When Zougba’s husband fled the jihadist violence crippling Burkina Faso, she soon found herself with her young son, daughter and other women on the road in a mission to join him. After 10km, four armed men surged into view from the side of the road. Her children bore witness as the men raped her, one after another. The police arrived too late.

More than 40% of women in West Africa are victims of violence at least once in their lifetimes, according to a 2018 report, Réseau des Femmes Elues Locales d’Afrique (REFELA). Together with Central Africa (65% of women are victims of violence), these two regions constitute the part of the world with the highest level of violence against women (REFELA 2018 report).

To better identify the extent of such violence, particularly sexual violence, its variation by age and the main perpetrators involved, here we present some indicators. The countries covered are Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Gambia and Togo. Data was obtained from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), compiled with the view of determining the types of violence women have experienced, the age at which the violence began, its frequency as well as its perpetrators. We incorporate victims’ testimonials from the GBV West Africa Exposed website to put faces on what could otherwise be anonymous numbers.

In search of reliable data

The major challenge in measuring indicators of violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa, and particularly in West Africa, lies in the lack of reliable data.

The reasons are similar to other parts of the world: poor reporting facilities, a persistent culture of victim-blaming and a heavy taboo surrounding sexual abuse. African countries also suffer from imperfect statistical and demographic data system, making what is visible only the tip of the iceberg.

In recent years, the DHS have attempted to gather data to capture the full spectrum of domestic violence in developing countries. Although they generally cover only women of childbearing age (15-49), they produce results that are nationally representative and comparable across countries. However, indicators of violence against women obtained from DHS are not exhaustive across countries.

How prevalent is physical and sexual violence in West Africa?

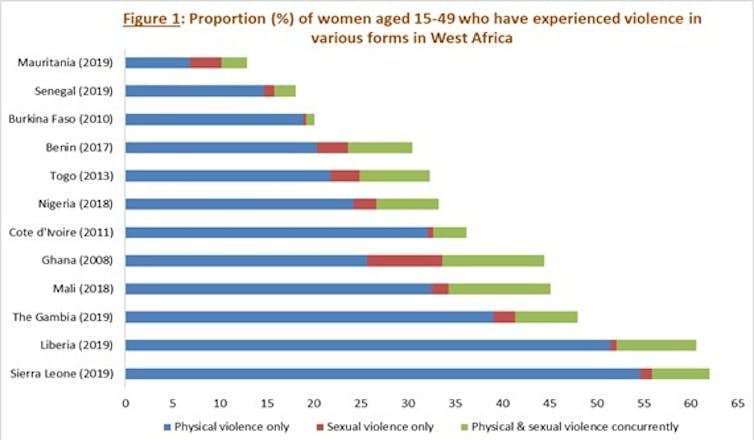

As shown in Figure 1, above, some surveys, such as the DHS, calculate indicators that distinguish between strictly physical violence, strictly sexual violence, and violence that is both sexual and physical. But this last category is added to each of the previous two when we are specifically interested in sexual violence or physical violence.

The proportion (%) of women who have experienced at least one act of physical or sexual violence in their life is very high in West Africa. In certain countries, this amounts to more than twice the global average) (27%) and six times higher than the European average (10%).

We nevertheless observe variations between countries. While it is relatively low in Mauritania (12.9%), Senegal (18.1%) and Burkina Faso (20.1%), it exceeds 60% in Liberia and Sierra Leone (60.6% and 62%, respectively). The figures for Liberia and Sierra Leone certainly reflect a legacy of civil wars in which physical and sexual violence against women (particularly rape) was deployed as a weapon.

The remainder of statistics sees Benin at 30.5%; Togo, 32.3%; Nigeria, 33.4%; Côte d’Ivoire, 36.2%; Ghana 44.5%, Mali, 45.1%, and Gambia, 48%. If we are to go by the numbers, acts of physical violence outnumber ones of sexual abuse by about three to one.

Rates and trends of sexual violence

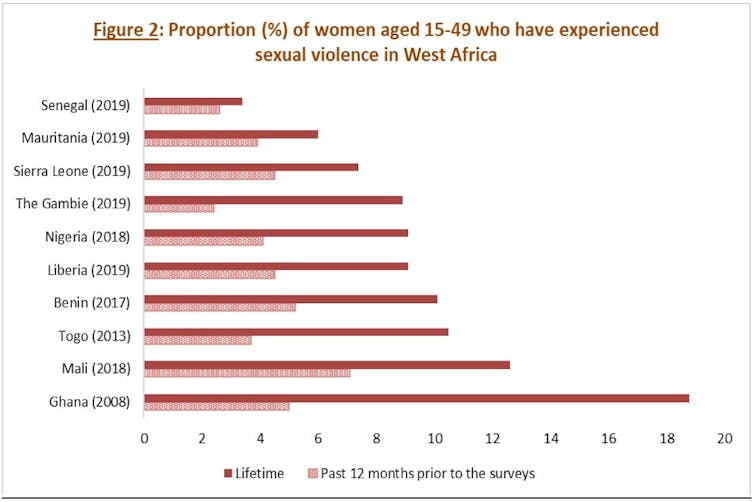

Figure 2 presents the proportions (%) of West African women who have experienced acts of sexual violence in the 12 months preceding each survey. These included rape, sexual assault and any other act of a sexual nature without consent.

The figure looks at sexual violence framed as having been only sexual and concurrent with acts of physical violence. On average, 10% of women reported having experienced sexual violence in their lifetime, and 4% in the 12 months before the survey.

Ghana has the highest lifetime sexual violence experienced by women (19%) compared to a lower level in Senegal (3.4%). Benin, Togo and Mali have lower levels than Ghana but exceed 10% (10.1, 10.5 and 12.6, respectively). Gambia, Liberia and Nigeria all score 9%, while Sierra Leone is at 7.4% and Mauritania, 6%.

The relatively low prevalence of violence against women in Senegal can be explained by the country’s considerable progress in gender policy in recent years. For example, it is the region’s only country to have equipped every one of its ministries with a gender unit, while locally elected “agony aunt” figures, known as the Bajenu Gox, watch over their communities in a bid to prevent gender-based violence. It has undoubtedly benefited from an influx of international organisations dedicated to promoting women’s rights.

In terms of trends, the proportion of women who report having experienced sexual violence in their lifetime has tripled in Mali (4% in 2006 and 12.6% in 2018), doubled in Gambia (4.6% in 2013 and 9% in 2019) and shot up by 30% in Nigeria (7% in 2008 and 9.1% in 2018). In contrast, it was divided by 2.5 in Senegal (8.4% in 2017 and 3.4% in 2019), by 1.4 in Sierra Leone (10.5% in 2013 and 7.4% in 2019) and almost by 2 in Liberia (17.6% in 2007 and 9.1% in 2019).

The increase in sexual violence in some countries in the region (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso) is linked to the security crisis in the Sahel and its many terrorist attacks. In that regard, the story of Sadia – a 28-year-old Malian woman, who was abducted by an armed group, detained for 19 days and raped – is not uncommon. Nor is that of Ariette, a 17-year old in Burkina Faso who was forced into marrying a 65-year-old trader who hits and rapes her every night.

First acts of sexual violence at very young ages

“He was the son of my uncle’s friend whom I knew and considered my family. And yet when I was 14, he defiled me; he raped me. The pain of this rape had not finished consuming me until I found out that I was pregnant by this man.” (Lucy, Senegal)

Age is an essential factor in sexual violence in West Africa. Many, like Lucy, experience their first acts of sexual violence when they’re very young. Almost everywhere in the region, more than 60% of female victims of sexual violence report having experienced the first acts of such violence before the age of 21 (74% in Gambia, 71% in Mali and Ghana, 70% in Liberia, 67% in Nigeria, 65% in Togo, 62% in Benin and Sierra Leone, 35% in Mauritania and 12% in Senegal) (Figures 3a and 3b).

Gambia, Liberia and Sierra Leone have the highest proportion of women who first experienced sexual violence at a very early age (before age 15) (34%, 29% and 22%, respectively). The figures are around 18% in Nigeria, 16% in Benin and 13% in Togo, Mali and Ghana, respectively. In Senegal and Mauritania, on the other hand, this precocity is less pronounced (3% and 8%, respectively).

Violence is mainly committed by intimate partners

The vast majority (more than 80%) of sexual violence against women in West Africa takes place within couples. On average, nearly 60% of victims named the husband or current spouse as the perpetrator (80.5% in Mali, 78.7% in Senegal, 69.1% in Sierra Leone, 68% in Mauritania, 61.5% in Benin, 53% in Nigeria, 44% in Togo, 43.8% in Liberia and 37.8% in Gambia). Nearly 16% of victims named a former husband or spouse (24% in Liberia; 21% in Togo and Gambia; 17% in Mauritania, Benin and Sierra Leone; 15% in Nigeria; 11% in Ghana, 10% in Senegal and 5% in Mali) while 10% of victims named a former or current boyfriend (30% in Ghana; 14% in Liberia; 10% in Nigeria; 8% in Liberia; 7% in Sierra Leone, Benin and Togo; 6% in Mali and 4% in Senegal).

To a much a lesser extent, other perpetrators of sexual violence reported by women in West Africa also include relatives, friends, acquaintances or strangers.

High rates of teenage marriage and motherhood

A traditionally entrenched feature of West African societies, teenage motherhood continues to blight communities despite shifting fertility behaviours and attitudes toward the family.

In part, this explains why women in West Africa are more likely to suffer from sexual violence at a young age and at the hands of intimate partners. Ariette, mentioned above, is one example out of thousands of an early and forced union that turned violent.

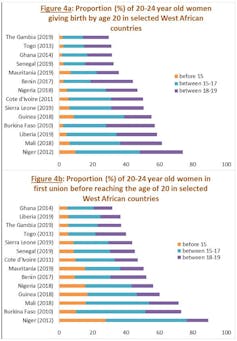

The percentage of women who have had a child before age 20 is very high (47% on average), even among recent young cohorts (Figure 4a). This situation goes hand in hand with the early age of the first union. For example, among women aged 20-24 during the 2010-2020 decade in West Africa, 52% entered their first union before age 20, with a low of 32% in Ghana and a high of 89% in Niger (Figure 4b).

Domestic violence among first-time teenage mothers

The link between the two phenomena deserves further scientific investigation in the context of frequent teenage motherhood and early domestic (especially sexual) violence. In situations like those in sub-Saharan Africa, where the transmission of family values is rooted in a strong hierarchy, the violence against teenage mothers can be perpetuated across generations.

But the persistence of social norms of early fertility within a union may clash with individual aspirations to freely control fertility choices. This collision can exacerbate levels of violence, particularly in the early years of childbearing.

To better analyse these implications, we are developing the EarlyFertiViolence project (Early Fertility, Marital Status and Domestic Violence During First Motherhood in West African Countries: Trends, Convergence, Divergence and Associated Factors), which is scheduled to begin in 2023, involving research labs and researchers at Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne University and the University of Chicago.

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.