For as long as there has been an international anime fandom, there has been a debate over the merits of subs vs. dubs, with the latter historically regarded as the inferior option by hardcore fans. Not by legend Hayao Miayazki, however. In a 2005 interview with The Guardian around the release of Howl’s Moving Castle, the Japanese animation auteur refused to rank the two localization formats, saying: “When you watch the subtitled version, you are probably missing just as many things. There is a layer and a nuance you’re not going to get. Film crosses so many borders these days. Of course it is going to be distorted.” In other words: Back off, dubs haters.

I may be taking some liberties with my interpretation there, but I think it’s fair to say that Hayao Miyazaki is not interested in engaging in The Great Subs vs. Dubs Fan War. Rather than look down on dubbing as a localization format, from the proper start of Studio Ghibli films’ entrance into the English-language market, Miyazaki has taken every pain to make sure his creative vision is as accessible as possible to interested viewers who don’t speak Japanese and who do speak English. (I cannot speak to the quality of Miyazaki dubs in other languages.) This doesn’t mean no dubs; it means good dubs, and it’s a distinction that has been instrumental to Miyazaki’s success in the United States.

While Joon-ho Bong may have famously made a plug for overcoming the “one-inch barrier,” it’s still considered an ask for adult viewers fluent in English to read subtitles. It’s notable that, for a breakaway foreign-language hit like Squid Game, roughly 60 percent of viewers in the U.S. watched the dub. Anime dubs have gotten better since the ’90s, but Miyazaki has always demanded a high level of quality from the English-language dubs of his classic films, a distinction that has allowed for broader access — both critically and commercially — to his work.

When Kiki’s Delivery Service was released on video in the U.S. in 1997, its English-language voice cast included recognizable names like Kirsten Dunst, Debbie Reynolds, and Lawrence brother Matthew. The multigenerational name recognition of the voice cast gave the film multiple entry points across a family. More broadly, high-quality dubs continue to make Miyazaki’s films more accessible to children who have not yet learned how to read fluently. This “family film” status, though not applicable to all of Miyazaki’s films with more mature themes, cannot be discounted as a factor in the rise and continued popularity of Studio Ghibli. Disney seemingly invested even more in the English-language voice cast for Princess Mononoke, which was the first Ghibli film to be released in U.S. theaters under the deal. Its voice cast included Claire Danes, Gillian Anderson, Minnie Driver, and Billy Bob Thornton, not to mention an English-language script penned by Neil Gaiman.

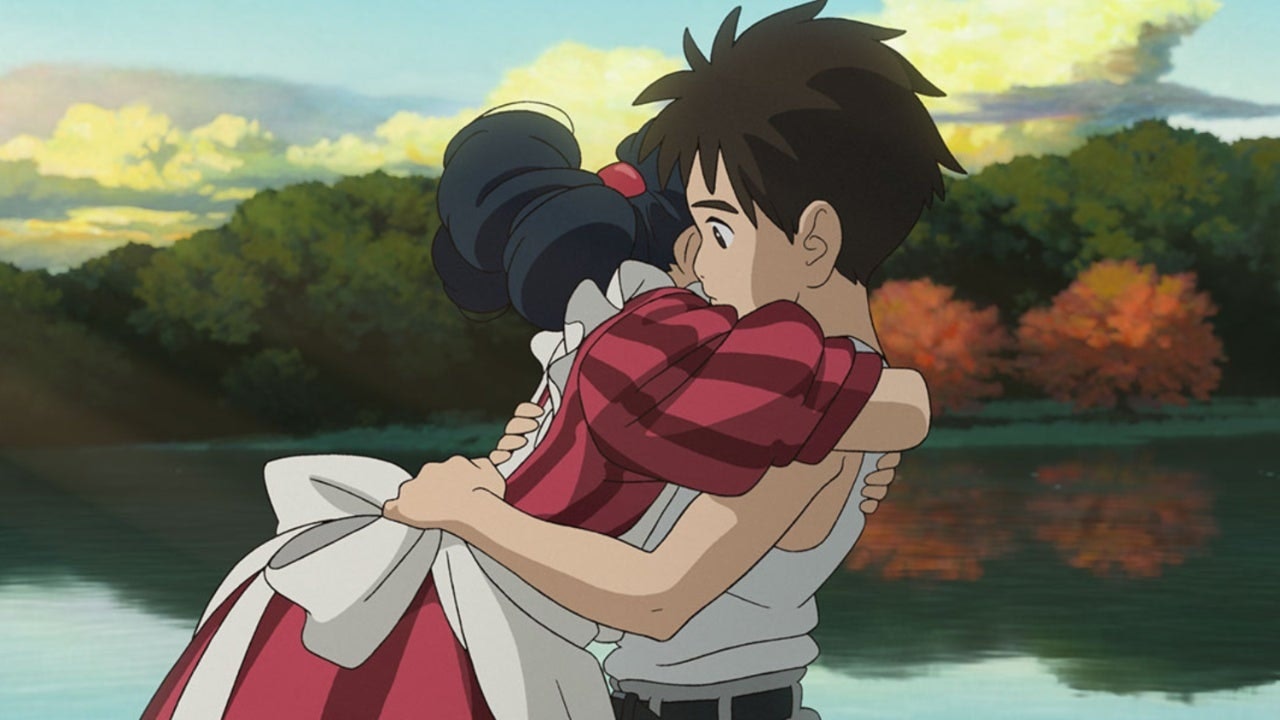

Over the years, the English-language voice casts for other Miyazaki films have included Academy Award winners Christian Bale and Cate Blanchett, American pop culture icons like Keanu Reeves and Mark Hamill, and the Sir Patrick Stewart. Miyazaki’s latest, The Boy and the Heron, boasts the return of Christian Bale, as well as other big-name movie stars like Robert Pattinson and Florence Pugh lending their voice for the fantastical feature.

It’s not just that Miyazaki, and other Studio Ghibli, films attract top-tier acting talent; they also give them the space to do their craft. In a behind-the-scenes featurette about the English-language voice recording process for The Wind Rises, actors including Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Stanley Tucci, and Emily Blunt rhapsodize over the complexities of the story and their respective characters within it. Yes, part of their job is to market the film through promotional materials like this featurette, but it’s clear in the clips showing the actual recording process just how good they are at their jobs and just how much care they are putting into their performances. In this case, the process is helmed by voice director Gary Rydstrom, who has won seven Academy Awards for his work in sound, including for Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, and Titanic. “Our first job is to stay true to what the movie is, to the characters, and to the script of the original movie,” says Rydstrom in the featurette, seeming nothing but honored to be helping to preserve Miyazaki’s vision.

But it’s more than just the voice talent that has preserved the quality of Miyazaki’s films — the director has taken an active part himself in keeping the Western releases of his films as true to the original as possible. Miyazaki was famously so dissatisfied by an English-language dubbed release of his 1984 film Nausicaä: Valley of the Wind that he developed a “no-cuts” policy for the international distribution of his films moving forward. This would come into play in 1996, when Studio Ghibli signed a distribution deal with Disney. When Harvey Weinstein tried to edit Princess Mononoke for its 1999 release in America, Studio Ghibli co-founder Toshio Suzuki famously sent him a katana with a note reading: “No cuts.”

While it’s interesting to ask the question “Why are Miyazaki dubs so good?,” it’s also helpful to ask the question “Why are so many anime dubs so bad?” And to know that it’s, in no small part, because doing a good dub is hard. It takes time, and it takes resources that many distributors — especially in the earlier days of international anime fandom — simply didn’t have. “The actors on these types of projects have a really tough job,” Rydstrom says. “They have to match, sync, and act. And it’s really hard.”

It’s a gift to have a creator like Miyazaki, who has not only always seemed to understand that reality of dubbing, but has never judged the format by its worst examples. Instead, he has used his power to support the undervalued creative process, showcasing all that is possible when dubs are given the resources to succeed.