Dangbo… o… Dingbo… o. Every Bhutanese story begins with these two words, to either mean that once there was a ‘Dangbo and a Dingbo’ (folk figures) or to signify a passage of time, that the tale is from a long time ago. If ‘Dangbo Dingbo’ are used with a short sound, it indicates the story is not from so far back, but if the last syllable is stretched, then it means the tale is from a long, long time ago.

In a culture of orality, this makes perfect sense.

Kunzang Choden: preserving folk tales

One of Bhutan’s foremost novelists, Kunzang Choden, and the first to write a tome in English (The Circle of Karma), has been documenting folk tales and Bhutanese stories of the Yeti, ones she had heard as a child, writing them in English for future generations. There are 24 languages spoken all over Bhutan, says Choden, and each is different from the other in tone, each with their own stories.

With a population of about eight lakh, often the only sounds to be heard amid the crisp mountain air are of a river gushing by, bird song and the soft tinkling of bells from Buddhist temples. Bhutan, popularly called the last Shangri-la, is a magical place, though locals, just like in the Northeast of India, do not want their land to be exoticised. Yet, with the technological advances of the 21st century and the fear that this culture may be forgotten, they want to do everything they can to preserve its rich heritage and legacy.

Karma Phuntsho: tracking songs, rituals and symbols

During Bhutan Echoes’ recent Drukyul’s Literature Festival, we spoke to writers, designers, historians and artists who are mapping the country’s rich past. Like Choden, who is chronicling oral traditions, scholar Karma Phuntsho is ensuring that endangered cultures stay alive through his fascinating “project of intangibles” that he has undertaken since 2013.

The Loden Foundation, which he founded, has over 3,300 hours of ethnographic documentation featuring songs, dance forms, stories, rituals, human-nature connections, motifs and symbols (such as mandalas) and other aspects of life from all 20 dzongkhag or districts of Bhutan. It has 10 documentary films ready for launch. “There is a lot Bhutan can share with the world, not just its idyllic vistas. Our vibrant culture, connect with nature, Buddhist ethos, and other intangibles — it’s a rich history,” he points out.

For instance, Phuntsho says in Bhutan there’s traditional literature that talks about cultural landscapes called sache (land analysis). “Bhutanese believe in invisible energy and spirits present in the environment; so when we design something we ought to be conscious of this. Coming from a Buddhist state of mind, we believe that our happiness, our well-being depends on the sensory data we receive. If we are in a chaotic environment, we will have a disturbed state of mind.”

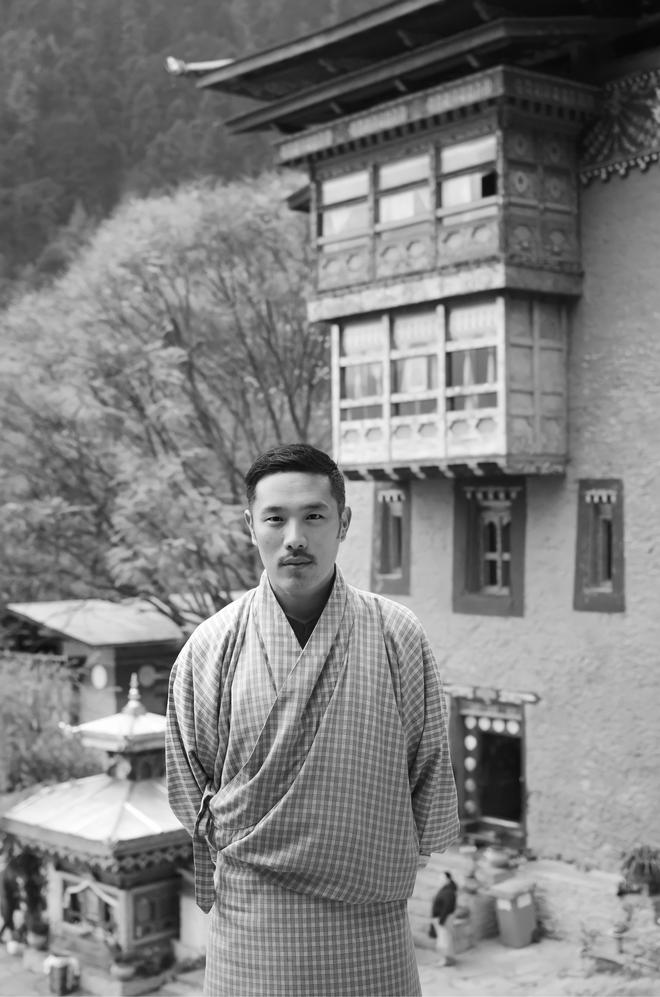

Karma Tshering Wangchuk: documenting the street

Fashion blogger, illustrator and designer Karma Tshering Wangchuk ‘Lhari’, who is just back from the Copenhagen Fashion Week, launched his book, Lhari, at the lit fest. With a pink cover, it has no relation to the Barbie movement, he quips, but to a pink rhododendron integral to Bhutan. It’s a part of the Artists’ Vision Series, a collaborative project between Australia and the Buddhist kingdom.

His journey began as an Instagram reel for his Indian friends (he went to school in Darjeeling and NIFT, Delhi) to showcase Bhutan’s way of life. When the kira (the skirt a woman wears) and gho (a man’s dress) that he photographed got noticed, he wanted to do something to contribute to a sustainable fashion industry.

He has been working since 2010 to photograph people in their traditional clothes, highlighting the textiles (woven with techniques such as the trima weft), the beautiful patterns (dragons, stupas, eternal knots, flowers), and telling stories around the fabric. His book is about Bhutan street fashion without “over-romanticising or over-curating” the looks. He decided to not make any new clothes for the “guerrilla style” portfolio shoot and borrowed from the people.

Most of all, there was no photoshopping. “The fashion industry talks about sustainability, but in Bhutan we practise it, and this tiny country, hemmed in by India and China, can offer this visual collectivism and non-performative art to the world,” he says.

Calling the subcontinent a universe within a universe, he is very keen to contribute to sustainable fashion and chronicle the rich story of textiles of the entire region — “the silk threads we use for the kiras come from Assam,” he says, unwilling to use the word ‘import’. He is about to start another interesting project, documenting textiles across Bhutan. “We are very diverse and I want to preserve this before it disappears.”

The writer was at Drukyul’s Literature Festival on invitation.