caution, but also a product of most new music he’s sent simply not being up to scratch.

“Some of the stuff we get sent is just ridiculous,” he says, an uncharacteristic flash of frustration in his voice. “We get death metal bands sending stuff in, basically stealing your time. Out of 300 things that come in, there are maybe 20 that are relevant to the label and maybe one thing where you think, ‘That’s not bad, but it’s still not worth signing.’”

That’s not to say they don’t believe in new music. In 2017, they signed US art rockers Bent Knee for their fourth album, Land Animal. “InsideOut are definitely the big label in that scene,” says Bent Knee singer Courtney Swain. “I don’t know if it’s a holy grail for bands, but they have a muscle that other labels don’t have. We definitely reached more people with them.”

Waber estimates the label have released around 500 albums. Blind faith in whether or not a record would sell gave way a long time ago to accurate forecasts. Sometimes too accurate.

“You think, ‘These bands should sell,’ and then they sell exactly what you thought they would sell. It’s never been, ‘Wow, how did that happen?’ It’s always been, ‘Why has nothing ever done better?’”

The answer, as he sees it, is simple: there’s a ceiling on prog. “It’s a niche genre. There aren’t many bands that have managed to cross over: Dream Theater, Porcupine Tree, Spock’s Beard before Neal found God. The prog scene has always been fairly insular.”

He remains wary of that us-and-them mentality, especially when it’s internalised within the scene. The barriers that have come up between fans of the genre’s original masters and those who lean towards its new generation frustrate him. “You’ve got people who like Yes and Genesis and Steve Hackett and everything else, and they’re really snobbish about that. They would never check out Leprous or Haken or Animals As Leaders. Whether they’d like it or not, they wouldn’t even give it a try.”

He’s less frustrated at having to deal with the caprices of musicians. His no-bullshit conversational manner extends to his business practices.

“Dealing with bands is our daily bread and butter,” he says. “I guess you sometimes wonder if you should have become a psychiatrist or worked in a kindergarten instead of setting up a record company, because that’s what it’s like with artists a lot of the time. But the way I work is that I’m very upfront and very blunt. People know that. And if they don’t, they know it within five minutes of being in a room with me. Some people are, like, ‘Who’s this idiot?’ But most people appreciate honesty, because no one in the music business tells you the truth.”

Are you on good terms with everyone who’s left the label?

“I’m on speaking terms,” he says. “When you start out, everyone is close, everything is a big family. But at some point you’ve got to be able to step back. If you can do that, you’re fine.”

“Oh, Thomas is very upfront with his opinions,” says Bent Knee violinist Chris Baum with a laugh. “We’ve definitely had some interesting discussions with him. But his track record proves that he’s right.”

Mike Portnoy agrees: “Most of the time, I don’t want to hear the opinion of someone who works at a record company,” he says. “I usually go the opposite way. Thomas is one of the few people who I’ll listen to, and what he says is usually spot on.”

InsideOut’s existential crisis is a distant memory today, The label is in as healthy a position as a modern record company can hope for in 2018. Over the past 12 months, they have released new albums by Spock’s Beard, Kino, Riverside, Haken, Roine Stolt-fronted supergroup The Sea Within and Beardfish/Big Big Train guitarist Rikard Sjöblom’s Gungfly, among others. Next year, there will be high-profile new albums from Steve Hackett, Devin Townsend, Nad Sylvan, Tim Bowness and Bent Knee.

Significantly, 2019 will see Dream Theater releasing their first ever album on InsideOut, more than a quarter of a century after Waber first met them. It does more than just bring their relationship full circle – it represents the convergence of two paths that have simultaneously but separately charted the journey of modern prog from the dark days of the early 1990s to its current bright renaissance.

Thomas Waber isn’t the kind of person to oversell the part he or his label has played in the genre’s resurgence. As he reiterates one last time: “I’ve never been on a mission for the prog scene.” But if nothing else, the anniversary of the label he founded 25 years ago does occasionally give the man who once worried that he’d missed out on prog’s golden era pause for thought.

“I look back on it and I realise that I’ve witnessed a lot of stuff first hand,” he says. “Stuff that happened that people who are getting in the genre now, or even 10 years ago, didn’t experience. That makes me think we’ve done something right.”

This article originally appeared in issue 94 of Prog Magazine.