Kim Jones admits there is something disorientating about discussing one collection while in the midst of the preparations for another. It is a hot June day in Paris and we are sat, fans whirring, in a Dior showroom a stone’s throw from the Arc de Triomphe. The British designer is surrounded by pieces from his S/S 2025 collection for Dior Men, which he will show the following day. A cluster of ceramic cats by South African artist-potter Hylton Nel, one of the collection’s inspirations, are lined up behind Jones, watching on. The next day in the Val-de-Grâce show space, they will be blown up to enormous size, populating the catwalk in surreal style.

But the subject of the conversation is his A/W 2024 collection, which arrives in stores this September and was shown this past February on a rotating circular runway that eventually rose from the floor like an enormous music box. One gets the sense that Jones – a designer whose work is in constant forward movement, famously organised and often working several collections in advance – is not someone prone to looking backwards. For starters, he doesn’t have time to. As creative director of Dior Men, as well as artistic director of Fendi womenswear and couture, he produces around 30 collections a year, splitting his time between London, Paris and Rome.

That said, A/W 2024 was special, says Jones, and worthy of reflection. ‘It was a really personal show,’ admits the designer, who began the collection by looking at a series of images of the Soviet-born ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev by Jones’ uncle, Colin Jones, a former dancer-turned-documentary photographer. Taken largely in 1966 for Time magazine’s ‘A Day in the Life’ series – five years after Nureyev sensationally defected to the West in 1961 at Paris’ Le Bourget airport with the declaration ‘I want to stay and I want to be free’ – the intimate, decidedly quotidian images show Nureyev at home, shopping for magazines, and at rehearsals. ‘You couldn’t keep your eyes off him,’ the photographer said in 2011.

‘There’s so much richness in [Nureyev’s] pieces… He had an eye for luxury, he understood the finer things in life’

Kim Jones

‘My uncle had a huge body of amazing work and it was something that I looked up to, so it was wonderful to do a show that celebrated him,’ says Jones, who counts watching the photographer at work in his darkroom when he was a child as one of his foundational memories of creativity. ‘Seeing [that] in childhood, it sticks with you forever. I just took the thread and worked on it.’ That house founder Christian Dior had an enduring friendship with prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn – who would first dance with Nureyev in Giselle in London in 1962, later becoming one of ballet’s best-known partnerships – was serendipitous. ‘Everything just sort of tied together,’ says Jones.

Nureyev would also become the impetus for Jones to create the house’s first dedicated couture collection for men, which made up the final 20 looks in the show. Jones likens the contrast between the ready-to-wear and couture collections to ‘Nureyev’s theatrical life and his reality, a dialogue between the dancer’s style and the Dior archive’. An avid collector of art, archival fashion and first-edition books, the designer had poured over auction catalogues of Nureyev’s personal belongings (adding a pair of the dancer’s shoes to his collection) and was transfixed. ‘I looked at all these things that were his and just reinterpreted them for today. It’s why I decided to do the couture thing. There’s so much richness in his pieces… He had an eye for luxury, he understood the finer things in life.’

‘People want something that nobody else has’

Kim Jones

Haute couture is a distinctly Parisian phenomenon, referring to the art of dressmaking whereby each piece is made entirely by hand by skilled artisans for specific clients (such is its place in French culture, it is protected by law, with houses – only 15 currently – vetted by the Fédération Française de la Haute Couture et de la Mode). As such, couture is defined by its staggering flights of craft – a single gown can take hundreds of hours to complete – made possible through the relationship between designer and atelier. Where the designer brings imagination – a vision of a silhouette, an idea for adornment – it is ‘les petites mains’ (the ‘little hands’) who make it real. As such, it is the lofty pinnacle of French fashion, an art form made to transcend the everyday, and cannot be rushed.

Couture has been on Jones’ mind since he began his tenure at Dior in 2018, coming off a commercially and critically acclaimed tenure as creative director of Louis Vuitton menswear. His first collection for Dior, shown that summer, saw him introduce the Tailleur Oblique suit, based on a wrapped, single-breasted design first presented by Christian Dior in the 1950s for women. The house founder remains a guiding light for Jones; looking back into the Dior archive for him is ‘common sense’.

‘I look at it because of the purity, and it’s also very much rooted in menswear,’ he says. Other pieces have drawn on fabrications, embellishments and patterns – even unrealised sketches – from the archive, or play with seminal Dior pieces, like the bar jacket, which remains an emblem of Christian Dior’s meticulous eye for elegance (Jones created a version for men as part of his A/W 2022 collection).

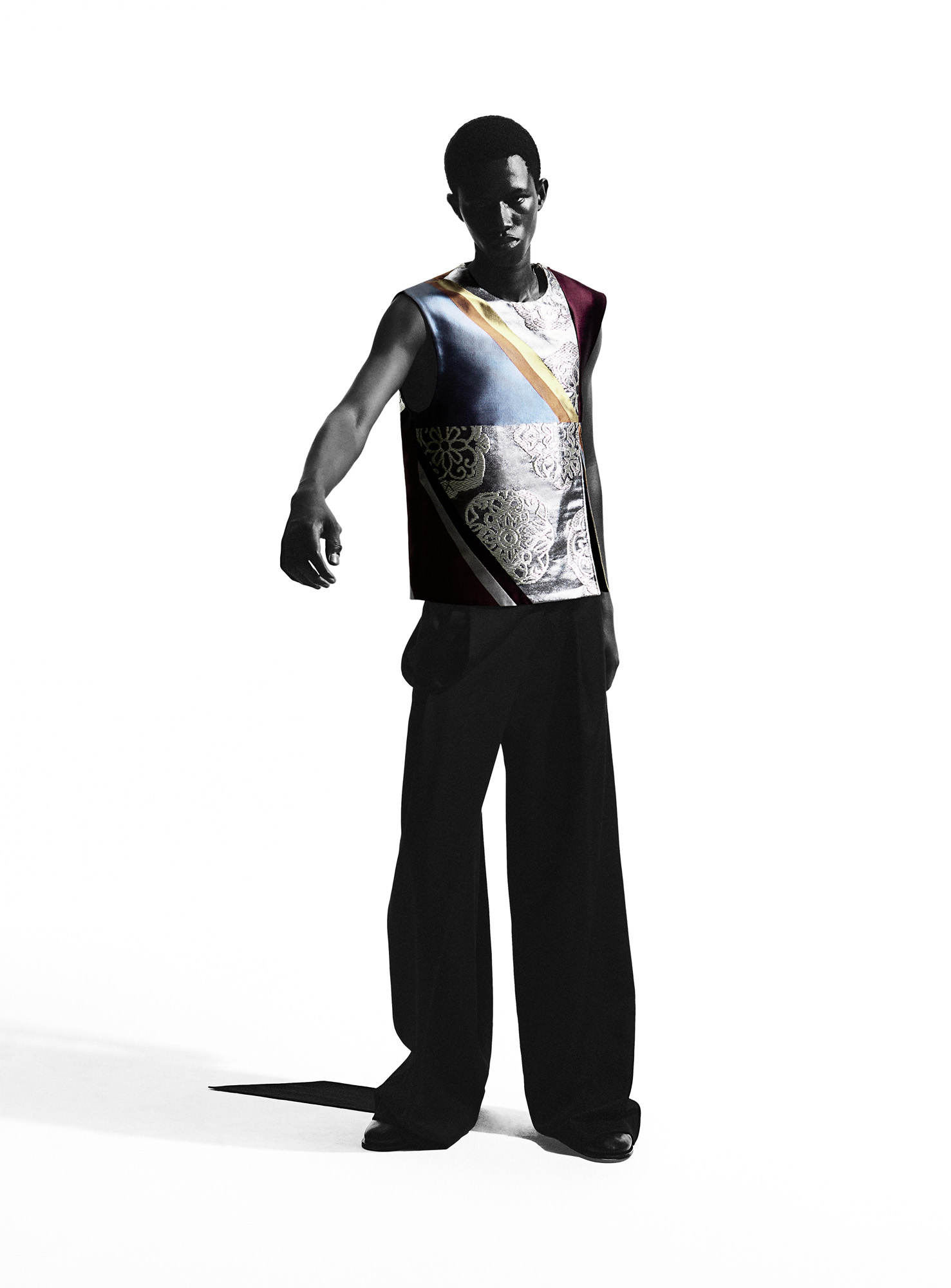

The 20 looks in the couture collection capture the splendour of Nureyev’s incandescent stage performances, while harking to pieces in the Dior archive. The embroidery from the sequinned Debussy evening gown, created by Christian Dior for Fonteyn in 1950, here adorns a men’s boiler suit. A beaded tabard top comes with a thick collar of pearls, while narrow-waist tailoring has glass-like shards of embroidered decoration around the waist. Meanwhile, a series of colourful kimonos are inspired by Nureyev’s love of the garment, with one taking ten people three months to complete in Kyoto, Japan. ‘People want something that nobody else has,’ says Jones of couture’s enduring appeal, though this does not mean that every piece ‘has to be loud’. There is also a great suit, a bomber jacket, and even denim (albeit adorned with crystal stitching).

It was all presented to the shuddering sounds of Sergei Prokofiev’s Dance of the Knights, part of the Russian composer’s ballet Romeo and Juliet, written after he moved back to the Soviet Union from the US in 1936. First performed in 1938, it would be danced in London by Nureyev and Fonteyn to a 40-minute standing ovation in 1965. Here, the dissonant avant-garde masterpiece was ‘reinterpreted’ by German-British composer Max Richter, a longtime collaborator of Jones. Richter’s recent work has seen him ‘recompose’ Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, renovating the symphony from the first note up. ‘I needed to figure out how I could fall in love with this music again,’ he said of the task, which was completed in 2012 and re-recorded in 2022.

In the vaunted Dior archive – one so filled with recognisable silhouettes, and steeped with history – Jones sees a similar task of reinvention. ‘Everything is encompassed in that score.’

This article appears in the September 2024 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

All looks from the Dior Men A/W 2024 collection. Model: Mamadou Diallo at Success Models. Casting: Ikki Casting at WSM. Grooming: Laure Dansou at WSM. Photography assistant: Cameron Koskas. Fashion assistant: Eva Rapti. Production assistant: Bertrand d’Amiens. Digi tech: Gill Cesaria.