We were being sold Apocalypse Now. Saddam Hussein had a secret chemical and biological weapons programme. He was within months of testing a nuclear device. The threat was clear, present and imminent.

Iraq’s dictator, we were told, was intent on using his weapons of mass destruction. His forces were able to deploy them “within 45 minutes of an order to do so” using “an extensive range of artillery shells, free-fall bombs, sprayers and ballistic missiles”. British lives were at stake with military bases in Cyprus within range.

The prime minister, Tony Blair, spelt this out succinctly: “Saddam has existing and active military plans for the use of chemical and biological weapons, which could be activated within 45 minutes and he is actively trying to acquire nuclear weapons capability.” In another speech, he went into granular and scary details: “The biological agents we believe Iraq can produce include anthrax, botulinum toxin, aflatoxin and ricin. All eventually result in excruciatingly painful death.”

The British prime minister was echoing George W Bush across the Atlantic. “The people of the United States and our friends and allies will not live at the mercy of an outlaw regime that threatens the peace with weapons of mass murder,” vowed the US president. “The dictator of Iraq and his weapons of mass destruction are a threat to the security of free nations... the Iraqi regime is a threat of unique urgency. There’s a grave threat in Iraq: there just is.”

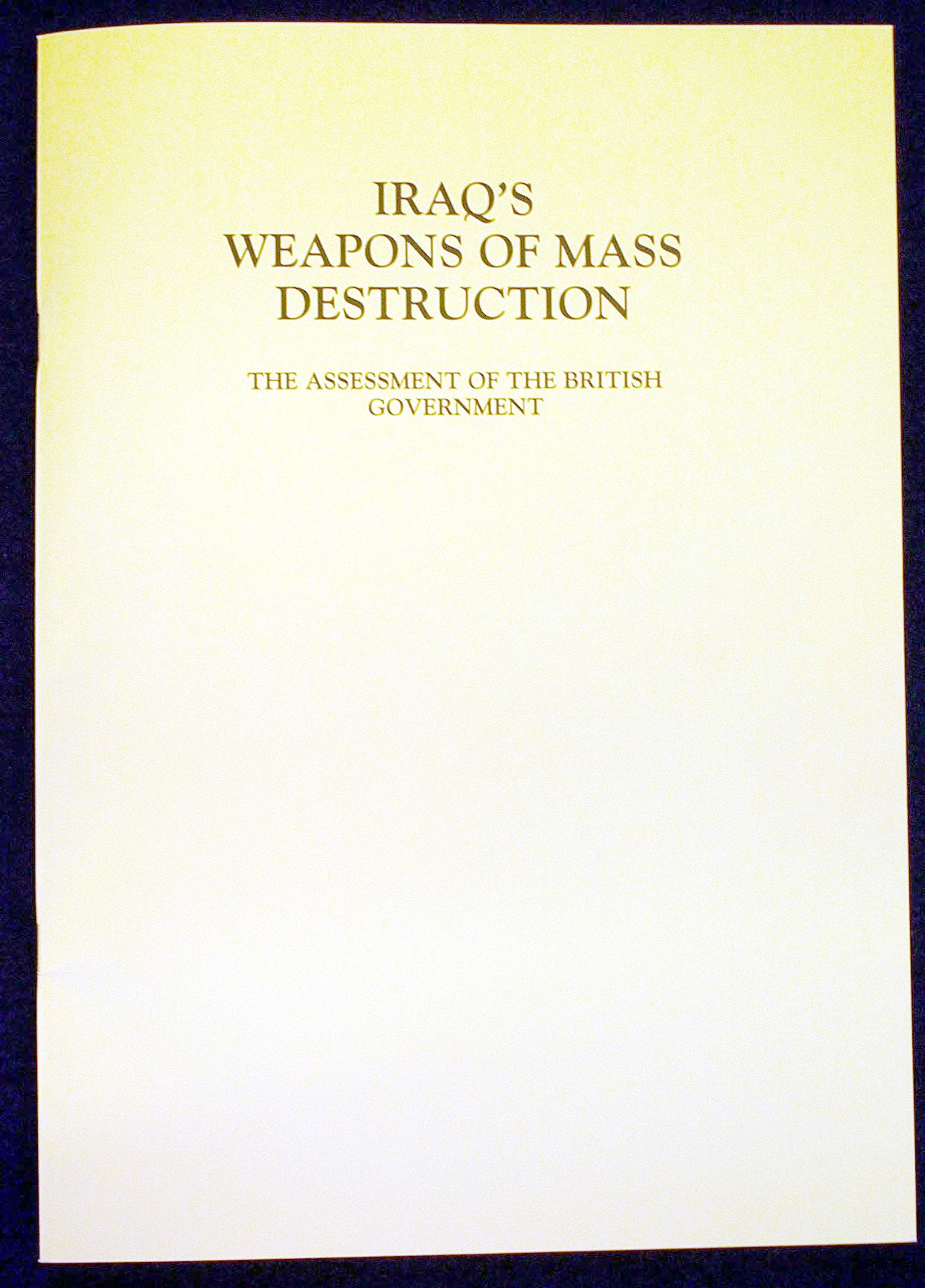

Both governments presented evidence to back up these claims in a dossier published on 24 September 2002. It was based on the conclusions of the UK’s Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) and the foreword was written by Blair himself. As well as the WMD and 45 minutes claims, the document revealed Iraq was seeking “significant quantities of uranium from Africa”, which could be enriched and used in nuclear weapons.

A second dossier was produced on 3 February 2003 and given to journalists by Alastair Campbell, Blair’s director of communications and strategy. This became commonly known as the “Iraq dossier”, later as the “dodgy dossier”. This one, with the title “Iraq – Its Infrastructure of Concealment, Deception and Intimidation” went into ever greater detail about Iraq’s WMD. Washington and London vowed they would not allow Saddam’s regime to have its evil way.

As the clock of war kept ticking down, a signal moment came with a presentation to the UN Security Council by Colin Powell on 5 February 2003. This was a dire warning being voiced by a distinguished and admired former general, not just some time-serving politician. Holding up a vial for dramatic effect, the US secretary of state declared: “My colleagues, every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are no assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.”

Except, as it turned out, none of it was based on solid intelligence; without exception, every single major claim made about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction fell apart in the months to come. The reasons given to justify war turned out to be false. At best, the “evidence” turned out to be “sexed up”, at worst it was fake – the product of plagiarising material without verification.

The fact-finding mission of scientists and weapons specialists sent in by the US and UK governments following occupation, the Iraq Survey Group, found – after extensive searches – no evidence of the weapons of mass destruction Bush and Blair were so emphatic posed a cataclysmic danger.

The claim of yellowcake uranium from Niger was based on a fake document, as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) quickly established when they were at last supplied it by the US. Some of the forgery was blatant, such as a letter dated 10 October 2000, supposedly signed by Allele Habibou as Niger’s foreign minister: Habibou had, in fact, left the job in 1989. “It was not really very difficult for us to come to the quick conclusion that these documents were forgeries,” pointed out Mohamed ElBaradei, the head of IAEA.

The “dodgy dossier”, which had been compiled by a group of civil servants under Campbell, had been plagiarised from various unattributed sources including a thesis by a student, Ibrahim al-Marashi, at California State University. Whole sections of his writing had been copied verbatim, including typographical errors. The language had been “toughened up” in other sections, in one instance the assertion that Iraq was “aiding opposition groups in hostile regimes” was changed to “aiding terrorist organisations in hostile regimes”.

A Commons foreign affairs committee inquiry into the Iraq war later concluded that this dossier’s publication was “almost wholly counterproductive” and only served to further undermine the credibility of the government’s case. The contents of this dossier became hugely controversial and the fallout played a key part in the accusations and recriminations that surrounded the death of Dr David Kelly, a weapons expert who had spoken to the BBC journalist Andrew Gilligan.

The September dossier also came under deep scrutiny in the various inquiries that followed. The Hutton Inquiry heard in 2004 that senior members in Defence Intelligence had set down their objection to the 45-minute claim in writing, saying it had been “over-egged” and was “far too strong” in presentation. Richard Dearlove, the MI6 chief, said there had been a misunderstanding: the claim related to possible battlefield WMD rather than long-range strikes.

The Chilcot Inquiry in 2011 heard Major General Michael Laurie, from Defence Intelligence, say: “The purpose of the dossier was precisely to make a case for war, rather than setting out the available intelligence, and that to make best out of sparse and inconclusive intelligence the wording was developed with care.”

The same year a memo, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, from Sir John Scarlett, the chairperson of the JIC, to Sir David Manning, chief foreign policy adviser to Blair, showed how information was manipulated to put Iraq in the dock.

An early draft of the dossier had stated that four countries – Iran, Iraq, Libya and North Korea – had “WMD programmes of concern”. Jack Straw, the foreign secretary, pointed out the document had to show that there was “an exceptional threat from Iraq”. Sir John suggested, in response, the dossier should only focus on Iraq as “this would have the benefit of obscuring the fact that in terms of WMD Iraq is not that exceptional”.

Any attempt to challenge the WMD allegations was met with fierce “rapid rebuttal” by Downing Street. During the Hutton Inquiry, an email was unearthed written by Straw’s then private secretary, which described the then foreign secretary’s role in “hardening up” the dossier with a “killer paragraph”.

A memorandum copied to Alastair Campbell and John Scarlett revealed that Straw said “The first bullet of para 6 the importance of weapons of mass destruction should be strengthened to explain the centrality of WMD to Saddam Hussein’s role – the projection of power etc.... Crucially the section should explain the role of the WMD in the political mythology which has sustained the regime.”

When The Independent found and published this memorandum at the time of the Hutton Inquiry, Straw’s reaction was to go on the attack, disputing that this showed he was trying to harden up the WMD “evidence” or that this added to the possibility of war.

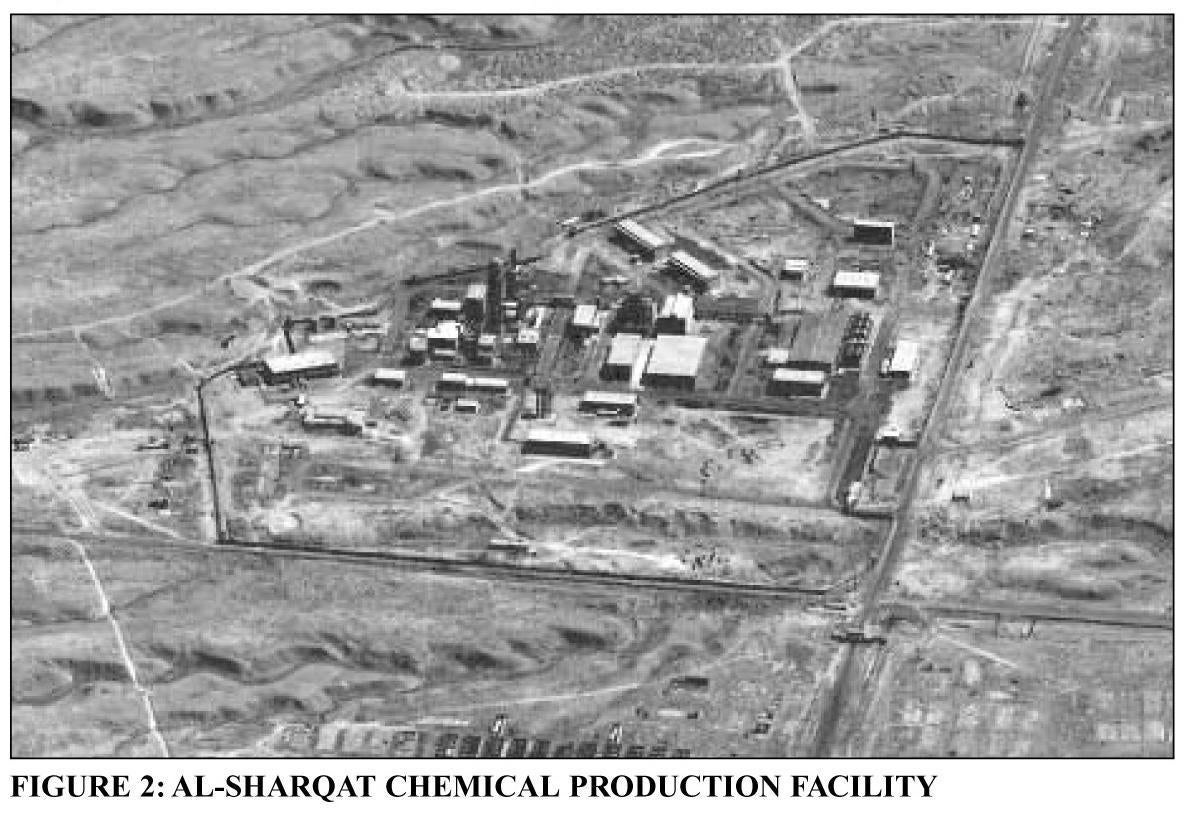

I had firsthand experience of how the government went on the attack when challenged. In September 2002 I was among a small group of journalists at the Al Rashid Hotel in Baghdad who downloaded the Iraq dossier from the internet. We had arranged with the office of Tariq Aziz, Iraq’s deputy prime minister, to visit some of the sites supposedly used by the regime to manufacture chemical and biological weapons mentioned in the document.

We chose the sites to visit and we were taken there by the Iraqi authorities within two hours of the dossier being produced. In our reports we said that we had seen nothing overtly suspicious during our visit, stressing, however, that we did not have scientific expertise. That, however, was enough for Downing Street spin doctors to accuse us of being “naive dupes” who had fallen for the regime’s lies. Our newspapers, they raged, were highly irresponsible for printing such “propaganda”.

Among the sites we visited was al-Qa’qa, a military complex 30 miles south of Baghdad. According to the dossier, al-Qa’qa had been dismantled by UN inspectors after the 1991 Gulf War but had since been rebuilt and was producing phosgene, used in nerve agents. We also went to Amariyah Sera vaccine plant at Abu Ghraib, a suburb of Baghdad, which had – again, according to the dossier – restarted its use of “storing biological agents, seed stocks and conducting biological warfare-associated genetic research”.

Both the sites were inspected soon afterwards by the UN teams in Iraq at the time. They found no presence of WMD. They were inspected again by the Iraq Survey Group after the invasion: they too failed to find any WMD – as was the case with every other site mentioned in the dossier.

On return visits to the UK, it was clear that invasion was inevitable. The inspections in Iraq were but shadowplay. What was also clear, talking to members of the British military, was their concern about the mission they were about to undertake. As the Bush and Blair administrations persisted with their charade of seeking a negotiated solution to the crisis, their military commanders were being delayed in starting the necessary preparations for war.

British service chiefs met, in particular to voice their concern about the legality of the war. Admiral Lord Boyce, the chief of defence staff, subsequently asked the government for a guarantee of this in writing. He told the Chilcott Inquiry in 2011: “I made it clear to the prime minister in January 2003 that I would require an assurance of the legal base of the conflict. This was reiterated more than once in the following weeks, and formally and explicitly in March once it became clear that it was probable that coalition forces would invade once political approval was obtained.” After pressure, Lord Boyce got a “one-liner” from the Attorney General, Lord Peter Goldsmith, confirming the war was legal.

After he retired, Lord Boyce told me: “I was repeatedly telling my American counterparts that the UK was not in the business of regime change in Iraq. They were convinced that’s what President Bush wanted and Tony Blair would follow suit. I didn’t realise at the time how thrilled Blair was because he thought he was close to Bush.”

Lord Boyce died in November last year. General Sir Mike Jackson, who had become chief of general staff (the head of the army), told me this week: “It was decided at the meeting of the service chiefs that we needed clarification about legality and we needed it in writing. We were prepared to fight for Queen and country but it had to be nailed down that the war about to take place was legal.

“The intelligence used in the run-up to the war turned out to be fool’s gold. I don’t think it was all just made up, but of course it turned out to be untrue. There were, as we know, a number of inquiries held afterwards, and certainly some very interesting things came out.”

When Gordon Brown’s government proposed in 2009 that the Chilcot Inquiry should be held in private, General Jackson and other senior military and intelligence officers stressed to The Independent at the time that the hearings must be public and transparent to have any credibility.

General Jackson said: “I would have no problem at all in giving my evidence in public, having proceedings be held in private would feed the climate of suspicion and scepticism about government, in fact there is no reason why witnesses should not give evidence under oath. The main problem with a secret inquiry in the current climate of suspicion and scepticism about Iraq is that people would think there is something to hide.”

Air Marshal Sir John Walker, the former head of Defence Intelligence, said: “There is only one reason it’s being that the inquiry is heard in private – and that is to protect past and present members of this government. There are 179 reasons [the number of members of British forces killed in Iraq] why the military want the truth to be out on what happened over Iraq. We have worrying questions about how intelligence was ramped up to suit Tony Blair and his cronies and their reasoning for invasion.”

Major General Julian Thompson, former commandant general of the Royal Marines, said: “We are looking at something extremely serious: the allegation that a British government manipulated intelligence to take part in an illegal war. What happened in Iraq cannot be hidden away, there is a need to examine what went wrong and look at the consequences.”

In America, Colin Powell later acknowledged that his address at the UN about uranium was a pivotal point in paving the way for the invasion, and what he claimed was wrong. He said: “It has blotted my record, but you know, there’s nothing I can do to change that blot... I’m the one who made the biggest presentation of it, and so it all sort of fell on me. I was more than embarrassed when the WMD was not found. I was mortified.”

Tony Blair has always insisted that he did not mislead the country. “What I cannot and will not do is say we took the wrong decision ... there were no lies, there was no deceit”, he said after the Chilcot Inquiry. Blair insisted in a recent BBC interview “I tried right until the last moment to avoid military action”: this is a claim his critics on Iraq find risible. He also maintained that it was necessary to join in the invasion to maintain the “special relationship” with the US.

“When I was prime minister, there was no doubt, either under President Clinton or President Bush, who the American president picked up the phone to first. It was the British prime minister. Today we’re out of Europe and would Joe Biden pick up the phone to Rishi Sunak first? I’m not sure,” he said.

George W Bush wrote in his memoir: “No one was more shocked and angry than I was that we didn’t find the weapons. I had a sickening feeling every time I thought about it, I still do.”

Two months ago, in a talk at the presidential library in Dallas about the Ukraine war, the former US president said: “The absence of checks and balances led to the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq; I mean, I mean Ukraine.”

It was not exactly a confession: but it told those of us who knew the invasion of Iraq was predicated on a lie all we needed to know.