It’s a Sunday evening, and the bar is full. There are more women than men, unusual for India, where gender stereotypes and taboos have long defined social drinking. Everyone is dressed down, and instead of the crowded partying that marked nightlife of a generation (or even a few years) ago, here at Sidecar in Delhi’s GK II — recently anointed number 18 on Asia’s 50 best bars list — the conversations are calmer and the drinks sophisticated, such as my aged Boulvadier, carefully crafted to my taste.

Post pandemic, the idea of a night out in India is changing, with millennials and Gen Z preferring sophistication over shots, the quiet luxury of crafted cocktails, and dialled-down socialising with their own “tribe” even as the quality and price of what’s in their glass gets upped. “I don’t think anyone is like ‘where’s the party tonight’,” says Jigyasa Malhotra, 26, a travel blogger from Goa, who dabbles in interior design, cleans beaches and waterfalls on weekends, and has recently brought out a made-in-Goa spiced rum, India’s first. “Things have changed a lot in the last two to three years, even in Goa. Despite so many bars coming up, I think people just want to find a place with their vibe and tribe, and stick to it.”

The pandemic with its flexi work options and the idea of making the most of the time we have, seems to have pushed the trend of conscious socialising and smaller format “neighbourhood” bars. They are the new epicentres of a culture where work meets play meets passion — all over well-made craft drinks.

“People come even during the day, with their laptops, sit by the library, meet others, and have drinks suggested by our staff,” says bar expert Yangdup Lama of Sidecar, as we talk about the evolution in India’s bar culture from the late 1990s, when he started at the Hyatt.

Now, the wheel has come a full circle as India’s drinking culture moves towards more discernment and less show. “Anecdotally, this is a big trend,” says Yash Bhanage, co-founder of The Bombay Canteen, whose bar too featured on Asia’s best list this year. “People have been coming in twos and threes, and spending long hours at the bar. No one is rushing to grab drinks before heading to parties even on weekends.”

“There has definitely been a change in dining out habits, especially with regard to cocktails. I think the pandemic has made people more open to experimentation out of fear of missing out on life. More are looking for newer experiences in the form of signature cocktails, and are willing to pay more to find these.”Priyank SukhijaRestaurateur and barpreneur

Bucking the trend

As India’s drinking culture reaches a new but sophisticated high, it’s not surprising to read the global numbers and realise how the country is also bucking global trends.

The country is one of the fastest growing markets for different categories of alcoholic beverages, while the world over, some of the most developed rich markets have been showing a decline in alcohol consumption. Health concerns and shifting lifestyles have led to Gen Z drinking less than the millennials, who drink less than Gen X and the Baby Boomers. Signs of this cultural shift started surfacing in 2018, when an influential report by Berenberg Research found Gen Z in the U.S. were drinking 20% less per capita than millennials.

“I definitely drank more martinis in the early days of the pandemic shutdowns than ever before or ever after, but in general, consumption has been declining for years among millennial and Gen Z drinkers over health concerns. There’s data linking it to other things such as the decriminalisation of cannabis, too,” says New York-based Emily Saladino, culinary editor for Food Network.

It’s not just the U.S., one of the largest markets, that has been showing declining statistics. Markets such as Germany and Japan are drying off, too. In fact, last year the Japanese government launched ‘The Sake Viva!’ campaign, calling for ideas from those between 20 and 39 years to help promote alcoholic drinks!

India, on the other hand, has emerged stronger. A resilient economy — with rising consumer incomes, market recovery and growth post-pandemic — is a big reason. “As geopolitical and economic turbulence impacts the market, alcohol drinkers are shifting their consumption patterns,” notes Mark Meek, CEO, IWSR (International Wine & Spirits Record) Drinks Market Analysis.

According to IWSR 2022, the global benchmark for beverage alcohol data, India is now the number one market globally for whisky, rum and brandy. And while the global alcoholic beverage market is expected to grow at a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of around 1%-2% by volume and value in the next few years, the Indian market has a growth rate of 6.8%; up even more in premium plus segments such as that for whisky, where stats point to a whopping 61% growth. This rides on rising affluence, including in the smaller towns as the economy shows resilience, and customers trading up to better brands and new emerging luxury categories.

Gen Z and social drinking

Are younger Indians then drinking more than their global counterparts? Not necessarily. “It’s not as if people are drinking more,” says Smriti Sekhsaria, marketing head of Moët Hennessy India. “Younger consumers of legal drinking age are more prudent today about alcohol choices and respectful of boundaries. But more people are drinking.”

Liquor companies have projections mentioning the possible addition of 100 million new drinkers over the next five years as India’s young population matures. “One pivotal aspect contributing to India’s potential is its status as the youngest large economy globally,” points out Vikram Damodran, chief innovation officer at Diageo India. He adds that “codes of authenticity, individuality, local pride and collaboration” are important to the younger demographic, and drives choices and thus spends, not just in the metros but in smaller Tier II cities too, fuelled by rising affluence.

By 2030, 40% of all growth in alcoholic beverages will come from Asia-Middle East-Africa, as per IWSR 2022. And India leads the charge, along with some others in Asia such as Singapore, Dubai, Korea and Hong Kong, all tourism destinations. “For Bacardí, India is the no. 1 emerging market and more than half our growth in the Asia-Middle East-Africa region is derived from India,” says Zeenah Vilcassim, marketing director, Bacardí India.

“We have a lot of aged, luxury whiskies that we find whisky lovers in India enjoying, such as Glenmorangie Signet and our Grand Vintage expressions.” Bill LumsdenDirector of whisky creation at Glenmorangie

The craft advantage

Social media exposure through the pandemic has shortened the time for global trends to catch on in India. While the craft gin trend caught on here almost a decade after its start in the US — by 2017, when India’s first craft gin Greater Than was launched, big companies such as Pernod Ricard were already acquiring craft brands like Monkey 47 from Germany’s Black Forest area — today the lag is much shorter. “Within six to nine months of sipping tequila becoming a big trend in the U.S., it has already caught on in India with virtually no marketing push or launch,” says Sekhsaria.

People are drinking more premium beverages and are ready to pay more. There is occasion-led drinking (with newer “occasions”, such as lunch time with friends), experimentation with flavours and people switching alcohol choices depending on when and where they are drinking. “In India, till about eight or nine years ago, the favourite cocktail of high spenders was whisky with half water, half soda,” laughs restaurateur Rakshay Dhariwal. But no longer so. Incidentally, Dhariwal founded India’s first speakeasy PCO, which has been responsible in many ways for ushering in the present craft cocktails revolution.

Prepared from better alcohol, often with local ingredients, and showcasing international techniques such as the rotovap (a distillation technique used in perfumery), sous vide, milk clarifications, carbonation, clear ice programmes and more, craft cocktails has put India’s drinking culture in league with other thriving, evolved centres of mixology in Asia such as Hong Kong and Singapore. But with its own uniqueness.

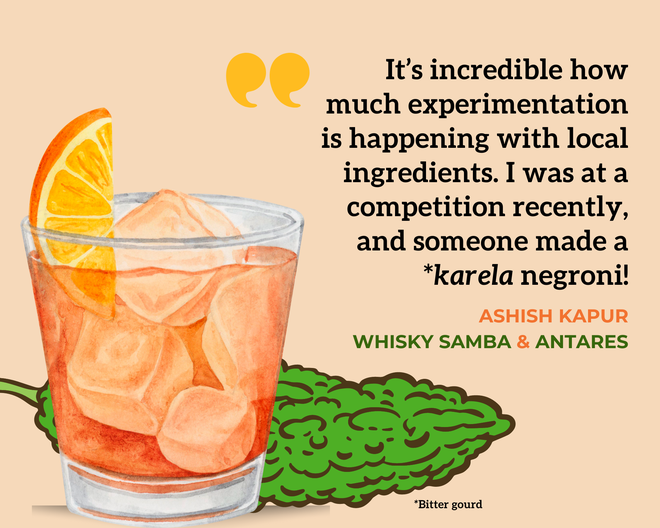

If the use of bitters and complex liqueurs mark craft cocktails in Europe, America and other parts of the world, India with its diversity of spices, fruit, flowers and vegetables is a “playground from any one who wants to work with flavours”, states Maxim Schulte of The Herball, a drinks formulation and consultancy in London, who headed the American Bar at the Savoy. Schulte was in Mumbai earlier this year for a residency at the restaurant Noon and went foraging for ingredients such as mahua flowers, niger seeds, karonda, wild mango, and agar wood in the interiors of Maharashtra and used all these in his minimalist drinks.

Young Indian bartenders, of course, have been quick to seize this advantage. “Indian bartenders have the best palates since we are used to complex flavours in our food,” says Ranveer Kumar, 33, who heads the bar at Wolf, a new speciality bar in Delhi. It is a sentiment recognised by many, including by top international bartenders like Schulte. “So, once we learn the techniques, Indian bar talent finds many opportunities, including internationally,” Kumar adds.

Rise of the small town bartender

Booming bars with their glamorous lifestyle and scope for rapid advancement are a magnet for many from the smaller towns. With the small clutch of India’s top bartenders — Lama, Pankaj Balachandran and Arijit Bose, who currently run the consultancy Countertopindia, and Nitin Tewari, who also consults — now elevated to celebrity status (thanks to social media and India’s evolving cocktail culture), younger bartenders see them as role models. The seniors, in turn, have been mentoring upcoming talent via workshops, master classes both in schools and labs that they have set up, and at various events and online sessions.

Kumar of Wolf shares how mentorship has helped evolve the bar culture in India and equipped thousands of small town boys and girls to find well paying work in the cities. He himself hails from a teetotaller Brahmin family in Begusarai, Bihar, and used to sell flavoured shaved ice at a kiosk before studying bartending at Lama’s Cocktails and Dreams.

“A lot of young boys look up to them [senior bartenders] and see them as role models,” says Sahil Negi, 28, from Pauri Garhwal, who has been mentored by Balachandran and works at Perch Delhi. “It’s a skilful job and if you do it well, there is a lot of scope for rising quite quickly in the field and Indian bartenders are in demand not just in India but internationally too in Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai post pandemic,” he says. The alcobev industry in India, according to the ICRIER (Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations) report on the sector in 2021 contributes to around 15 lakh jobs nationally.

In fact, the bartender is the new celeb chef in India. “Today, there is no difference between the respect a bartender and a chef gets. Even in terms of salaries, I would pay the same to a top chef and a top bar lead depending on whether the format is food or drinks led,” says Dhariwal.

Navigating state policies

Brand push and marketing spends

In the last four-five years, there have been several fashion, art, food extravaganzas accompanied by curated spirited evenings, cocktail weeks and bar takeovers by vaunted foreign hands. Think Bacardí’s Rum Room or bar takeovers by Mexico’s Hanky Panky in Bengaluru and Delhi, brought in by Moët Hennessy. While it is not clear how much of an effect these have on buying decisions or revenues of bars, indirectly these marketing activities have been growing India’s drinking culture and putting it on the world map.

There are clearly big marketing spends being invested in the Indian market. Festivals such as The India Cocktail Week — which came up in 2019 in Delhi and is now an annual event, across multiple cities — has an estimated budget of ₹3 crore. This is more than the capital expenditure for an average small bar, which may require almost ₹1 crore to set up, depending on location. Approximately 10,000 people have been coming to the bigger editions and the fest is profitable. Revenue, says Dhariwal, the architect of the festival, comes from stall, drink sales and tickets. All the major brands participate and contribute by way of stocks, hosting sessions, as well as the cost of space where they put up stalls.

All across India, there are hundreds of smaller marketing initiatives, including the currently popular bar takeovers by top foreign bartenders. These are brought in by brands, who also facilitate exchange programmes with Indian bartenders doing guest shifts at big bars internationally. This has created a culture where Indian talent is finding global exposure.

“The brands have been supporting us with travel, stocks and arrangements when we do guest shifts internationally,” says bartender Sahil Negi, who has visited London, Singapore, Hong Kong and Thailand in the last two-three years much to the envy of his friends back home in Pauri Garhwal. “Apart from the glamour of this lifestyle, this exposure also helps us hone our skills and develops us personally,” he adds.

Talk to anyone in the beverages space and you will know how the last three four years have seen the entire industry come together — brands and companies, bartenders, influencers and barprenuers. “Earlier everyone worked in silos, but now if a foreign bartender comes to do a guest shift at one bar, the owners will take that team to [visit] all the good bars in the city instead of seeing them as rivals. Everyone is now thinking in terms of how to get global exposure for India’s bar culture and acclaim for the talent here,” concludes Balachandran.

The writer is the author of Business on a Platter.