Mick Jagger was at a birthday party for Eric Clapton when Mick Taylor leaned over and told him he was leaving the Rolling Stones. It was 12 December 1974 and Jagger, Taylor and assembled guests were watching a fireworks display. “Do you think he was serious?” a bereft Jagger asked Ronnie Wood who was standing nearby.

Taylor was deadly serious and this was a decision that had been a long time in the making. In the 2012 documentary Crossfire Hurricane, Taylor said he was addicted to heroin and left to try and protect himself and his family from the maelstrom of being a member of the Rolling Stones.

The issue of songwriting credits was also mentioned by Taylor in an interview with Mojo in 1997. "We used to fight and argue all the time. And one of the things I got angry about was that Mick had promised to give me some credit for some of the songs – and he didn't. I believed I'd contributed enough. Let's put it this way – without my contribution those songs would not have existed. There's not many but enough, things like Sway and Moonlight Mile on Sticky Fingers and a couple of others."

In his 1995 interview with Rolling Stone, Jagger said he felt that friction between Taylor and Keith Richards was also a contributing factor: “I think he found it difficult to get on with Keith."

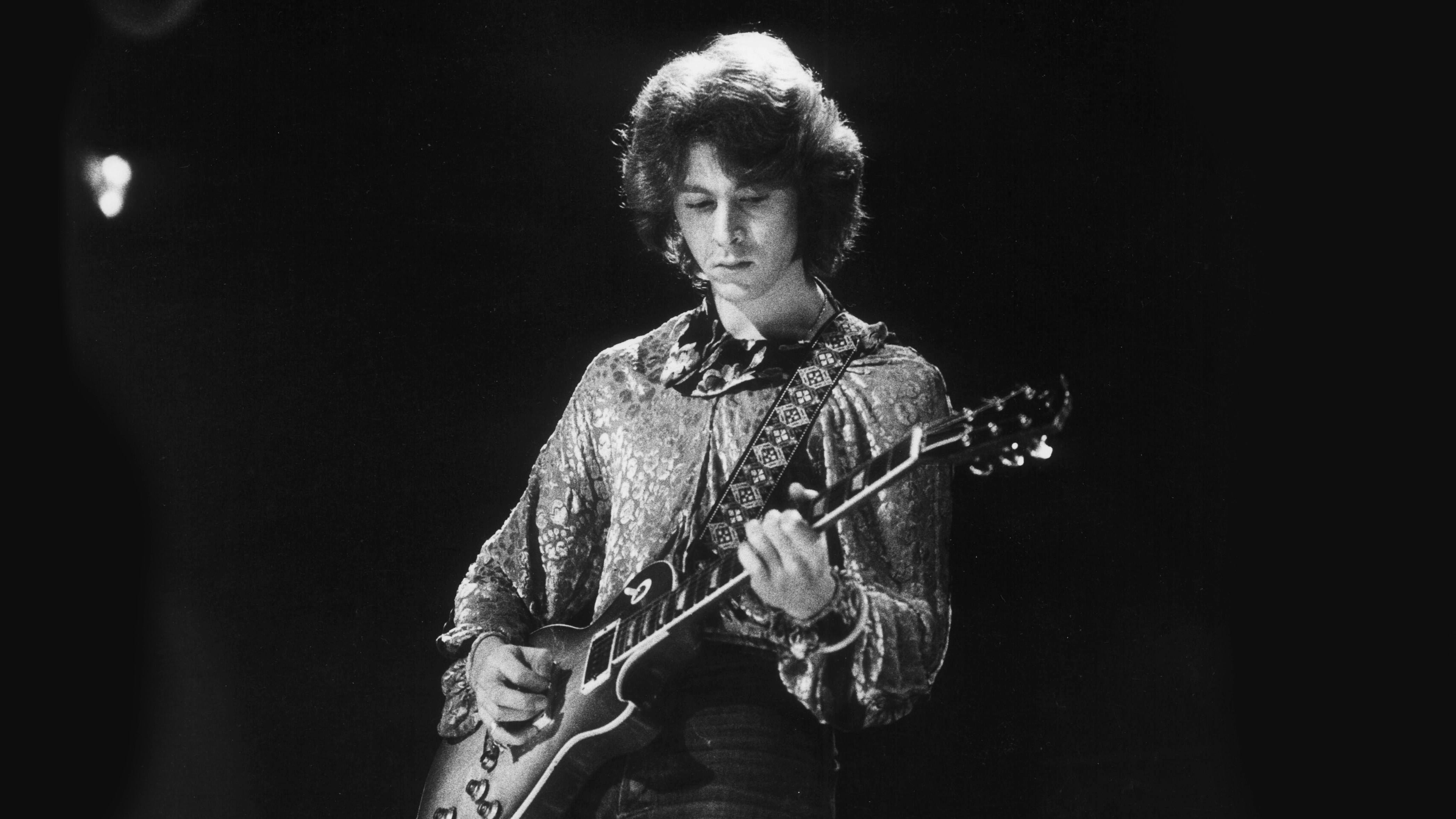

Whatever the reason, the reality was that the Stones were losing a mercurially talented player. For all their combined talents, Taylor was a virtuoso, whose stunningly fluid and emotive playing elevated the Stones to new heights. Just as the band was transformed when he joined its ranks, it was equally transformed when he left – a testament to his peerless and prodigious talent.

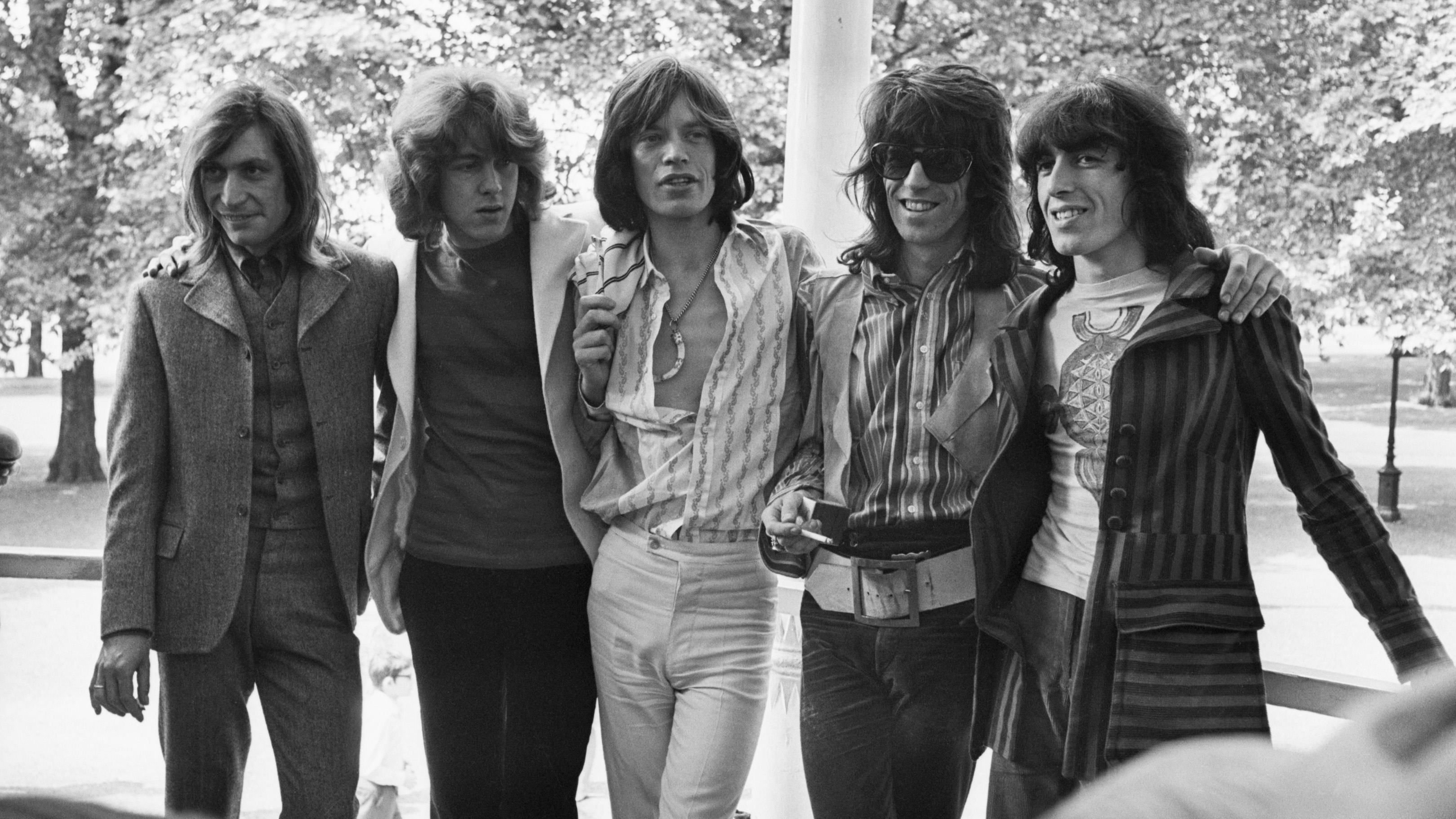

For Taylor, who joined the band following the death of Brian Jones in 1969, stepping into a band of the scale of the Stones was a shock. He was just 20 and much younger than the rest of the Stones when he made his baptism-of-fire live debut at their free concert in Hyde Park, on 5 July 1969, in front of 250,000 people. This was just two days after Brian Jones had been found dead in his swimming pool, after being fired from the band almost a month earlier.

It was revered British blues purist John Mayall who recommended Mick Taylor to Jagger. In April 1966, Mayall had asked Taylor to join his band the Bluesbreakers, replacing the departing Peter Green, who in turn had replaced Eric Clapton.

When Jagger and Richards invited Taylor along to Olympic Studios he was reportedly shocked by how under-rehearsed the Stones were. At that point, he thought he was simply there to play a session.

He was invited back the next day to continue rehearsing with the band, who were recording their eighth studio album, Let It Bleed. Taylor ended up overdubbing guitar on the tracks Country Honk and Live With Me, as well as the single Honky Tonk Women.

Jagger and Richards were blown away by the youngster’s playing and invited him to join the band. Mick Taylor would go on to play on five Rolling Stones studio albums: Let It Bleed (1969), Sticky Fingers (1971), Exile On Main Street (1972), Goat's Head Soup (1973), and It's Only Rock And Roll (1974). His stellar playing is also captured on the live 1969 album Get Yer Ya Yas out, recorded over four nights at New York’s Madison Square Gardens.

He was a very fluent melodic player, which we never had and we don’t have now

Mick Jagger

Mick Taylor’s playing would bring fluidity, spontaneity and excitement to the Stones. He was able to contribute a level of virtuosity that the Stones had not had before. Taylor re-energised the Stones and his tenure with the band would be defined by many as the golden era of the Stones’ recorded output. It was a view reinforced by Jagger.

“I think he had a big contribution,” Jagger told Rolling Stone magazine in 1995. “He made it very musical. He was a very fluent melodic player, which we never had and we don’t have now. Neither Keith nor Ronnie Wood plays that sort of style. It was very good for me working with him. I could sit down with Mick Taylor and he would play very fluid lines beneath my vocals. He was exciting, and he was very pretty, and it gave me something to follow, to bang off. Some people think that's the best version of the band that existed."

Live With Me was the first track Taylor played on as they put the finishing touches to Let It Bleed. His influence is immediate on this pacey song with its Stax-style 4/4 attack. On Honky Tonk Women, he reels off sultry and slinky blues lines that fit seamlessly within Richard’s groove-laden chops.

But it was on the Stones 1969 US tour, from 7 November to 6 December, where Taylor really started to make his mark and his playing can be heard on the band’s live album Get Yer Ya Yas Out (1969). Like Peter Green, there is a real melodicism to Taylor’s playing, with memorable motifs woven within expressive freeform playing. Taylor is also a mean slide player, as is evident on Love In Vain.

On the pacey, infectious shuffle of Midnight Rambler, Taylor reels off searing lines on his ‘58 Sunburst Les Paul. On the outro of Sympathy For The Devil, he injects real groove and attack, powering the song forward with searing lead.

Listening to this album now, it’s striking how powerful and unbridled the Stones sound, and the calibre of Taylor’s guitar work is a key element of that renewed energy. As Keith Richards notes in his book Life, “Mick Taylor being in the band on that ‘69 tour certainly sealed the Stones together again”.

By 1969, the Rolling Stones had morphed into a rock band, but their mid-60s pop sensibilities still exerted a hold in terms of arrangement and structure. Mick Taylor helped change all that, bringing jazz sensibilities and a much looser, more adventurous feel.

Creatively, Taylor’s first real studio contribution was Sticky Fingers (1971). Keith Richards recalled Taylor’s contribution to that album in his 2010 autobiography Life. “So we did Sticky Fingers with him. And the music changed – almost unconsciously… You write with Mick Taylor in mind, maybe without realising it, knowing he can come up with something different. You’ve got to give him something he’ll really enjoy. Not just the same old grind.”

It’s an album that blends blues, country and Southern soul, and is brimming with Taylor highlights. There’s a real swagger to his lead playing on the track Sway while his country licks on Dead Flowers are impeccable. But it’s the song Can’t You Hear Me Knocking, that is arguably the album’s centrepiece and the perfect showcase for Mick Taylor’s supple talents.

“Can’t You Hear Me Knocking came out flying,” recalled Keith Richards in his 2010 autobiography Life. “We’re thinking, ‘Hey, this is some groove’.”

You write with Mick Taylor in mind, maybe without realising it, knowing he can come up with something different

Keith Richards

The real highlight is the track’s extended jam, which takes the song from its original length of 2:43 to 7:14. This was a happy accident. After the supposed conclusion, the band kept playing and the tape kept rolling, capturing masterful playing from Taylor, who starts picking out a repetitive Latin-flavoured motif on his walnut brown Gibson ES-345 through a Ampeg VT-22 amp.

“Towards the end of the song, I just felt like carrying on playing,” says Taylor on the UDiscoverMusic website. “It sounded good, so everybody quickly picked up their instruments again and carried on playing. It just happened.”

It’s a majestic, improvised solo with a Santana-like feel, that dips and dives between strident phrasing and beautifully judged melodicism. At 6:02 he veers into a raunchy repetitive pattern, which Charlie Watts and the horn section spontaneously accentuate with pushes.

“Generally, I tried to bring my own distinctive sound and style to Sticky Fingers and I like to think I added some extra spice,” said Taylor. “I don’t want to say ‘sophistication’ – I think that sounds pretentious. Charlie said I brought ‘finesse’. That’s a better word. I’ll go with what Charlie said.”

Taylor’s skills are slightly more diminished on the stunning follow-up album Exile On Main Street, recorded at Nellcôte, the villa leased by Keith Richards during the band’s self-imposed tax exile on the French Riviera. It was during the recording of this album that he became hooked on heroin. But he continued to deliver some stellar performances, most noticeably on his stunning solo on Shine A Light.

Nellcôte rapidly became an epicentre for 24-hour hedonism. Chaos prevailed. Jagger then took the finished tapes to engineer and producer Glyn Johns to mix at Basing Street studios in London. In a 2015 interview in Mojo magazine, Johns recalled working on a track on which Mick Taylor had recorded backing vocals, drums and bass. When Taylor asked Johns why he had removed them Johns replied “The Rolling Stones have a f**king great drummer and a really great bass player. You, sunshine, play the guitar and you’ll hear it rather nicely when I’ve finished this.”

The Stones received some criticism for next album Goat’s Head Soup, which was recorded in Jamaica, although Billboard magazine praised Taylor for his “superb guitar work” on the album.

I think it’s probably the best thing I did with the Stones

He continued to excel on his final album with the band, It’s Only Rock And Roll. Taylor’s favourite personal moment in the Stones occurred during the recording of the track Time Waits For Noone. “I love that solo,” Taylor told Damien Fanelli of Guitar World in May, 2012. “I think it’s probably the best thing I did with the Stones. It’s not one of their hits; it was an album track. But it’s quite lyrical and it’s a bit different from a lot of other Stones songs. I’d done something that I’d never done. Because of the structure of the song, it pushed my guitar playing in a slightly different direction.”

In his autobiography Life, Keith Richards confesses to having sometimes been in awe of Taylor’s playing, citing his “the melodic touch, a beautiful sustain and a way of reading a song” but he also says Taylor was “very distant”.

For the Riolling Stones, Mick Taylor’s departure in 1974 left a significant void as they mulled over an array of possible contenders, such as Ry Cooder, Rory Gallagher, to replace his blues-infused virtuosity. In the end they didn’t try to replicate what Taylor had but opted instead for a whole different style and personality with Ronnie Wood.

Twenty-four years on, in the 1998 book The Rolling Stones: A Life On The Road, Charlie Watts shared his thoughts on Mick Taylor’s contribution to the Stones. "I think we chose the right man for the job at that time just as Ronnie was the right man for the job later on,” he observed. “I still think Mick is great. I haven't heard or seen him play in a few years. But certainly what came out of playing with him are musically some of the best things we've ever done."